So you want to buy a Triple-M Car Part 4 – The Magnas and Magnettes

By Philip Bayne-Powell

N-type

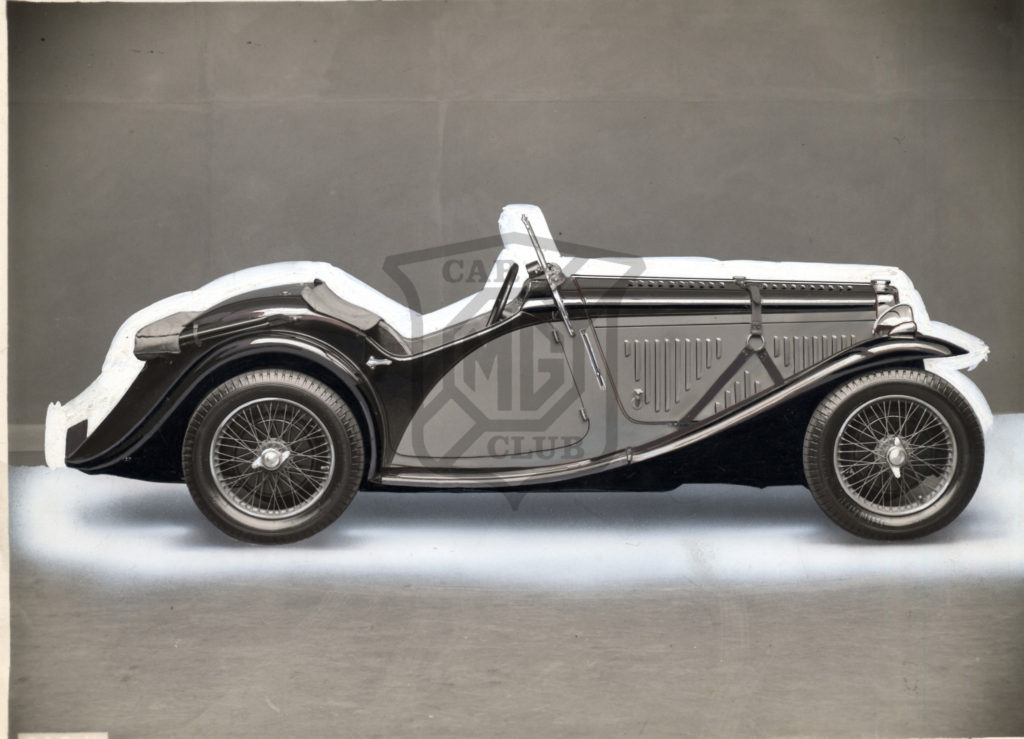

This was introduced in 1934, and took over from the L-type and the K-type, although the KN Pillarless saloon continued. Here was the flowering of the Triple-M design, with a new robust chassis onto which the body was rubber mounted. With a 1286cc engine producing 56 bhp, and a weight of just over 18 hundredweight, it had a good turn of speed. Although it had an engine bigger than the L-type Magna, it was for some reason called a Magnette. Bodies were 2 and 4-seaters, costing £305 and £335 respectively. A 2/4 seater (now usually called the Allingham after its designer) and a streamlined saloon (called the Airline) were also offered; the prices for these were £360 and £385.

The open cars now had their petrol tanks hidden away inside the sloping tail, although the spare wheel was still mounted on the outside at the rear. In a change to the designations used before, all N-type bodies were just called N-type (so there were no N1s, N2s or even N3s!). In 1936 the cars were improved and called NBs, after which the early cars were retrospectively called NAs. There was also a 2-seater ND, which used up some unsold slab tank K2 bodies, and this was generally used for competition work; only 24 of these were built. As superchargers were banned for racing in events for sports cars in the 1934 season, the MG works had to come up with an unblown racing car.

After the ND was found not to comply with the regulations, seven pointed tail car cars were quickly built for the Ulster TT and designated NEs. These proceeded to repeat the K3 result of 1933 by winning again. A road test of a 2-seater achieved over 80mph, which is pretty respectable for an 11/4 litre engine. Interestingly the L-type Continental Coupe was still being advertised in the N-type brochure of October 1934. Many N-types were used in trials; a works-sponsored “Three Musketeer” team of 3 specials using blown N-type engines in L-type chassis were very successful, complementing the “Cream Cracker” P-types. An N-type almost won the Monte Carlo Rally outright in 1935.

Chassis

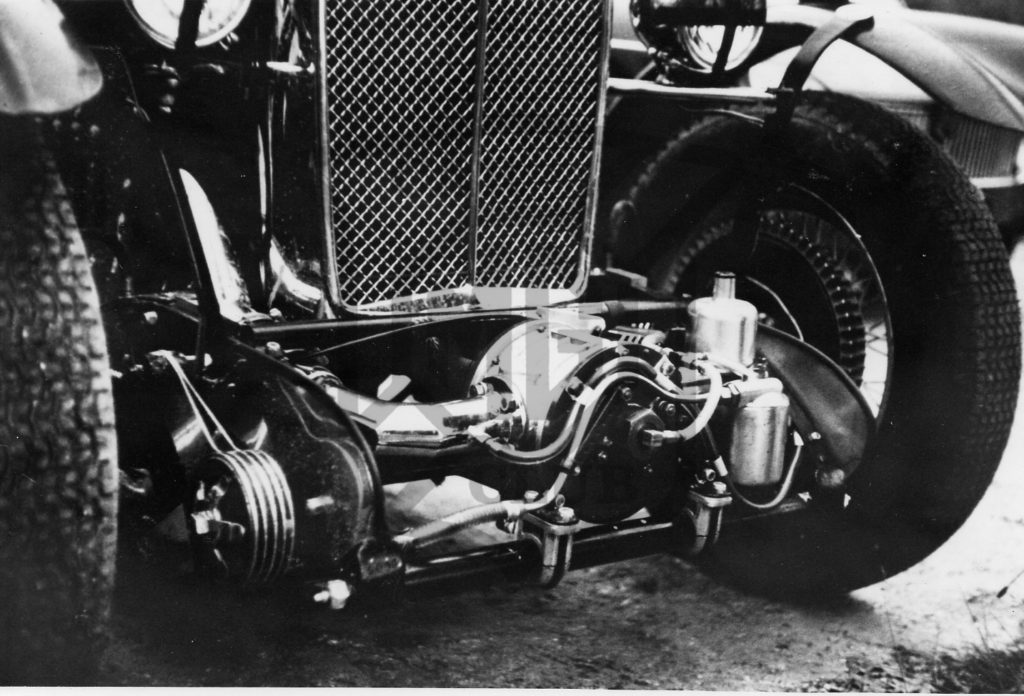

This was a new chassis with an increased track over the L-type at 3ft 9ins, and a wheelbase of 8 foot. It was not parallel as all chassis were before, but tapered outwards towards the rear. The springs were also wider, and more substantial, whilst the 12” brakes were carried over from the L-type. The centralised chassis lubrication of the L-type was also retained. The body was supported by rubber mounted channels outboard of the main chassis rails, and at the rear a timber cross bearer was also rubber mounted.

This gives a comfortable ride, and these cars are ideal for long distance motoring. (We have taken our N-types to France, Switzerland, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain and the United States). The steering was now by a Bishop Cam box, which is better than the earlier Marles Weller unit. For the first time the diameter of the wheels were changed to 18”. The propshafts on the later cars were fitted with Hardy Spicer needle roller universal joints, which were an improvement on the earlier plain bearing units, which suffered from poor oiling feed.

A new change was the adoption of Luvax hydraulic shock absorbers at the rear instead of the friction Hartfords used on previous models. The only problem with these is that they are not really suitable for the high frequency road springing used on these cars, and if they are too tightly adjusted, the casings split with the pressure, and tightness can also crack the chassis at the 3-bolt mounting.

Engine

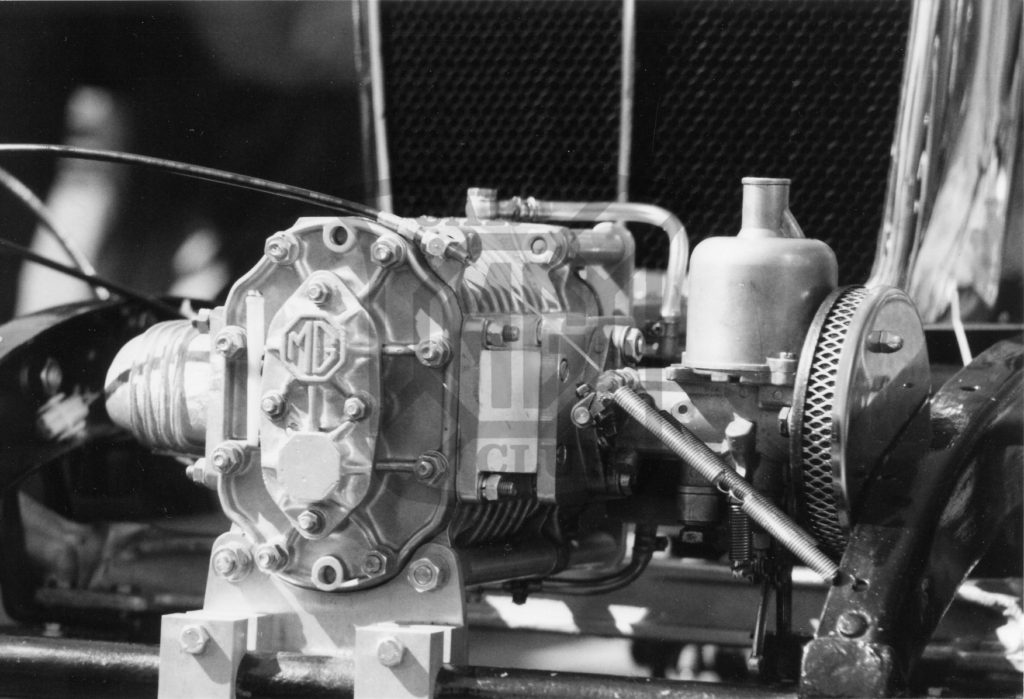

This was a development of the KD and L-type engines, and produced a healthy 56bhp giving a higher specific power than any other pre-war unsupercharged engine in standard tune. The carburettors were fitted further apart, after some testing by the works on the L-type set up, which gave better breathing. The rocker cover had an inbuilt oil filler, instead of the blockside oil fillers before, which made topping up the oil a lot easier. The oil filter and water pump was carried over too. These engines are very strong and can take up to 12psi supercharging without any modifications.

Oil pressure of 80-100psi indicates a healthy engine; if it is low it may well mean a worn oil pump, which can be easily improved by fitting new gears, as well as removing any grooves in the cover plate, by facing up on a piece of glass. If more power is being sought, some people will fit Carrillo or Cosworth rods with shell bearings, in which case a modern full flow oil filter needs to be fitted, either in the original Tecalemit unit, or else in line. Polishing and gas flowing of the cylinder head is also beneficial, and produces low down torque from 2000rpm or less, as well as breathing better at the top end of the rev range, which is around 5500-6000rpm for normal use.

Gearbox

This was the same as fitted to the new P-type and similar to the L-type, but was now just a single plate design. This is pretty strong, and can take a lot of abuse from first-timers trying to master double declutching, which is still required as there is no synchromesh. There is a nice cast aluminium remote control for the gear level, which incorporates a neat bracket for the choke and slow running control rods.

The gear ratios were changed from the L-type, with a much lower 1st and 2nd gear, giving a large gap between 2nd and 3rd, which requires the engine to be revved quite hard, followed by a quick gear change. The NB went back to the better ratios of the L-type. Recently the later, close ratio, gear sets have been made up, and make the gearing so much better.

Back axle

This is specific to the N-type due to the 3ft 9” track, and has a flange for bolting to the springs, instead of the U-bolt fixing used before. Half shafts are also pure N-type being longer than the F- and L-types, but are readily available, but with more power available are more liable to break. The diff carrier was now in steel, and an 8/41 crown wheel and pinion fitted; an 8/39 cwp can be fitted, but needs the engine power to be increased to cope. If fitted to a standard car, it will stifle the performance.

Electrics

The headlights were changed to Lucas 150 units, which are still to be found at Autojumbles, but the side lights are specifically Triple-M octagonal ones, which were originally made of Mazac, which very poor metal. These originals corrode away and break up, and don’t take chroming very well, but new ones are available in cast brass, which also takes the chroming better. The dynamo was the same Rotax AT 174 used on the K-type, and can suffer the same breakage of the top casting. There is a trend now to fit 2-brush dynamo conversions to overcome the problems with dynamos.

These look very similar to the original; this requires a CVC control box to be fitted, or else the original fuse box/cut out can be neatly converted. The dash board was similar to the L-type but now in wood, and sported more switches, including those for the new trafficators which were mounted in the sides of the scuttle. These trafficators are very difficult, and expensive, to obtain in their original slim form, so people fit the later fatter units. Twin 6-volt batteries are fitted either side of the prop shaft at the rear in a special battery tray bolted to the chassis rails.

Body

The scuttle was made stiffer by boxing it in with the firewall, and incorporating a useful double lidded toolbox. The 2- and 4-seater NA bodies had the usual scuttle humps with a quite high windscreen, making them look a bit top heavy, however the NBs had lower scuttle humps. The rear hinged, “suicide doors”, as used on most of the previous models were retained, but changed for front hinged doors on the NBs, with long chromed external hinges. Two-tone colour schemes were popular with light and dark red, blue and green being offered.

The darker colour was used on the most of the body with the sides of the bonnet, scuttle and doors being in the lighter colour; the NBs reversed this with the lighter colour on top. The other 2-seater produced (but never advertised) was the slab-tanked ND, using up the left over K2 bodies, but with their own special running boards and rear wings, as well as a spare wheel carrier similar to the P-type. The Pillarless saloon was joined by a new closed car, in the shape of the beautiful Airline Coupe. This was designed by H.W.Allingham, and was built by Carbodies, who had hitherto built most of the works MG bodies.

It was built on a duodetic timber frame, reinforced in places of high stress with extra metal pieces, to keep the weight down. It was only a 2-seater with good luggage space behind the front bucket seats, and the roof flowed down into a slightly rounded tail. A sliding roof was usually fitted with little “windowlets”, which, like a sunroof, make you believe you are in an open car. The same body was also fitted to the P-type, but due to the narrower track of the P-type it looks a big heavy at the rear. Unfortunately only 6 of these bodies were put on the N-type chassis compared with 42 on the P-type. The other car offered by MGs was a 2/4 seater, also designed by Allingham, but built by Whittingham and Mitchell.

This had a tilting panel over the rear two seats, which could be closed to produce a 2-seater car. The spare wheel was mounted in the wing, which left the beautiful tail uncluttered. This too was a good looking car especially when painted in the two-tone paint scheme. Only 11 of these cars were produced, of which 4 remain, including that of my wife, which has been in the family for 40 years now and will be the last car to be sold (if ever we get that desperate!). Due to the decent power available, many other coachbuilders (48 in all) fitted out this chassis with their interpretations, including Abbey, Maltby, Bertelli for Cresta Motor Co, and an unknown maker of a Faux Cabriolet which the author has just finished restoring.

Prices

With a total of 734 cars made in the 3 years of production it was the second most popular 6-cylinder car after the F-type. As this was the last, and most developed, of the Triple-M cars, the N-type is always popular, being a competent road car for all conditions, with fewer shortcomings than the earlier cars. Market prices reflect this. The 2-seater cars do not seem to come up for sale very often (although roughly the same number of two and four seater cars were built), and are snapped up at around £35,000; the 4-seaters are around £30,000. There is not much price difference between the NAs and the NBs.

When it comes to the rare NDs, recent sales indicate a price of over £60,000. The 2/4-seater “Allingham” is also rare with only 4 left, and would fetch a similar price to the ND. As for the beautiful Airline Coupe, of which only two remain, an NB version, rebuilt after a disastrous fire, on non-original steel frame, recently fetched £190,000 in America!! The racing NEs very rarely come up for sale, but could probably command a £150,000 price tag. A few NE replicas have been made, and these would be around £60,000. Only occasionally do the coachbuilt cars come up for sale, and these could fetch £45,000-£50,000. As only one genuine “Musketeer” trials car remains, several replicas have been built, and could sell for around £50,000. Any car with a supercharger will be £5-10,000 more than the unblown car, as this improves the performance quite measurably.

Basket case or fully restored?

When you consider how much it costs to restore a car properly, it would appear to make better sense to buy a car that has already been restored, where someone else has had to spend all the money. Very rarely can one recover the cost of a restoration if one has to sell the car for whatever reason (historic cars probably being the only exception). When you consider that it costs £1,500-£2,000 per cylinder to properly rebuild the engine alone, you will see that it costs a lot to restore the car yourself, even if you can do much of the expensive items like respraying, upholstery and hood yourself.

If you get the car professionally restored, you are even less likely to be able to recover your costs. The cost of Triple-M parts is more than T-type parts, and considerably more than MGB parts, even though nearly everything is now available. A certain copy of a Q-type has recently been produced with nearly all new parts except for the front and back axles, and the pre-selector gearbox!

When buying a restored car, you need to establish exactly what has been done, and by whom, to satisfy yourself that it is not going to let you down; talk to other Triple-M owners to find out who does good work, and who might not. I myself bought a restored car which had had £10,000 spent on the engine alone by a Ferrari/Aston garage, only to have the bottom end fail due to overlong replacement crankshaft oil plugs. Also the other thing to remember when buying a recently restored car is that its gremlins haven’t yet been fully sorted, while a car that has been restored, but then used on the road for a few years, should have most of these sorted out.

Sometimes a person starts off with all good intention of restoring the car properly, only to run out of money or enthusiasm half way through, and then take short cuts to quickly finish the car to sell and get some money back. These can give you a lot of grief, as you gradually find out where the short cuts have been taken, and then have to put things right. Sometimes these short cuts can actually damage the engine, or other bits of the car, meaning you will have to dig deep into your pocket again. If you can get a car that is part way through a restoration, you will probably get a bargain.

If you buy a wreck or unrestored car, you know what you have bought, as everything will need to be renovated, and you can also check what parts are missing, and if expensive to acquire (such as the original instruments), you can use this to beat the price down. The advantage of buying a “barn find” is that it will initially be cheaper to acquire than buying a fully restored car, and the cost of the restoration can be spread over however many years it takes to complete the restoration.

In addition you have the pleasure of restoring the car yourself and doing all the alterations and improvements you would like to do. There is also the joy of the first firing up of the car that you yourself have restored. However a restoration project is a long term commitment, and quite a few people fall by the wayside. You need to constantly keep in mind the pleasure to come of driving the “box of bits” that you have restored, and the joy of being able to tell people that it was your own work.

Supercharging

This is something that is pretty common in the Triple-M world, both originally and currently. Supercharging is a good way of boosting the power output of a car without too much of a downside. It will give a much wider power range from as low as 2000rpm right round to more than 7000rpm for racing. Supercharging started with the EX 120 record breaker, using a Powerplus blower, which was an eccentric vane type. A No. 7 or 8 Powerplus was used on the C-types and J4s, while the K3 used a No 8 or 9 Powerplus.

These were lubricated by an oil feed from the cylinder head, which was related to engine speed, often causing plugs to oil up as in the 1933 Mille Miglia. Later racing cars such as the Q and R-types used the Zoller supercharger, which had a tendency to wear quite rapidly so that the power output at the end of a race was considerably less than at the start; each Zoller blower was overhauled or replaced after each race. Marshall, a Roots type blower, was often used but these are not so efficient as the eccentric vane blowers at high revs.

As well as these works blown cars, there were firms advertising bolt-on blower kits using a Centric or Marshall blower, which were side mounted under the bonnet. These became quite popular for fitting to Triple-M cars in the following decades, often mounted alternatively at the front of the car, driven by a quill shaft as used by the works for their blower drives. This installation allows longitudinal and rotational movement to occur between the engine and the blower without transmitting these loads to the blower itself. The side mounted blowers were always belt driven off a pulley or double pulleys on the front of the crankshaft.

In the late 1930s there was an improved eccentric vane blower sold by Arnott, which was better built, and after the war this was developed by Chris Shorrock and was called after him. In the last few years people have been using the Volumex blower produced by Lancia for their Beta. This is similar to the pre-war eccentric vane blower and more reliable, and is also accepted by the VSCC. However these are now drying up, as Lancia are not producing these any more. New Marshall blowers are currently being built, based on the cabin blowers of old, and occasionally Centric parts are cast up to produce new blowers.

Many people like to put the blower out the front of the engine, and these require a long transfer pipe to get the compressed mixture into the head. A Kigass pump (mounted on the dashboard) was fitted to the works racers to inject neat fuel into the inlet manifold to ensure the engine started, and this is often reproduced today. The inlet manifold is quite critical, as if the mixture is fed into the front of the manifold, the rear cylinders get starved of fuel, so Robin Jackson of Brooklands developed a manifold that solved this problem. The mixture from the blower is fed centrally into a primary transverse manifold, and from there it was connected to a second transverse manifold by two equally spaced pipes, and then finally from the second manifold via four (or six pipes for the 6-cylinder cars) to the inlet ducts in the head. This ensures equal fuel mixture distribution to all cylinders and is pretty much the normal installation for track cars.

Supercharging the later cars is no problem, as the bottom end was designed for this eventuality, but putting a blower on the early two-bearing crankshaft of an M, D, or J-type requires a new stronger counterbalanced crank to be fitted with 15/8” diameter main journals, otherwise there is a real risk of you ending up with a broken crankshaft. These new cranks are readily available at around £1,100.

Replicas, Fakes and Copies

As Triple-M cars are now getting quite valuable compared with other cars, people are making up replicas of historic cars, initially for their own enjoyment, as a cheaper alternative to buying the “real McCoy”. This is made considerably easier due to the fact that the works made up their competition cars from parts already in production for the road cars. However there are some people who build up cars purporting to be the real thing, sometimes with a spurious history, and even the correct log book. In the past this was easier to obtain than it is now, when the car has to be thoroughly vetted before a duplicate log book is issued by DVLA. The Triple-M Register keep a close eye on these cars, and a call to our Registrar will reveal all the information we have, to enable any potential purchaser to decide on the provenance for himself.

The factory produced an M-type 12/12 Replica themselves after the success of their cars at Brooklands. This was a works catalogued model, but many modern replicas have been built of these and the works 12/12 cars from the basic standard M-type. C-types are often reproduced on a D-type or J-type chassis, whilst a J4 replica can be easily produced from a standard J2, by fitting a doorless body and a front mounted supercharger. Many K3 replicas have been made using a shortened K1 or KN chassis, or even a brand new chassis, which is available these days.

A few NE replicas have been built by fitting a narrow pointed tail body on an N-type, but the correct side draught SU carburettors and manifold are difficult to reproduce. Quite a few road going Q-type replicas have been made, as most people seem to want a car that can also be used on the road. The correct chassis for a Q-type is an altered K3 chassis; some cars have been built on a P-type chassis, but this is too short, or an L-type chassis, which is longer. No R-type replicas have been built (yet!) due to their unique independent suspension.

Recently an almost completely new Q-type copy has been produced from all new parts. This shows that the spares available are pretty extensive, but does tend to muddy the waters, especially if it acquires some spurious history over the years. A replica of the EX 120 record breaker was produced some time ago for the racing enjoyment of the builder, but after two or three owners it suddenly became the real thing and was about to be auctioned, when the original builder stepped in to correct the fraud.

A useful yardstick that used to be applied was that if the car possessed three out of the five major items (chassis, engine, body, gearbox, and back axle) with the chassis being one of the three, it could be considered to be the original car. This seems to have been relaxed lately, so that some cars have only a tenuous connection to the one that left the factory. I believe this to be a sad turn of events.

Recently the Register has brought in a nomenclature for replacement chassis of cars that have been crashed, which usually means the racing models. It was easier and quicker for the works to pick out a new chassis from the store rather than repair the original; these were generally stamped by the MG Car Co with the same chassis number as the original. At some time later the bent chassis got sold off and used in another project, meaning there are two chassis with the same works stamped chassis number running around. They are both MG chassis and so are genuine. Many replacement chassis also left the factory unstamped which further confuses the history.

Further Reading

Maintaining the Breed – John Thornley

The Magic of the Marque – Mike Allison

The Magic of MG – Mike Allison

The Works MGs – Mike Allison

MG Sports Cars _ Malcolm Green

MG Road Cars Vol.1 – 4-cylinder cars – Malcolm Green

MG Road Cars Vol. 2 – 6-cylinder cars – Malcolm Green

The MG Collection – Richard Monk

The Story of the MG Sports Car – Wilson McComb

Dream Machines – Ian Penberthy

MG Sports Cars – Autocar

Combat – Barré Lyndon

Circuit Dust – Barré Lyndon

A Practical Guide to the Restoration of the J-type – Graham Howell

MG Car Club

MG Car Club