So you want to buy a Triple-M car – Part 1 – The Midgets

By Philip Bayne-Powell

Many people are interested in the overhead cam Triple-M cars, but are put off actually buying one by the supposed complexity of the engine. Most people know that Triple-M stands for Midget, Magna and Magnette, the names given to the 4-cylinder (Midget) and 6-cylinder (Magna & Magnette) cars. These cars put MGs on the map in the 1930s, with their succession of race and record breaking exploits.

MGs produced some of the most powerful cars for their size in their day, with the Q-type producing over 150bhp/litre. MG engines were very advanced, revving up to 6,000rpm (and above on the racing cars), on a long stroke engine, which was pretty revolutionary then, when most cars were slow revving.

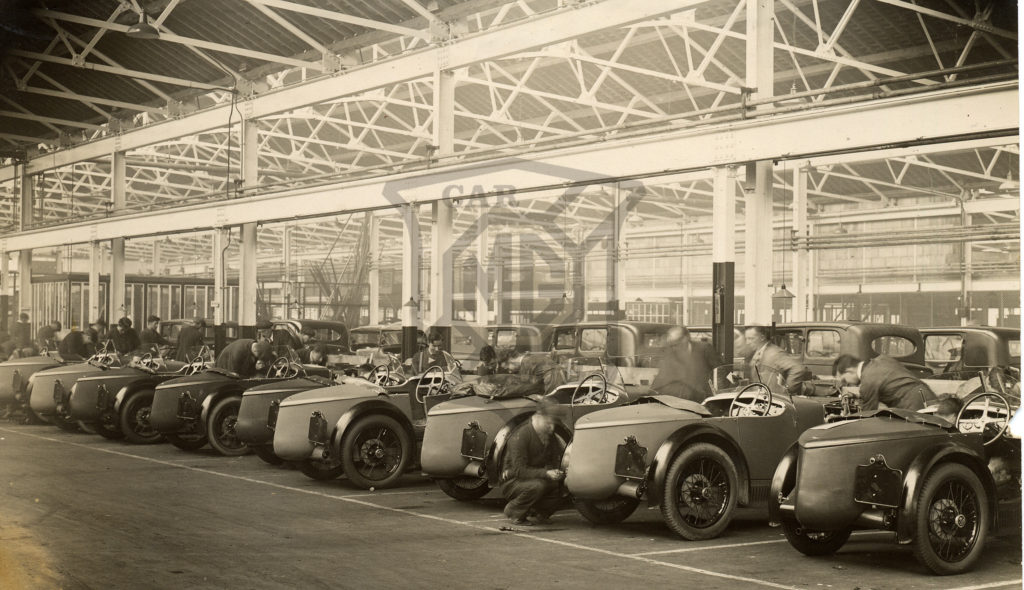

A lot of people are confused by the many variations of models, which were constantly changing from year to year. This was largely because the MG Car Co were constantly improving the models as a result of their extensive competition programme. Eleven different models were produced in the short time of seven years, from 1929 to 1936. Compare this with the T-type, which had only five different models in nineteen years.

The principal advantage of this constant update, is that the models only differed in probably one or two aspects from the previous model. This results in a lot of interchangeable parts, and means that spares are not too difficult to obtain, as it is worthwhile the suppliers reproducing parts which can fit several different models.

The subdivision of models is very confusing and not entirely logical, but generally a number 1 suffix (e.g. J1, F1, L1, K1) indicated a 4-seater body (open or closed), while the number 2 suffix showed it to be a 2-seater (e.g J2, F2, L2, K2 etc). A number 3 or 4 suffix indicated a racing car (e.g. J3/4, K3). For some reason when the P- and N-types came out in 1934, these designations were dropped.

So there were P-type and N-type 2- and 4-seaters. In 1936, revised P- and N-types were called PBs and NBs. Unless you are a masochist, try not to understand the K-type designations (with K1, K2, K3 bodies and KA, KB, KD engines fitted!!) However, given time, even these can be sorted into some sort of logic

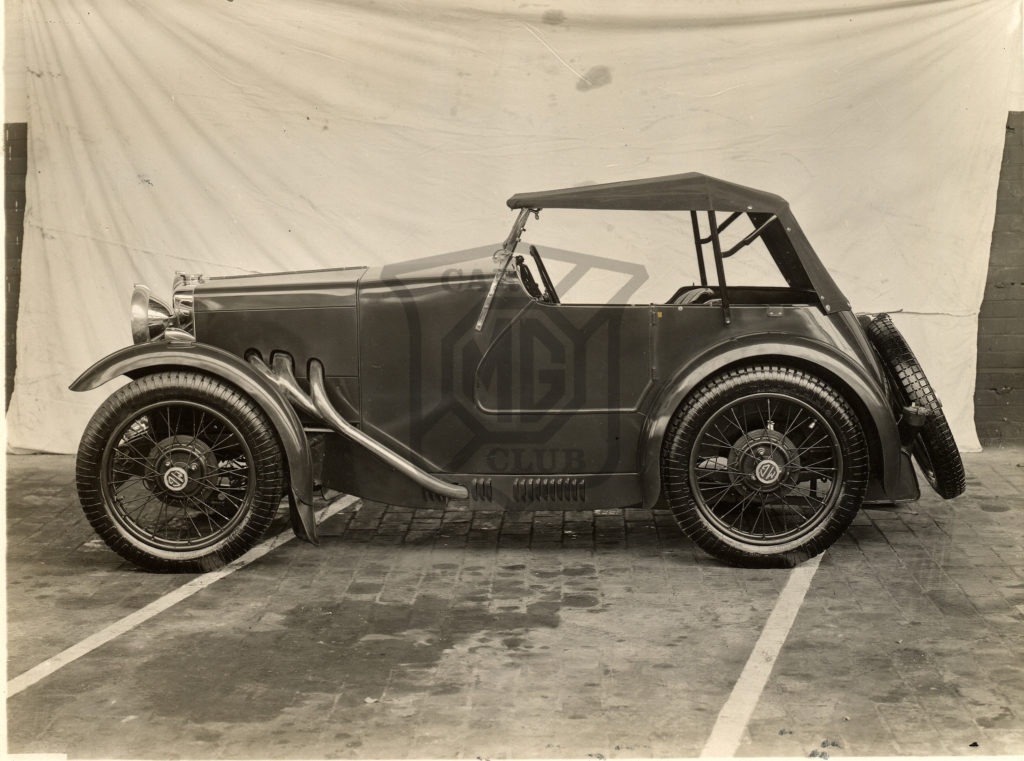

The MG body style of cycle/swept wings, with the spare wheel and petrol tank tacked onto the back, brought in with the J2 Midget in 1932, was the one that became established as representing the archetypal sports car. This was copied in some form or other by different sports and not-so-sports car makers. It is therefore a bit surprising that the N-type Magnette, in 1934, reverted to the enclosed tank in a swept tail. MG brought back the classic 2-seater body style with the TA, in 1936, and it carried right through to the TF of 1954.

All bodies were made with a timber frame clad in steel or sometimes aluminium, and like all timber bodies the lower sections are subject to rot, especially the door cills and A and B posts in front of and behind the doors. The rear of the body is usually the better preserved portion. Note that bodies may not have the same dimensions for one model, so that a door from one P-type will not necessarily fit another P-type – they are known to vary by up to 11/2”. These bodies are designed to flex with the chassis, so new bodies need to be made that can accommodate this flexing.

All Triple-M cars feature a vertical mounted dynamo at the front of the engine, which drives the overhead camshaft via bevel gears. This used to give trouble with oil leaking down the front housing all over the dynamo, which suffered as a result. Modern replacement oil seals are now fitted that stop this happening. The three-brush dynamo is often a source of trouble, but more reliable two-brush dynamos are now being made which look very similar to the originals.

Early engines had a single carburettor, non-cross flow head, and combined inlet and exhaust one piece manifold. This results in good low down torque, but the revs run out at about 4,500. Cross flow heads and twin carburettors came in with the J2, while the 4-branch exhaust manifold came in with the 1934 P-type. This enabled engines to rev to 6,000rpm (and more on the racing cars), but it meant that there is not much grunt below 3,000 revs. So the revs have to be kept up and then the engine note will sound fabulous.

Early cars had only a two bearing crankshaft, which after 70 years is likely to break; however, new cranks are readily available and are counterbalanced into the bargain. The three bearing crank was introduced with the PA in 1934, and is a much sturdier unit. The oil system can be modified by fitting an modern oil filter within the existing filter, however, if an external in-line spin off oil filter is used, this ruins the vintage look of the engine, and is probably not that necessary on a low stressed engine running up to a maximum of 4,500rpm.

Coupled with a great engine, the Triple-M cars, after the M-type, had an excellent chassis, constructed of channel section main frames with tubular cross bracing, with sliding trunnions instead of spring hangers for the rear of the springs, which allowed these cars to corner as if on the proverbial rails. The handling is a real delight, and makes driving these cars such a pleasure; this produced a chassis that handled beautifully, as Nuvolari himself found out when he drove a K3 to win the 1933 Ulster TT, using what we now know as the four wheel drift.

The other feature on all Triple-M cars is their cable brakes, which were used even on the racing cars, so they must have been effective, despite Wolseley and others going over to Hydraulic brakes. Each wheel has its own cables which consists of an inner and outer cable, the outer cable being restrained between stop ends so that it doesn’t matter what the wheels do, the inner cable always has to take the same route as the outer, preventing any one wheel from locking up due to cable shortening.

All cables are wrapped round a chassis cross shaft, which is rotated by a rod from the foot pedal, pulling the cables round a pulley at each outer end. The handbrake also operates the same cross shaft, so that all wheels are locked when parked, but can be brought into use in emergencies for greater purchase on the brake cables, helping to stop the car quicker. When drums, shoes and linings were all new the road tests showed these cars capable of stopping from 30mph in 30 feet.

However when parts get worn the braking suffers; it is made worse when brake drums are erroneously skimmed, as this changes the radius, which therefore no longer matches the radius of the brake shoes, which therefore do not make contact for the full area, until the linings wear to shape. Keeping the brakes properly adjusted is an on-going maintenance item, and owners soon get to adjust their driving style to leave a greater gap from the car in front to give a greater stopping distance.

The gearboxes on Triple-M cars give very little trouble, starting with the Wolseley 3-speed box on the early cars through the ENV box on the F-type, to the Wolseley 4-speed unit of the later cars. All gearboxes were “crash” boxes without any synchromesh on the gears, so revs need to be carefully matched to ensure smooth gear changes. Double declutching is therefore very necessary, and takes some time to master, but is extremely satisfying when done right. It soon becomes second nature – even my wife and daughter can do it! “Heel and Toe” braking, while changing down, is also an art that needs to be mastered, as the engine braking adds to that from the cables.

Propshafts are also pretty reliable in spite of the M-type’s fabric coupling. The later propshafts all had universal joints, with the better needle roller joints coming in on the later cars. The intermediate propshafts, before the Hardy Spicer joint, had trouble with the greasers on the sliding universal joint, as it lubricates the sliding joint first before getting to lubricate the universal joint itself; therefore these need to be well greased up, even if the excess grease seeps out of the splines.

Back axles on the earlier cars were pretty reliable, as not much power was being transmitted, but as the power rose, halfshafts break and crown wheel and pinions break teeth, especially if the original engine output has been increased, or if the car is being used in competitions. Trialling these cars is a sure way to break diffs and half shafts!

Wheels are generally 48 spoke 2.50 x 19”9 (taking 4.00 or 4.50 x 19” tyres); the N-type had 2.50 x 18” wheels. These wheels are pretty strong on the smaller cars, but tend to break spokes on the heavier and competition models. “Butted” spokes, as originally fitted, are stronger, but more expensive; and some people have gone to 60 spoke wheels on N-types to overcome regular breaking of spokes.

When considering buying a Triple-M car, it is worth seeing what you get for your money, in terms of speed, handling, comfort, braking etc. The later cars were better than the earlier cars in nearly all respects, as the works developed the cars through the years. The N-types are comfortable long distance fast tourers, while the M-types were pretty basic, and not really suitable for long distances, which often appeals to some people. But all Triple-M cars are a joy to drive involving the driver in getting the best out of the car.

It is most important to get as much information on the model you are proposing to buy and so it is best to get in touch with the Triple-M Register, who will point you in the right direction; also the website www.triple-mregister.org is a must for getting information, as well as checking out the cars for sale adverts. If you are at a meeting go and speak to an owner of the model you are after, and they will be only too glad to bore you to death on the virtues of their model, but also quiz them on the problems too!

As with any MG you should really get to drive the car first. This is easily done if the car for sale is on the road; but before this, it is better to get a drive in a car that is well known as a good example of the model. This can then be used as a benchmark when driving a car that is for sale, and will show if that car has been properly put together. It will also allow you to haggle with the vendor on aspects that are not up to scratch. If the car you are considering buying is not a runner, it is even more important to drive a good example beforehand, so that you know what to expect when the car is restored.

I have set out the pros and cons of each model in the following section. I have not included the pure racing cars like the Q and R-types, but many of the competition cars like the C-type, K3 and J4 can be used without too much trouble on the road. I have owned nearly every model of Triple-M car in the last 45 years, except the J-type, so the following comments are largely from personal experience, not hearsay.

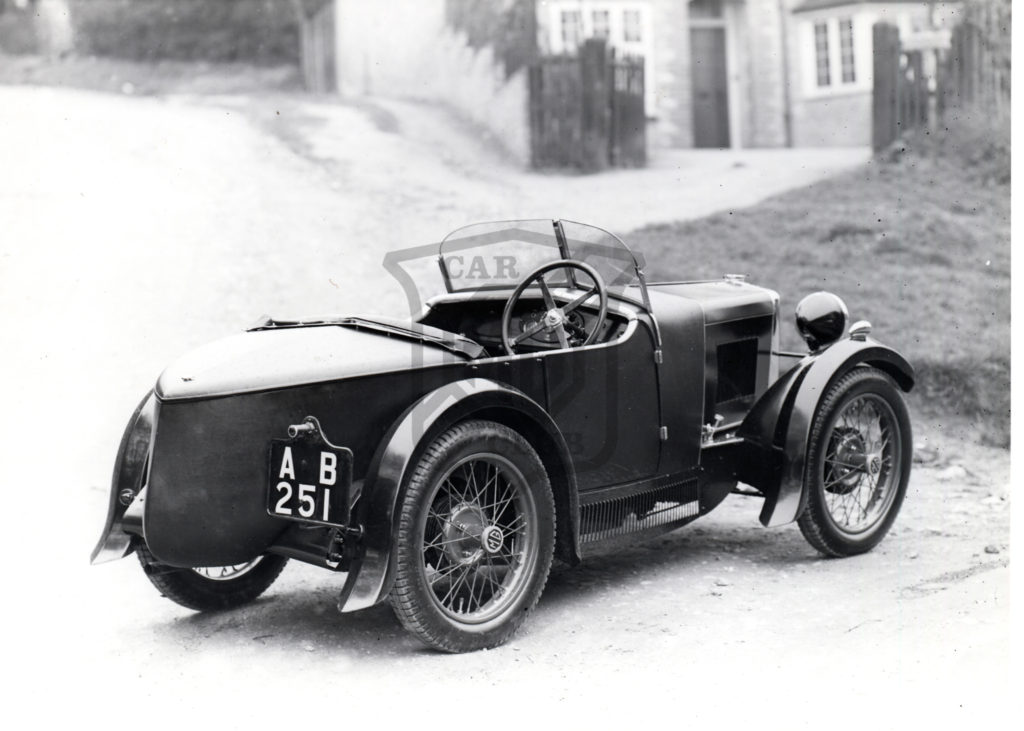

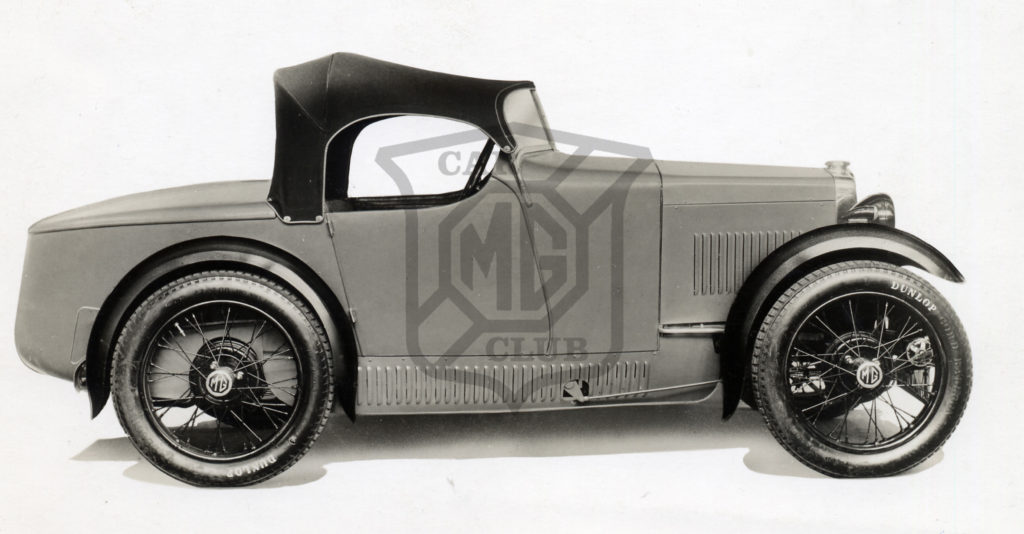

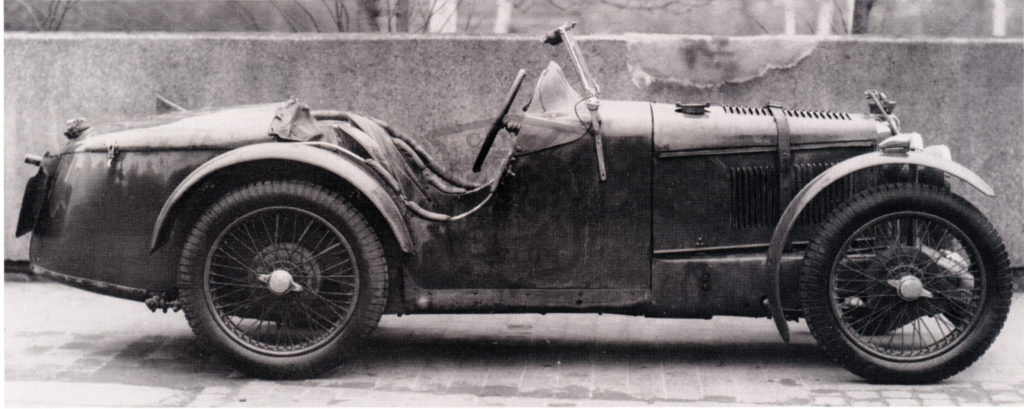

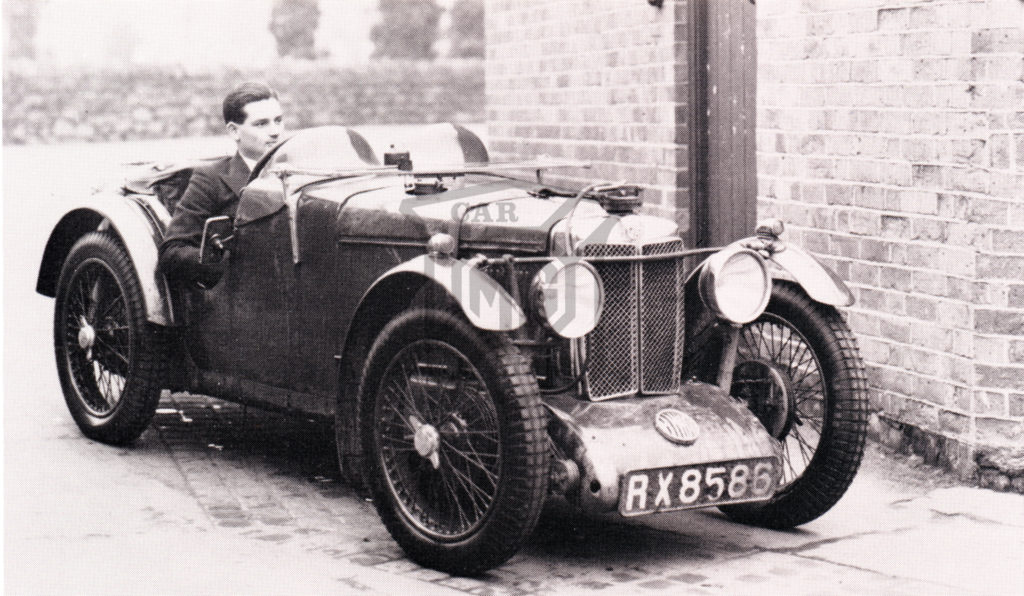

The M-type

This was the first Triple-M sports cars, and was essentially a development of the overhead cam Morris Minor. It was the Mini Cooper of its day, being based on a standard touring car. Initially it produced 20bhp, but the valve timing was altered on later cars to give 27bhp. This, coupled with a light weight of just over 10 cwts, produced a lively car. The engine gave good torque, but ran out of puff at about 4,500 revs. The 8” cable brakes were well up to the task of stopping this light car (I have locked up the brakes on our M-type in an emergency stop!).

The M-type is a great car to drive with very accurate steering from the Adamant box. However these are SMALL cars, with a wheelbase of only 6ft 6”, and a track of 3ft 6” which is the same for all the Midgets. The cockpit is therefore a tight squeeze (or impossible for large or tall drivers!). The erected hood is virtually useless as it restricts the driving position, as well as the visibility, and it is difficult to get in the car with the hood up. Invest in a tonneau and some waterproofs!

Chassis

This is a Morris chassis with an MG chassis number stamped on the front right hand chassis/spring knuckle; check that this number matches the log book and the plate, which is fitted to the bulkhead. Chassis have been known to be swopped over in the past, and unfortunately new plates are produced with any chassis number you wish, further adding to confusion.

The channel section chassis runs over the axles, and the springs are pivoted at the fronts and supported by shackles at the backs.

The 8” brakes are steel Morris drums with shrunk on aluminium cooling fins; they are operated by cables wrapped round pulleys on a brake crosshaft, which is mounted behind the gearbox. Early cars had a combination of rods and cables, but it is best to fit the later all cable system. Early cars also had a hand brake which operated on the transmission, whereas later cars had the handbrake interlinked with the foot brake, so that the hand brake operates the main brake cables, and on all four wheels, something that is carried through for all later Triple-M cars.

The brake cam and pivot bearings in the backplates are also a weak point, as they often crack away from the backplate, which obviously affects the braking.

Wheels are the same as the Morris Minor, and the earlier ones had a small hub with protruding flanges to pick up the spokes, while the later ones had a larger hub with a stronger flatter flange, all held on with only three wheel nuts per wheel. They only had 36 spokes on the standard car, which is why later, more powerful, Triple-M cars went over to 48 spoke Rudge Whitworth knock on wheels.

The steering box is a lovely recirculating wheel Adamant unit, which is very precise when not badly worn; however due to the fact that it is a recirculating wheel, the latter can be moved round to a new, unworn, location and the drop arm refitted.

Engine

These Wolseley built engines were pure Morris Minor 4-cylinder, 847cc overhead cam units, which were breathed on by MGs. A single 1” SU carburettor feeds the non-crossflow head on the nearside, and a combined cast iron inlet/exhaust manifold deals with the gases. The small 57mm bore was used on nearly every subsequent Triple-M car. The early cars had camshafts with no overlap, and produced only 20 bhp; later cars had a revised camshaft with 7 degrees of overlap, giving 27bhp – a very useful 35% increase.

The dynamo is mounted vertically at the front of the engine on these cars, and drives the overhead camshaft through bevel gears; this system of the dynamo driving the overhead camshaft is generic for all Triple-M cars, and differentiates them from the later push rod T-types. Originally there was only a felt oil seal coupled with a thrower in the head where the vertical drive shaft sits above the dynamo. This required the works to set the dynamo exactly under this shaft to ensure the oil did not leak over the dynamo.

However this was not always carried out by garages overhauling these engines, with the result that Triple-M cars got a reputation for leaking oil all over their dynamos. Subsequently a lip oil seal was fitted in the vertical drive housing by Toulmins and Thomsons of Wimbledon. This was reasonably successful, but still required the dynamo to be set up close to vertical to allow the lip seal to accommodate any slight discrepancy.

This is achieved by shimming the front housing to get the fore and aft alignment, and by doweling the front housing to the front of the block to ensure the dynamo is vertical in the sideways alignment. This means that if you try to fit a different front housing to the block, the original dowel will probably be in the wrong position; this also applies if you have a new block, in which case the dowel hole has to be drilled. A tight fitting mandrel passed through the hole in the front of the head is required to check/adjust the dynamo alignment.

The cylinder head also needs to be located exactly over the centre of the front housing, and there are two head studs with wider bases which are fitted at diametrically opposite ends of the head to ensure the head is correctly located. Often these studs are missing or located in the wrong position, which allows the head to move off its correct position. I have elaborated this point at some length, as it is critical to all Triple-M cars.

The crankshafts on M-types have only two bearings, and an original 75 year old crank will now be well past its fatigue life. New counterbalanced stronger cranks are readily available, and once fitted give total peace of mind. So try and get a car with a new crank, or else beat the price down.

The oil filtration system is very primitive with a gauze filter in the sump, and a very coarse oil strainer fitted between the sump and pump, which can lead to air getting into the suction pipe if the connections are not 100%.

There is no water pump or fan on these M-type engines, which can suffer from overheating if they have been modified; removing the nearside bonnet side panel is often resorted to!!

After you have had the car for a time, the engine can be usefully upgraded with a later 12/12 camshaft, bigger inlet vales and carburettor, and later J-type rockers. This allows the engine to rev much more, without the loss of the low down torque. A standard M-type is good for about 50-55mph, but the better engine gives you 55-60mph, and quicker acceleration.

Gearbox

The 3-speed gearbox is a Morris unit and is bolted to the back of the engine, with a long wobbly gearstick sprouting out of the top, which initially requires a bit of hunting under the dashboard to find, but it soon comes to hand. The 3-speed gearbox limits the performance of these cars, as second gear is quite low, but it needs to be engaged on many hills, which then brings the car’s speed down to an embarrassing crawl.

If possible, get a car with the 4-speed gearbox conversion, which was fitted to Morris cars (or a later J-type gearbox which fits); this allows the revs to be kept up on most hills, and also can be used when slowing down for roundabouts or bendy roads/built up areas. It transforms the car. If you get a car with the 3-speed box, start looking round for a 4-speed version to be fitted after you have got used to the car- the propshaft needs to be shortened by 1” to accommodate the bigger box.

The propshaft originally had fabric universal joints, which can break up, causing severe vibrations, which is worrying if you do not know the reason. However new modern rubber based couplings are available, and do the job quite satisfactorily, although some people go to the expense of getting a propshaft made up with Hardy Spicer universal joints, but I do not consider this necessary.

Back axle

This is a riveted construction, and the wheel bearings and hub carriers are held on with a large castellated nut with a locking tab washer; these need to be tight to prevent slop of the bearing carrier. Oil is prevented from coming out of the ends of the back axle with oil seals slipped over the half shafts. These used to be made of cork but are now made of plastic. M-types do not seem to have trouble with leaking half shafts like the later models.

The hubs, which are a press fit onto the half shaft, are bolted on (with the brake drums) with only three wheel nuts. These wheel nuts are chrome plated brass; due to the softness of the brass, the threads can strip and the wheel then tries to come off, especially on the near side. Steel Morris nuts can be used, or else the new stainless nuts available from one of the Triple-M traders. Despite this, it is advisable to check the rear wheel nuts regularly.

Electrics

These were the same as the Morris at 6 volts, and consequently if the battery is not well charged can cause starting problems. However if you are driving at night the headlights are no use at all, even after changing to halogen bulbs I have found. There was no fuse box as such to protect the various systems (one was fitted on the Coupes), only a field fuse for the dynamo. It is therefore a good idea to install a hidden fuse box or in-line fuses to the wiring.

Body

The original bodies fitted to these cars were a timber framed, fabric covered boat tailed devices with a split V-windscreen, weighing about 2 hundredweight. The whole car weighed only just over ½ ton, which made them quite sprightly. The spare wheel was carried inside the tail, accessed via a lift up lid. The 6 gallon petrol tank was fitted under the scuttle and fed the carburettor by gravity.

A tap under the tank could turn off the fuel completely, or else be turned over to access the 1 gallon reserve, achieved by having different pipes going up inside the tank. This reserve petrol system was used on nearly all Triple-M cars, and ensured that when you filled up with petrol you automatically filled up the reserve, as it was in the same tank – a very simple device.

The fabric bodied cars gave way to steel panelled cars in 1931, and the original cycle wings changed to angular, helmet, wings, which I consider look much nicer.

As well as the open car, a closed 2+2 Coupe was offered. These are a delightful looking car, but with all the extra bodywork adding another hundredweight to the car, they struggle to perform.

As well as the normal road car, factory replicas of the racing 12/12 cars were offered for the sporting enthusiast. These had improved valve timing, different carb and an external exhaust; 21 of these were made. However many replicas of these factory Replicas have been produced in recent years, so take care when buying a 12/12 car and make sure it is not a recent fake.

In the three years of production 3,235 cars were produced; of these 530 were the closed Coupe. Also in this figure, 82 chassis were sold, presumably to the specialist coachbuilders. However only Jarvis of Wimbledon and University Motors are known to have produced their own variations, of which only a couple survive.

Prices

The advantage of the M-type, is that they are relatively inexpensive compared with the later Triple-M cars. Also in the three years of production, 3235 cars were produced, so there are a good number to choose from. Many of the parts are still Morris items, which helps keep the costs down. A good running car would set you back £8,000 or so. The 12/12 factory Replicas don’t often come on the market, but with their competition history would be over £20,000, whilst a modern reproduced 12/12 car would fetch around £15,000.

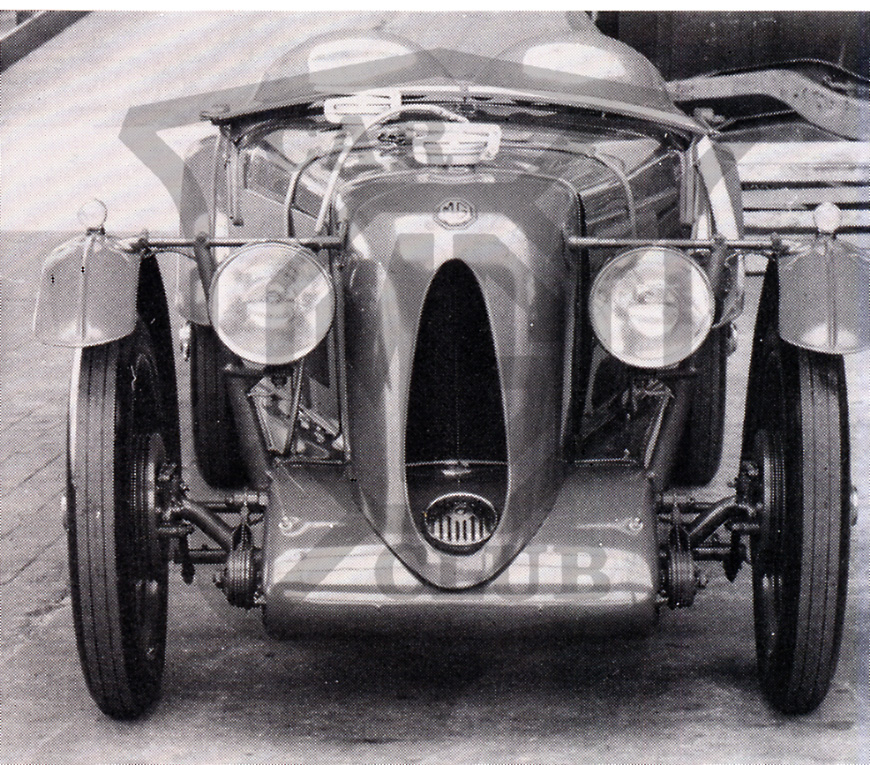

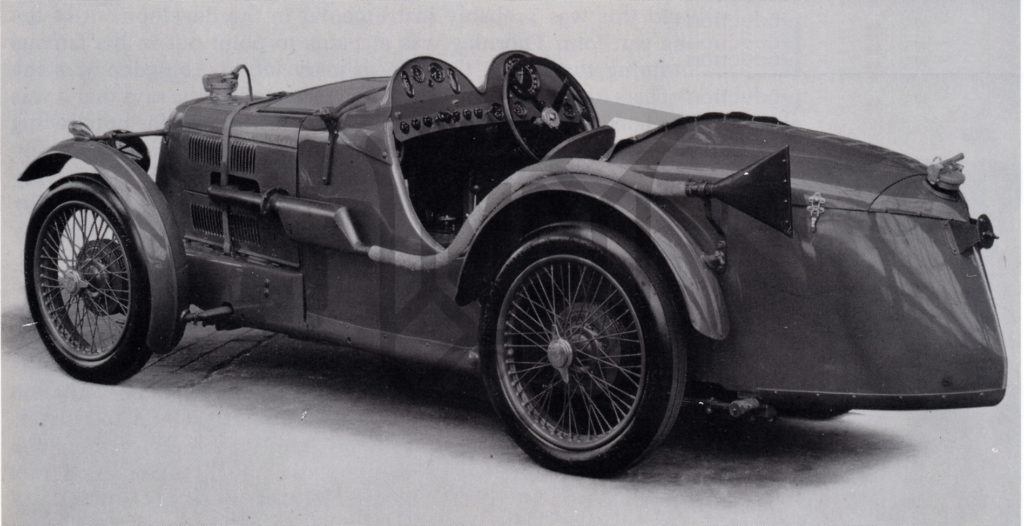

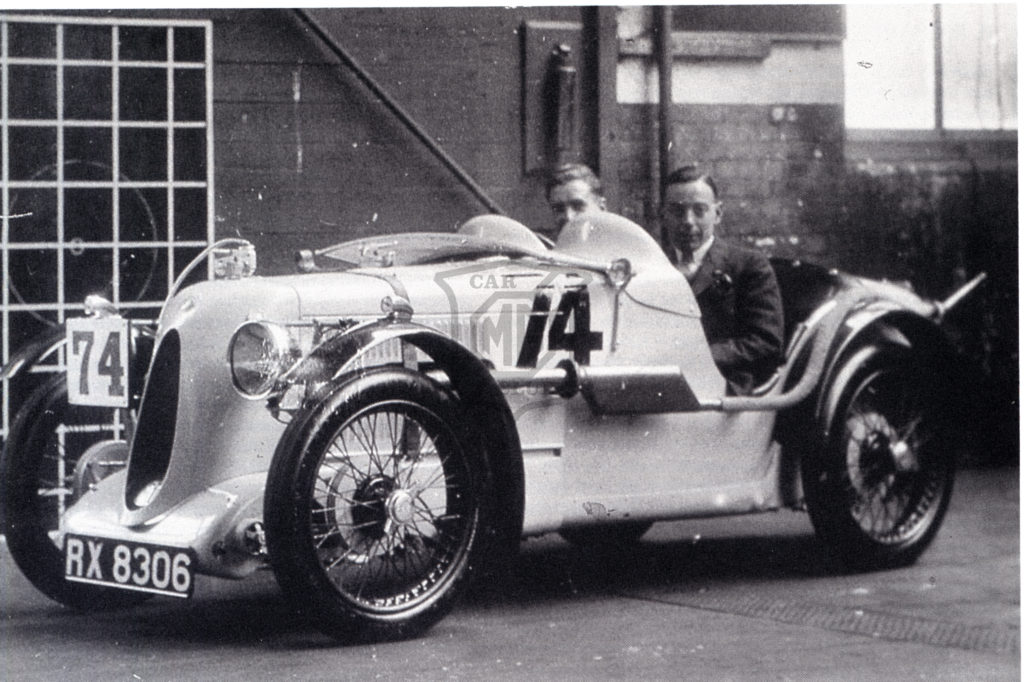

The C-type

This was the first model with the new underslung chassis, developed from the record breaking EX120, and incorporated the sliding trunnion rear support to the springs both front and back, which was carried through to the last of the Triple-M models. It came out in the middle of 1931, and was advertised as a road racing car, that was ready for immediate track use, as 14 brand new cars proved in that year’s Brooklands 12/12 Race, winning outright and netting the Team Prize. These cars clocked up many successes in the following years as they were kept up to date with cross flow heads and supercharging, until the J4 took over.

Chassis

This was a completely new channel section chassis, underslung at the rear, so the back axle was mounted on top of the springs, but still upswept over the front axle. The chassis was all bolted together, and all the bolts were drilled and split pinned, ready for the track. The track was still 3ft 6ins as before, but a new front and back axle were provided, being MG items still produced by Wolseley. The wheelbase was only 3” longer than the M-type at 6ft 9ins.

The major change was at the back of the springs; these were mounted in split phosphor bronze trunnions, which allowed the spring to slide and rotate as it deflected, but at the same time the sides of the spring were held in place, preventing the sideways movement endemic of a shackle system. This produces excellent handling characteristics, and it is noticeable than many T-type racers use the TA chassis, which still used sliding trunnions.

The 19” wheels were now 48 spoke Rudge Whitworth centre lock pattern, (which was to become the norm for all the later models), as opposed to the bolt-on wheels of the M-type. This of course was useful when racing. The brakes were initially 8” diameter, still cable operated from a cross shaft behind the gearbox, (as are all Triple-M cars). Later, cars were fitted with the new 12” brakes, as fitted to the later Midgets, as a result of which they stop very well.

The chassis lubrication was by grouped lubricators and connecting pipes.

The propshaft was now an improved unit, using Hardy Spicer universal joints, and was mounted above the floorboards. The Adamant steering box from the M-type was kept, and this is again a lovely precise unit, allowing the driver to place the car very accurately on the road and giving great confidence when driving fast.

The petrol tank was now mounted in the tail, with a huge 15 gallon triangular tank filling the bottom half of the pointed tail, provided with a protruding filler right at the back of the tail. These tanks were originally bolted to the chassis, but after some early problems with the tanks splitting due to the chassis flexing, the tanks were supported on a rubber mounted sub-frame, and secured by metal straps.

Engine

The engine was initially an improved M-type, non-crossflow, AA head producing 37bhp unblown and 45 bhp when blown, largely due to a new camshaft with much greater overlap than even the 12/12 M-type camshaft, and the use of a larger carburettor, despite a reduction in capacity to 750cc.

This represented a 60% increase on power over the M-type, and even with slightly increased same body weight, produced a very rapid car, which proceeded to do well in the racing world for at least the next two years. The cars were later fitted with a new design of cross flow, AB head, and these cars then produced 44bhp unblown and 53bhp blown, which improved speeds even further.

The engine was now mounted on a three-point arrangement to allow differential movement between the chassis and the engine, whilst keeping the radiator in unit with the engine. This was achieved by using a central tube mounting bolted to the front of the engine, bolted up to a chassis crosstube, but it also extended forward to provide a platform on which to mount the radiator. This meant that the engine and radiator were firmly connected together, and were not affected by any chassis flexing. The rear of the engine was bolted to the ENV gearbox, which had its own crosstube bolted to the chassis sides.

This became the first MG production car to feature a supercharger. This was mounted at the front of the car between the front dumb irons, and was driven by a splined quill shaft off the front of the engine, i.e. at engine speed. On the AA head this fed to an inverted carburettor manifold on the nearside, while on the AB heads the mixture was fed into a manifold on the offside.

An external exhaust was fitted on the nearside with the regulation Brooklands silencer and fish tail. An attempt at quietening the exhaust was done by fitting a perforated tube inside the Brooklands silencer, but I can vouch that after 100 miles you soon get a headache! Ear plugs or a flying helmet help to reduce the noise.

Gearbox

The gearbox was a new ENV 4-speed unit, which is a beautifully sweet piece of kit, giving lovely “knife-through-butter” changes. The gear change is different from most arrangements, in that top gear pushes forward. It also incorporates a crosstube, which acts as the rear mounting for the new three-point engine mounting system;

Back axle

This is a one piece unit with an 8/43 diff unit as standard, but many other ratios were available. Nowadays an 8/41 or even an 8/39 is fitted for non-track work. The wheel bearing were now held into a hub carrier with a large castellated nut. A lip oil is now usually fitted behind the bearing to control oil leaking from the back axle onto the brakes, but originally a top hat seal was fitted to the inner end of the arms of the axle.

Also to stiffen up the axle spacer tubes are recommended to be fitted between the front and back flanges of the diff housing, with long through bolts tightening up the housing. Normally the diff carrier is bolted to threaded holes in the axle at the front and a rear cover plate is similarly bolted to threaded holes in the rear flange of the housing. There are probably only 2 or 3 threads in the thickness of these flanges, which can easily get stripped or cross threaded.

Electrics

These were originally only 6 volt, but by now most C-types have been changed over to 12 volts, which involves a change of dynamo and starter, as well as the cutout. Headlights were the very nice 8” Rotax units, and originally a single rear lamp was centrally fitted above the number plate mounted on the pointed tail. Two rear lights are now required, so separate lamps are usually mounted off the rear wing stays.

Bodies

The bodies of these cars were very pretty, with a pointed tail, separate twin scuttle humps (bolted onto a flat scuttle) and an external exhaust. No doors were fitted, only cut down sides to allow access. The bonnet top is a one piece unit located on pegs front and back, while separate side panels are fitted with tubes at the bottom which side over fixing pins on the side valences, allowing these panels to be quickly removed.

Many of these cars lost their heavy pointed tails early on in favour of a slab tank, to help cut down the weight of the car for racing, but most cars have now been rebuilt with pointed tails. When raced, these cars were fitted with an aluminium shell body, with no internal framework, which made the overall weight of the car some 200lbs lighter.

Prices

Only 44 of these cars were made, so they are quite expensive to come by, and do not come up for sale very often. They are usually snapped up by the people close to these cars. A rough price guide is from £70,000 to over £100,000, dependent on the car’s competition history. Several fairly accurate replicas have been built using a D-type chassis as the basis, and these can fetch around £40,000.

It is essential to check if you are offered a supposedly genuine car, to ensure that is not a replica. The genuine cars have a rear trunnion nut that threads inside the rear crosstube, all other Triple-M cars have a bigger nut, which threads over the rear crosstube. This is very difficult to replicate; all other parts can be reproduced relatively easily.

Read part 2 to explore the D-Type, J-Type, P-Type MGs as well as the spares, originality and costs of these 4 cylinder Midgets.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club