Why MG?

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

Racing has always been a part of the MG Car Club’s DNA, and the following article comes from the May 1961 edition of Safety Fast! It was written by Richard Ide, a former racing driver, and he explained at the time why he chose to race in just MGs. What’s brilliant is that many of the reasons that Richard gives are still true in today’s MG racing.

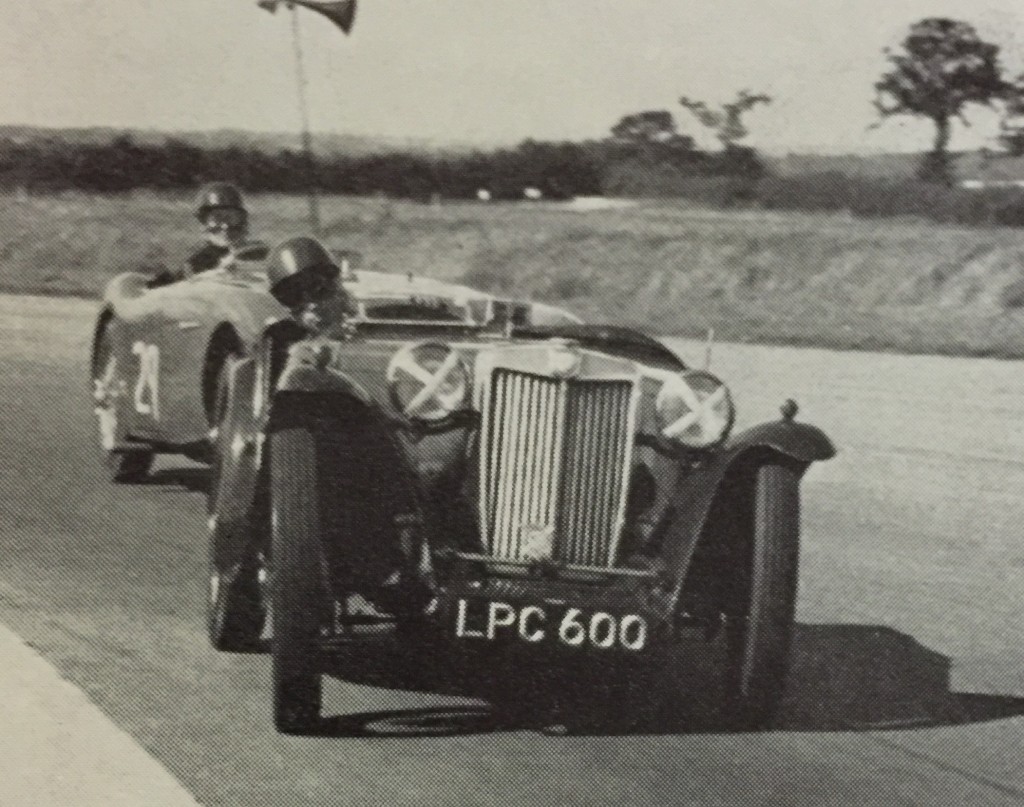

For five years Richard Ide has raced only MGs – a TC, a TD and now an MGA. In this article he gives his reasons for his choice.

Why MG?

Surely a Lola or a Formula Junior car would suit you better as a racing machine? How often have I been asked that during the last couple of years – and how often have I shrugged my shoulders and changed the subject! People race motor-cars for different reasons and with very different bank balances.

My income is such that to race at all leaves me without a penny to spend on anything else. Any car which is bought must be cheap to run, easy to prepare, fun to drive, have readily available spares, and above all, hold its market value until such time as its racing days are finished. Tall order, you may say, and you would be quite right, but after much brain-searching and advice from my father, it was decided years ago to buy an MG TC, which we felt might fit the bill as a newcomer’s racing car.

And so it was that in November 1956 I became the owner of a 1947 MG TC in quite excellent condition, and virtually standard. The previous owner had been an enthusiast of 76 years, who pride and joy the car was, and who, I felt sure, had never driven it over 45mph.

At the time I was 18 and an apprentice with one of the Big Five, and needless to say money was extremely short. In the interests of thrift and reliability, it was decided not to modify the car, but to concentrate in keeping it in one piece and to learn the elementary rules of motor racing. Although I did not aspire to become World Champion, I felt that racing had to be taken quite seriously to ensure the safe passage of my own skin, and those of other drivers.

Right from the start, the TC proved that all the faith we had in her was well founded. She proved easy to handle, relatively cheap to run and fast enough to keep hr end up in the handicap races for which she was entered. However, she had one great vice-vigorous understeer, which led to monumental consumption of front tyres. The front wheels also proved troublesome by throwing their spokes away every so often, but this was cured by fitting spokes which were belled out at the ends.

A tune-up for the TC

By the end of the 1957 season, the motor racing bug had me firmly by the pants; I considered that I had outgrown the TC and learnt all that there was to learn from it. How wrong I was. Lack of finances dictated that the car would have to run for another season, so it was decided that a little modification would not be out of place.

The engine was stripped and re-bored. The crank, rods, flywheel and clutch were balanced, and the compression ratio raised to 9.5:1. Larger inlet valves were fitted and 1 ½ in. SU carburettors substituted for the 1 ¼ in. units, with the incorporation of the TF 1500 inlet manifold. One of the cam followers had become damaged at the end of the season with subsequent damage to its sleeve, so a new one was up 0.020 in. larger than the old one, and the sleeve bored out accordingly. All the machining was carried out in the apprentice school of the firm for whom I worked, at a total cost of, I believe, 17s. 6d.

During the previous season the clutch had proved quite inadequate, so the springs were replaced by stronger ones and a racing lining fitted. The steering box was re-bushed, and 16in. rear wheels replaced the original 19in. ones. This reduced the car’s tendency to wander, by increasing the castor angle of the front wheels, and, coupled with telescopic shock absorbers, made it much more pleasant to handle. The various bits were carefully re-assembled and equally run in, so that in April, we started racing once more with a meeting at Brands Hatch.

The TC had been entered for the production sports car race, but had been transferred by the organisers into the unlimited sports car race alongside Listers, HWM’s and the like. However, despite my misgivings, the old girl managed to finish ahead of a rather uncontrolled Lister-Jaguar and enjoyed a fine dice with a Tojeiro-Climax.

Other events followed fairly quickly, and I began to realise how lightly I had scratched the surface of racing during the previous season. The TC was a most forgiving car, which could be relied on to get me out of trouble should the need arise – and it often did. In their second season, drivers often go through a stage of blatant over-confidence, and it was through such a phase that I passed (fortunately) during that second year.

I felt that I just could not go wrong and if trouble arose the TC would get me out of it, which it always did.

Low flying at Silverstone

An incident occurred at about this time which made me realise just how near the ragged edge I had got. The old lady would normally go flat out-just-through Copse Corner at Silverstone, and one day I arrived to find that she would not. There could have been many reasons for this, but it is one of the things that quite often happens to a racing track.

Now, my lap times were suffering through this and I got a bit annoyed, so during the first race I crossed my fingers and banged it in ‘flat’ as usual. The front end went about halfway through the bend, which was normal, but this time it would not come back, so I had to take to the grass. By this time I knew most of the grass at Silverstone quite intimately, but I could not have used this particular piece before because I hit a cross-gulley, which projected me skywards at some speed.

My sole contact with the car was through the steering wheel, and I felt a certain sympathy for National Hunt jockeys. I was quite certain that she was going over, but once more the MG came to my rescue and made a perfect four-point landing to re-join the track in the vicinity of Maggots. I lifted off next time round….

During the season, my father and I had decided that, if the TC was stripped of all unnecessary weight and fitted with a 1 ½-litre engine, there would be little from Abingdon to beat it; as it was we got a bit upset when any but the best MGA drivers finished ahead of us. Even today, I believe had we done this it would still be very hard to beat, but my good friend Peter Tomei stepped in before we started work.

For the past two seasons, Peter had raced, most successfully, that crème de la crème of T-types, the Bill Constable TD 1500, and it was at a most attractive price that he now offered me this car. By collecting a few 21st Birthday presents in advance, and other obscure means, sufficient money was acquired and Peter parted with the TD. Meanwhile the TC was sold – after two seasons racing – for £70 more than was originally paid for it.

That must prove something or other.

A really fast TD

Although the Constable TD was quite a well-known car, few people were allowed to know why it went so fast. For a start, the handling was far superior to that of any other TD I have come across. The front springs were shorter, and the rear flat, which lowered the car, and there was a roll-stabiliser fitted at the front.

In addition to the standard dampers, adjustable racing Houdaille units were fitted. The rear axle and gearbox were standard, but the clutch was much stronger, incorporating Bristol springs. The bottom end was balanced and stronger rods used. The real performance came from the cylinder head, which was much modified, in conjunction with the use of a full racing camshaft. Quite a few people had a go at this head, which was machined to give a compression ratio of 10:1.

The last firm to breathe on it was Barwell Motors, but I believe Bill Constable himself did most of the chopping about. The division of the inlet ports through which the head stud projects was completely removed, the head being secured at these points by Allen screws.

The valves were much larger than standard and were replaced quite regularly (a practice I would strongly recommend to anyone who wishes to race one of these units regularly; the head have a nasty habit of dropping off after a while). The exhaust manifold was of the type described in the MG Tuning Manual, and no great attention was paid to silencing.

An oil cooler made out of an old refrigerator unit was used, and the oil pick-up was through a tubular strainer which ran the length of the sump and emerged at the front. Many other small mods were incorporated in this engine and the final output was reputed to be 98bhp, though I cannot vouch for this.

There had been very little lightening carried out, save for the use of an aluminium bonnet and small bucket seats. This interesting combination covered the Gosport standing ¼ mile in 17 seconds in the hands of Peter Tomei.

Cornering Technique

The TD was a very easy car to drive, but required a different technique altogether from the TC. This ‘TC technique’, if it can be called such, consisted of hammering into the bend at a seemingly impossible speed and banging the wheel over. At this point the car would quiver all over and slide about, so that by the time the apex had been reached enough speed had been lost to allow the car to get round the rest of the corner.

If I leant out far enough, I could see the leading edge of an exceedingly wobbling front wheel poking out past the side of the mudguard. After a while I didn’t lean out any more, which completely restored my confidence in the car.

The TD was equipped with racing tyres at the front and Michelin X at the back, and at each meeting knowledgeable bar-proppers would gravely warn me of the folly of this. The result of the odd tyre combination was to make the car gently understeer until a point was reached, when the tail would suddenly flick out, but somehow it gave sufficient warning and the driver was always ready for it.

Obviously the TD could not be thrown into corners as the TC could, but the overall effect was better as the TD would leave the bends at a much higher speed; whereas the TC felt much faster, against the clock the TD was better. The TC was far better in a slow corner, where a delightful power-sliding technique could be employed, and to have a car over on opposite lock with the taps right open is one of the finest thrills that life has to offer.

Incidentally, it is interesting that those tyres still had plenty of tread on when I sold the car, and they had done some two-and-a-half-years’ hard racing.

My season with the TD was fairly trouble-free except that I used to burn out the brakes regularly, but that was my fault. It was a delightful machine to own and a most docile road car, although it was never used as such. By the end of the season, I was hankering after a better class of racing and this the TD could not provide, so reluctantly it had to go.

It was sold for a loss of only £10, so that I was £60 in pocket out of the two cars, if you follow that reasoning. At about this time my apprenticeship ended and I got a job with a retail firm in the Midlands; this, coupled with severe financial strain, made me decide to give racing a rest for a year.

Enter the MGA

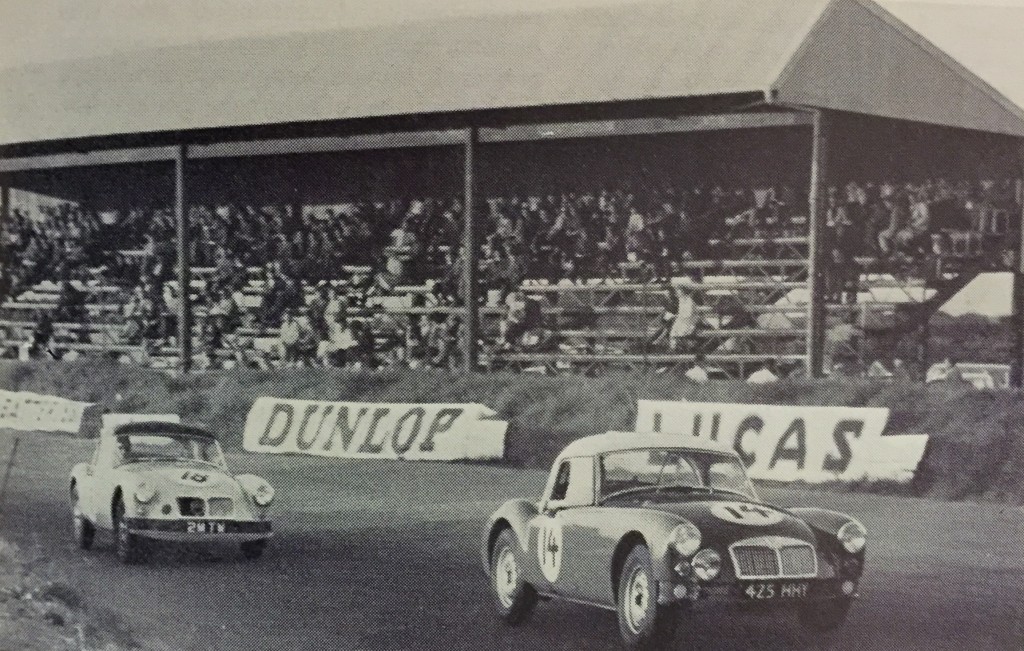

To my considerable surprise, I found this new firm tolerant towards my mad sport, and with the onset of spring and improved finances, I could stand inactivity no longer. On the Thursday before Easter a shining new red MGA 1600 stood in my garage. The idea was to run it in the Autosport Championship races, in odd club events and in Ireland.

The car was immediately dismantled – and here I made a big mistake, for the racing season had already started and the whole preparation of the car was rushed. I should have been well advised to leave it more or less standard and carry out the expensive mods at the end of the season. The 1600 is a pretty quick car as it stands and we certainly made it very little quicker, although in the road-holding department we did improve things. As things turned out, we spent half the season and our first few races playing about with it, and it never did go to my entire satisfaction.

I do not wish to dwell on the modifications which have been carried out on this car, because it will be raced for at least one more season. My big mistake was to fit a proprietary (not MG) racing camshaft, which robbed the engine of all its torque below 4200rpm and didn’t enhance the performance to any noticeable degree at the top end.

During the last race of the season, the Three Hours at Snetterton, the hardening failed on the shaft and the lobes on most of the cams wore down, leaving me with no poke at all; most disconcerting. We suspect that this shaft was never machined correctly in the first place.

Preparing for racing

The road-holding of the MGA is so impeccable that very little need be done to turn it into a delightful racing car. It is advisable to fit an anti-roll bar to the front and competition damper valves are an advantage. The 4.55:1 rear axle ratio is very useful, as are close-ratio gears for the box. Our synchromesh on top only lasts a couple of races, so we don’t bother to replace it now. When the box was stripped at the end of last season, nothing was damaged and no part needed replacement.

Bearing in mind the fact that at Dunboyne and Phoenix Park I was banging down into bottom gear each lap, this say a lot for the unit. We have fitted a special racing clutch, but this is not really necessary unless the car is raced hard and often. It is, however, advisable to hve the fly-wheel, rods and crank fully balanced, as this considerably raises the safety factor and makes the motor very smooth indeed.

An oil cooler is worth its weight in gold; we never had any bearing trouble last year with the MGA or the year before with the TD, and things got a bit ‘ot at times.

During most of last season we raced the MGA on steel cord tyres. Many bar-propping exerts condemn these tyres for racing, but they have proved first-class in every way. It is said that they break away too quickly and respond badly to correction, but by raising the pressure to 38psi front and 40psi rear, these tricks can be eliminated.

For the club man with his pocket to think of, these tyres are the answer and they last forever. We transferred to racing tyres at the end of the season. They are certainly a fair bit quicker and they allow a much wider angle of drift. This, however, is important only to the man who takes his racing pretty seriously; unfortunately, I do.

All my troubles last year were self-inflicted, and the MGA remains a truly beautiful little car to own and race. There is no car on the market selling for under £2,000 which I would rather own. I should like to race a pukka GT machine, but who wouldn’t? The MG is now ready for the battle again.

It is modified as far as the Appendix J regulations governing GT cars will allow, and, needless to say, a standard camshaft is now being used. It is a lot faster than last year, but the proof of the pudding is in the eating, and our first race could prove all our theories wrong and undo the whole winter’s work. But that’s motor racing; we shall see. R.I.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club