Green Envy

By Martyn Morgan Jones. Photos: Gez Hughes

Power play

Until well into the 1950s, the legacies of war were dramatic and tangible. The UK was virtually bankrupt, there was unprecedented hardship, many families had been torn apart, major cities were blighted by war damage and would remain so for years. Even rationing was still a fact of life. Plus, there was the paucity of raw materials which would, quite literally, shape the automotive industry.

To replenish its war-depleted coffers, Britain urgently needed to re-establish itself as a global exporter. The phrase ‘Export or Die’, coined by Hans Juda, became the government’s edict to businesses, especially car manufacturers, with the supply of materials being umbilically-linked to the number of cars exported.

Playing both the survivalist and the patriotic cards, MG’s role in the export drive was significant, with many TCs finding homes abroad. Its replacement, the TD, similar in appearance but rather different under the skin, proved hugely popular. In 1952, approximately 11,000 TDs were produced. Almost 10,000 went to North America. Yet, a sea change was occurring. Consumers, particularly in North America, were demanding more style, greater reliability, bigger engines and more than a degree of technical merit.

In with the new

MG wasn’t blinkered to these changes. Indeed, and with the TD’s replacement in mind, the company had been finessing the design of UMG 400 (EX 172), the Enever-built and rebodied TD that George ‘Spud’ Phillips drove at Le Mans in 1951. A new project number, EX 175, had been allocated and a prototype was shown to BMC management in 1952. But MG’s plans were stymied. Undoubtedly driven by commercial logic, and probably safe in the knowledge that, in time, MG would likely be given the go-ahead, BMC rejected EX 175 and threw its corporate weight behind Donald Healey’s proposal for the Healey 100. As a stop-gap measure, MG launched the TF. A good car, albeit as ‘square-rigged’ as its competitors were now ‘streamlined’.

Consequently, faster and more stylish cars, including Standard-Triumph’s ‘100mph’ TR2 began stealing a march on MG. Things were fraught at Abingdon, complicated too. Whilst the prototype languished, Geoffrey Palmer, recently appointed as BMC’s Group Chassis and Body Designer, had penned an attractive Midget replacement. Thankfully, clever and temporising tactics by MG, and the sharp decline in sales, predominantly in North America, convinced BMC chief Leonard Lord that a new MG, one that had style as well as substance, was now needed. Fortunately, the Palmer/Cowley design was considered too advanced – and certainly wasn’t welcomed by MG’s hierarchy who never wanted to play second fiddle to Cowley. In June 1954, Lord gave Abingdon the go-ahead to develop the EX 175 project into a production car. The new designation was EX 182.

Fast forward

The result was the stunning and revolutionary MGA. Announced in September 1955, here was an MG that traded on traditional core values, such as craftsmanship and quality. Yet, crucially, it looked and felt as if it belonged to the 1950s. The styling, the polar opposite to its predecessor, was sublime. It could nudge 100mph too. The new MGA had not only grasped the export baton; it was well and truly sprinting with it. Sales were excellent.

Nevertheless, John Thornley, MG’s General Manager, and Syd Enever, MG’s Chief Designer (and considered to be the ‘Father’ of the MGA), weren’t content. They wanted to enhance the MGA’s already-good image by introducing a high-performance version – a halo model; one that could undercut Porsche (which held a large market share in North America with various iterations of its 356) – and also knock it off the racing podium. Cue Twin Cam.

Changes

Two prototype twin cam engines were trialled: Appleby’s Austin version and Palmer’s 1489cc ‘Morris’ unit. The Austin version was dismissed on grounds of poor performance and because it required an all-new cylinder block and bottom end. The Morris version, which Palmer (who’d since decamped to Vauxhall) had begun designing in March 1953 and was based around the recently-introduced B-series block, was chosen. Design detailing was undertaken by Eddie Maher and Jimmy Thompson in Coventry and the head was later re-worked to Harry Weslake’s specifications.

The B-series, as debuted in the Magnette, was productionised at 1489cc. However, in 1958, changes in Appendix J regulations now allowed for an up-to-1600cc class in motor sport. To be competitive, the Twin Cam had to be nearer that limit. Blocks (which also required many special machining operations to facilitate the twin cam conversion) were duly modified on a special line at Longbridge, to 1588cc, before being delivered to Morris Engines in Coventry for build-up.

The result was an engine that produced 108bhp at 6700rpm. It was quite an ingenious design too. Where the camshaft had resided in the pushrod engine, there was now a jackshaft which, in brief, running at half engine speed, drove the duplex timing chain, distributor, oil pump and rev counter. To cope with the increased revs, the connecting rods were stiffer and the crankshaft was forged from EN22 steel. To achieve the desired high compression, the pistons were pent-roofed. Fuelling was by twin SU HD6 carburettors. Other changes included a 13-pint, finned, aluminium-alloy sump, an oil cooler, and a revised radiator and header tank arrangement.

Because it could handle the power, the standard B-series gearbox was utilised (a close-ratio gear-set and lower final drive ratio were optional). Braking was taken care of by Dunlopten-and-three-quarter inch disc brakes all round. Save for the steering rack being mounted further forward (due to the engine being longer), the chassis remained largely standard.

The MGA Twin Cam, which actually ended up being a much more specialised project than BMC had originally approved, was launched in July 1958. Regrettably however, its much-vaunted engine wasn’t really ready for public consumption. Which helps explain why the ensuing problems were many – and various. Bob West, an acknowledged restorer of MGAs and Twin Cams, provides an insight. “It’s a lovely design, but little development was undertaken during the intervening years. It was also compromised by BMC’s desire to make the Twin Cam more of a production car and put it on general sale. Unfortunately, amongst the majority of buyers, there was a general lack of understanding. Many cars were treated unsympathetically. All sorts of problems manifested themselves.

“If the wrong octane fuel was used, carburettors adjusted lean, wrong spark plugs fitted, and the ignition timing set incorrectly or, worse still, a combination of all four, the engine would overheat and piston crowns would disintegrate. Due to poor quality control rings, oil consumption was horrendous. There were issues with the valve caps too. They hadn’t been case-hardened and valves would pull through. And, the tappet bucket design was too short, often causing ‘tipping’.

“In fairness, BMC worked hard to overcome these problems and the engine did become more reliable. Better rings, and then better pistons were fitted. For areas where premium grade fuel was not available, standard pistons were installed, dropping the compression ratio from 9.9:1 to 8.3:1 and the power by 8bhp. Plus, the caps were case-hardened, tappet buckets lengthened and their aluminium carriers iron-sleeved. Even a revised distributor was introduced.”

Tarnished

Nonetheless, as was the case with later British sports cars such as the Triumph Stag, the engine revisions arrived after the model had gained a reputation for being desperately unreliable.

Customer dissatisfaction and warranty claims had cost BMC dearly, but it was the negative feedback from the crucial North American market that led management to look at the bigger picture. In a move aimed squarely at damage limitation, BMC pulled the plug on the truculent Twin Cam in May 1960, after just 1,788 Roadsters and 323 Coupes had been produced.

Winning through

Nonetheless, the Twin Cam had its moments of glory – and is worthy of many accolades. Driven by John Gott, PRX 707, the first works Twin Cam to be officially entered into an international event finished fourth in class and 10th overall on the 1958 Liege-Rome-Liege Rally.

SRX 210, a very famous Twin Cam indeed, raced at Le Mans three times. In 1960, in the hands of Ted Lund and Colin Escott, it finished first in class and 12th overall. Bob West, who owned this car until 2005, remembers it fondly. “It was a fabulous car. Well-balanced, with great brakes. And the 1762cc engine, which gave nearly 140bhp on Webers, was a delight. So tractable too.”

It’s not just the works cars that won through either. There were numerous successes in the hands of works-supported drivers and gifted privateers. Former works driver Dick Jacobs ran identical Twin Cams (registered 1 MTW and 2 MTW) for Alan Foster and Tommy Bridger, with many great results to their credit.

Racing is the Twin Cam’s ‘raison d’être’ of course, and there are quite a few examples competing successfully, and reliably, today. “Over the years lots of development has been done,” continues Bob. “If built properly, using high-quality components, and set up correctly, the end result is a delightful engine – reliable too. And powerful. Race versions can produce from 160 to 200bhp. For extra strength, most utilise a modified five-bearing block and many have been converted to timing belts.”

Homage

MG Car Club member Mark Tossell bought his first MGA, a 1958 Roadster, in 1995 – and has been smitten ever since. “I’d been a MG fan for quite some time,” says Mark, smiling. “But when I first set eyes on an MGA, it was love at first sight. The lines are stunning. To me, it’s the best looking MG ever. The other great thing about the ‘A’ is it’s old enough to have a wonderfully classic charm, but can also keep up with modern traffic. It’s a glorious car.”

Mark, who’s renowned for his attention to detail and quality of workmanship, has restored and period-modified his 1958 Roadster, complete with a Judson Supercharger. Five years ago he also acquired a low-mileage, one-owner 1958 Coupe, although it’s since changed hands. “It was lovely,” admits Mark. “But, I’m more of a Roadster fan.”

As luck would have it, Mark found a Roadster, an unfinished project – a very interesting one in fact. “It was actually a 1959 Twin Cam,” he reveals. “A Twin Cam wasn’t really on my radar, but the more I thought about it, the more it appealed. I’d modified my red Roadster so it recalls the best fast road versions of the period. And I’d always loved the look of the works cars, especially those raced by Dick Jacobs, and 777 ENK too, which Bob West owns. I thought it would be nice to build mine to resemble a period race car.”

Having studied ex-works Twin Cams, and having undertaken extensive research, Mark began the build-up in 2013. “Everything has been refurbished or renewed, painted or powder-coated,” he impresses. “Not one thing, however small, even in places where it can’t be seen, has been overlooked. The brakes are genuine Twin Cam, including the master cylinders and reservoirs. So too are the peg-drive wheels. These were widened in period. Even the dampers are correct and in the proper colour. I lowered the car a touch though. It sits so nicely now.”

It certainly does. And looks so good too. Painted Ash Green, the same hue that adorned SRX 210 at Le Mans in 1959, and with the front valance insert painted a contrasting Old English White, it’s a visual feast. Devoid of any design fripperies or unnecessary embellishments, the shape simply flows. The interior is a delight too. “I’ve fitted a Derrington steering wheel,” mentions Mark. “And the ammeter and large rev counter are as per works cars. The seats are genuine Microcell and leather-covered. The valance insert and aluminium gearbox tunnel were made specially. The tunnel has been riveted as it would have been back in the day. The ‘Sports’ screen is from Bob West.”

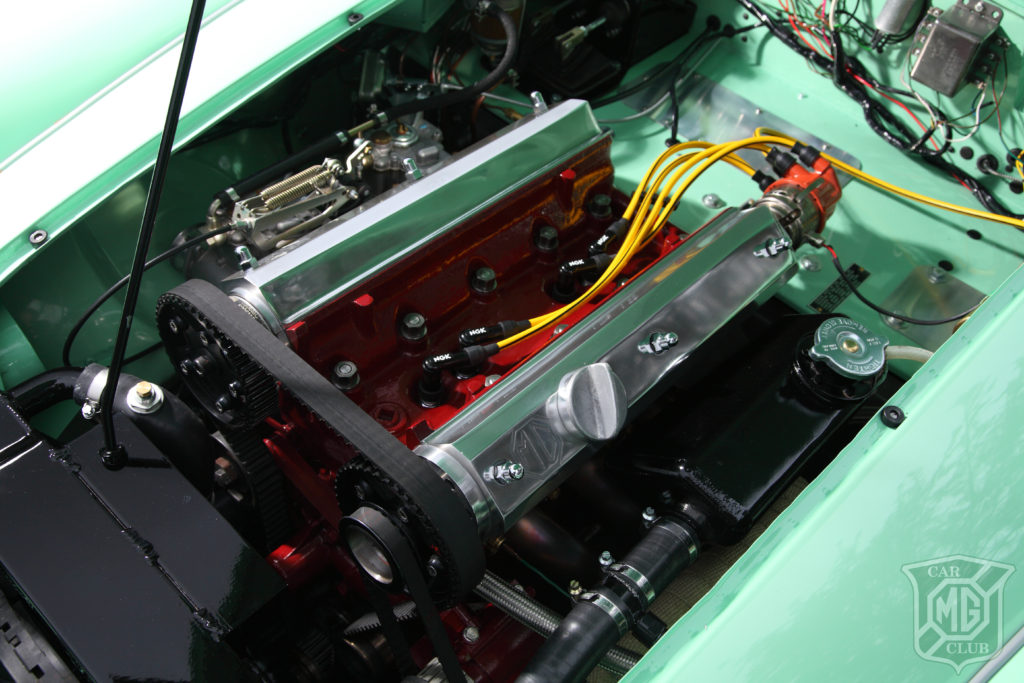

Until a year or so ago, the project had been progressing in a period-perfect fashion. Then Mark happened upon a rather interesting engine. “I had most of the parts to build a standard Twin Cam engine,” he reveals. “But, a little while back, I had the opportunity to buy a fast road/race Twin Cam. It was too good to miss. This engine, which is mated to a Ford Type 9 five-speed gearbox, is built around a modified five-bearing MGB block, bored to 1900cc, with forged pistons, rods and crank and a Zero Exhausts stainless steel manifold and system. It’s also been converted to belt drive and utilises an external oil pump, camshaft-driven distributor and electric water pump. The timing cover is laser cut. Power is 180bhp. I’ve fitted the engine in such a way as not to deviate too far from the original underbonnet appearance, but give it some ‘wow’ factor.”

Thoughts

This Twin Cam, which is sublimely built, detailed and finished, certainly possesses the wow factor. Mark has unquestionably delivered on his ‘racing’ vision, and he and all who helped him deserve a collective pat on the back. I’ve driven modified Twin Cams on a test track and I’m well aware of how capable they are. Mark’s is no exception. The chassis is impeccably balanced, the brakes impressive, but it’s the engine that truly deserves the superlatives. It’s a wonderful and potent evocation of Palmer’s original design intent and so, so capable. Silky smooth, surprisingly quiet, remarkably tractable, and perfect for road, race or hillclimb/sprint use, it makes this particular Twin Cam very special indeed.

Thanks to:

Mark Tossell – 07795 670881

Bob West MGA and Twin Cam Specialists – 01977 703828 http://www.bobwestclassiccars.co.uk/

Anthony and Paul

Paul Turner

Piers Hubbard

Member’s Bio

I’ve been a member for over 27 years. My first MG was an MG Metro. This was replaced by a Midget. Next was an MGB GT, which I also used as my company car. I then bought the MGA, the one I supercharged; this was around 21 years ago. I’ve also owned an MGF Trophy, another Midget, the red MGA Coupe which I sold to fund the Twin Cam and I have another MGA in bits. It was previously stored in a loft for over 40 years! And, I’ve just sold my MG ZS company car which had done 230,000 miles.

MGCC MGA Twin Cam Group

Established in 1996, this group helps and supports owners and provides technical advice, model information, holds archive material, and has lists of the cars currently known to exist. Of the 2,111 cars produced, just over 1,000 are thought to have survived.

Tech Spec:

Chassis

Steel box section

Wheelbase: 7ft 10in

Track Front: 3ft 11.9in

Track Rear: 4ft 0.08in

Suspension

Front: independent, lowered coil springs, wishbones, lever arm dampers

Rear: live axle with semi-elliptic leaf springs, lowering blocks and lever arm dampers.

Steering

Rack & pinion

Turning circle: 32ft

Brakes

Front: 103/4 in Disc

Rear: 103/4 in Disc

Cable-operated parking brake

Wheels

Dunlop peg-drive steels.

Tyres: 185/65/15 radials

Engine

4 cylinder DOHC

Modified and converted five-bearing MGB block

Belt-driven

Twin Weber 45DCOE carburettors

123 Electronic distributor

Cubic capacity: 1900cc

Power output: Approx 180bhp @ 7000rpm

Torque: not known

Gearbox

Five speed manual, synchromesh on all forward gears

Performance

Max. Speed – 135mph (est.)

Acceleration – 0–60mph 6 secs (est.)

Overall fuel consumption – 25mpg (est.)

MG Car Club

MG Car Club