The life of William Morris, Lord Nuffield – Part 1

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

By Peter Cook

This year is an important one for MG enthusiasts. It is 100 years since the sale and delivery of the first Morris car on March 28, 1913 to Stewart and Arden in London.

Not only is it the centenary of the first Morris, it is also 50 years since the death of William Morris, Viscount Nuffield. Without William Morris there would not have been Morris Garages and hence no MG marque.

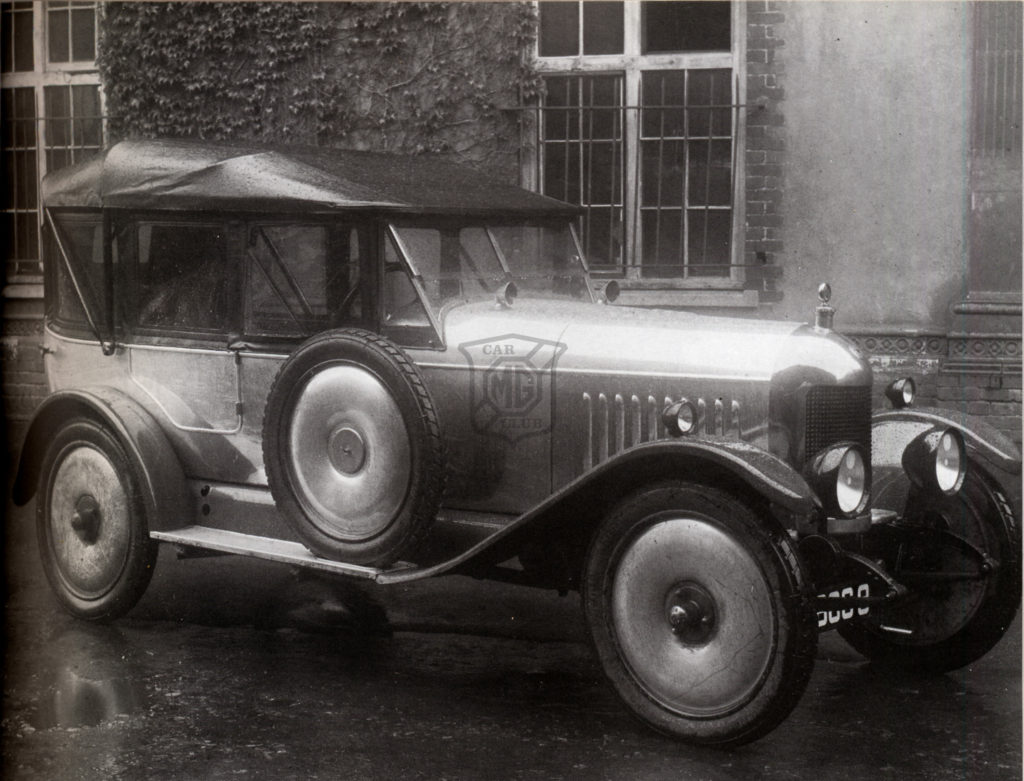

The MG historian Wilson McComb claims that 1923 saw the manufacture and sale of the first MG, in which case 2013 is the 90th anniversary of the marque. Morris Garages’ manager Cecil Kimber ordered six Morris Cowley chassis which he had fitted with sports bodies and numerous other modifications, and painted in pastel colours – quite unusual at the time.

On August 11, 1923 Oliver Arkell walked into the Morris showroom in Queen Street, Oxford (three years earlier a 14 year-old Sydney Enever had joined the garage as a messenger boy). Mr Arkell liked the yellow-painted sports car which Cecil Kimber said was available for £300 – not much more than the Morris he had been intending to buy. Mr Arkell paid a deposit and the deal was done. He was a lucky man, for an error had been made and the correct price should have been £350! Even so, it took about a year for all six models to sell.

In what follows and as far as possible, the locations and current identities of the different places around Oxford where there was a Morris presence are given. Be aware though, that the only way to visit these locations is by ‘park and ride’ – Oxford is impossible to drive around today, due in part to the success of people like William Morris.

Martin Adeney observed in his biography of William Morris that beyond the world of classic and vintage car enthusiasts Nuffield, like Rockefeller, is remembered more for what he did with his money than for how he made it. It has been estimated that at today’s values Nuffield gave away about £800 million to various good causes.

These include the Nuffield Foundation, Nuffield Theatres, Nuffield Hospitals, Nuffield professorships, BUPA, the Oxford University Medical School, and Nuffield College. While cars bearing his name have long since gone (apart from MG), the Nuffield name lives on – although there must be many who are unaware of the origins of the benefactions.

William Richard Morris was born in Worcester on October 10, 1877. Morris’s father Frederick was, by Morris’s account published in Autocar in 1928, ‘a rolling stone’. Frederick emigrated to Canada at 17 where he worked as a stagecoach driver, and lived with a native Indian tribe before returning to England where he had various jobs around the Midlands, but also disappeared with no explanation for weeks on end. Finally, the family moved back to Oxford where Frederick was employed as a bailiff on his increasingly blind father-in-law’s farm.

Morris left school at 15 and signed on to an apprenticeship with a local cycle maker in 1893, but poor training and low pay led him to ask for a pay rise after nine months. He was refused and promptly resigned to start up his own cycle repair and assembly business from his parents’ house in James St., Oxford.

Most cycle assemblers bought in components from companies like BSA and brazed their own frames from standard tubing. Morris’s cycles soon became known locally and he was soon receiving orders for bespoke cycles Morris raced his own cycles and won about 100 championships over distances of one to 50 miles, and at one point was county champion simultaneously in three counties.

It was at a cycling event that he met his future wife, Lilian Anstey, whom he was to marry in 1904. They had much in common, apart from the cycling, which was to have significant later effects: both had had to support their families when in their teens, Morris from the age of 15 because of his father’s illness, Lilian because her father had abandoned his family when she was 16.

With his business doing so well, Morris rented a shop in 1896 at 48 High Street (now Fitrite Shoe Shop) and a workshop around the corner in Queen’s Lane (now Queen’s Lane Coffee House). In 1903 he was approached by another local businessman and a Christchurch undergraduate with a view to establishing a car dealership. Morris contributed much of his capital but within a year the business was bankrupt, in the main because the undergraduate squandered the funds on ‘salesmanship’ among his undergraduate friends.

This was probably the worst time of Morris’s life. Recently married, his business was in ruins. Mrs Morris sold her jewellery, which enabled Morris to buy back his own tools at the bankruptcy sale. The experience had an indelible effect upon both of them, encouraging a lifelong sense of insecurity, frugality (sometimes edging into meanness), cost consciousness, and a distrust of outsiders.

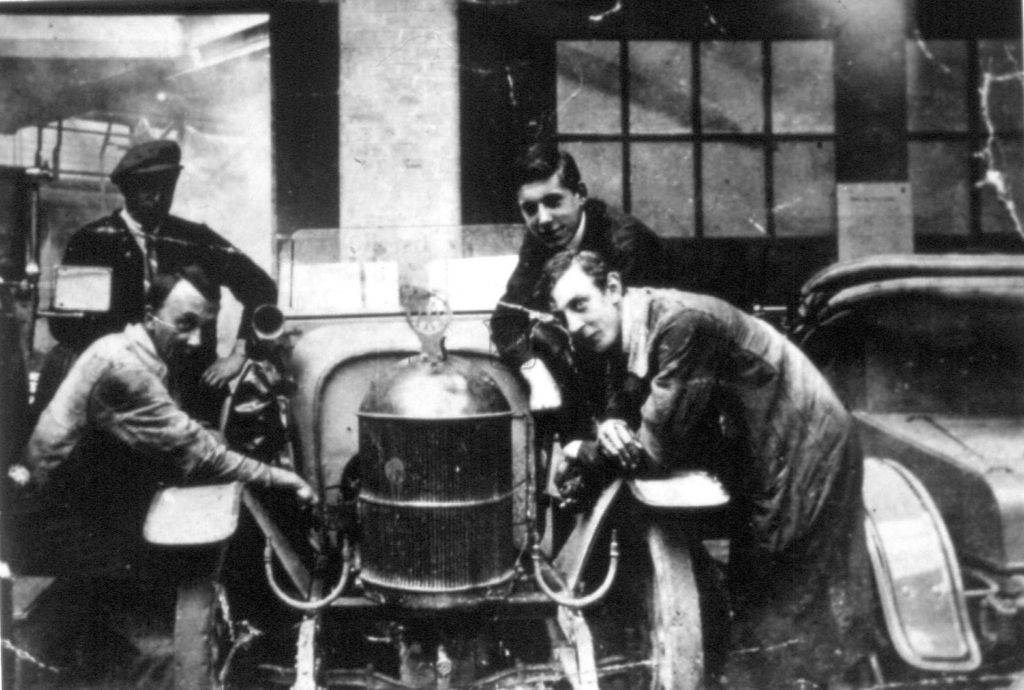

Despite the bankruptcy, Morris’s business reputation enabled him to obtain a small loan which was enough to re-establish his showroom in the High Street and the workshop in Longwall Street. He sold the cycle business in 1908 and became a car hirer, repairer and motor agent for makes including Singer, Arrol-Johnston, Hupmobile, Standard, Wolseley and Singer. Morris said that he was always looking out for the ‘demerits’ of cars, the challenge being to design a car which would “overcome others’ recurring troubles”. In 1910 he decided to build his own car from components, to be ready for the 1912 Motor Show. It was to be an affordable, reliable, light car with a powerful engine.

Meanwhile, the Longwall Street premises were rebuilt and were impressive enough for the local newspaper to call it ‘The Oxford Motor Palace’. The frontage still exists and was given Grade II listed status at the end of 2012. Morris needed more showroom space and so opened The Morris Garages showroom at 36 and 37 Queen Street, Oxford where Cecil Kimber would be appointed general manager in 1922 (now Paperchase cards and stationery, and Maxwell’s Diner).

Morris prepared his ground meticulously by visiting the 1910 and 1911 motor shows in order to have discussions with suppliers. In the event the first Morris car was not ready for the 1912 show because engine-maker White & Poppe had difficulty in obtaining castings of sufficient quality, so Morris attended with only drawings. Despite this he persuaded London dealer Gordon Stewart to place an order for 400 cars, and, crucially, Stewart paid a deposit.

Stewart and Arden advertised the Morris Oxford in Autocar on February 5 1913 and stated that: ‘The Morris is the only Light Car which embodies the joint productions of greatest British experts’, by which was meant that it was assembled from bought-in components. This was double-edged, for although many manufacturers disguised the fact that they used proprietary parts, Morris made it a virtue. Buyers knew they would not have to wait for a couple of years’ sales before the faults were eliminated.

To produce the car Morris rented the old Military Training College in Cowley which had been empty for 10 years. Gordon Stewart travelled to Cowley to collect the first Oxford – but it halted after a few yards with a broken universal joint. After repair the car managed to get to High Wycombe before breaking down again with the same fault. It was an inauspicious start for the car’s builder, but Morris made sure the fault was not repeated for the rest of the order.

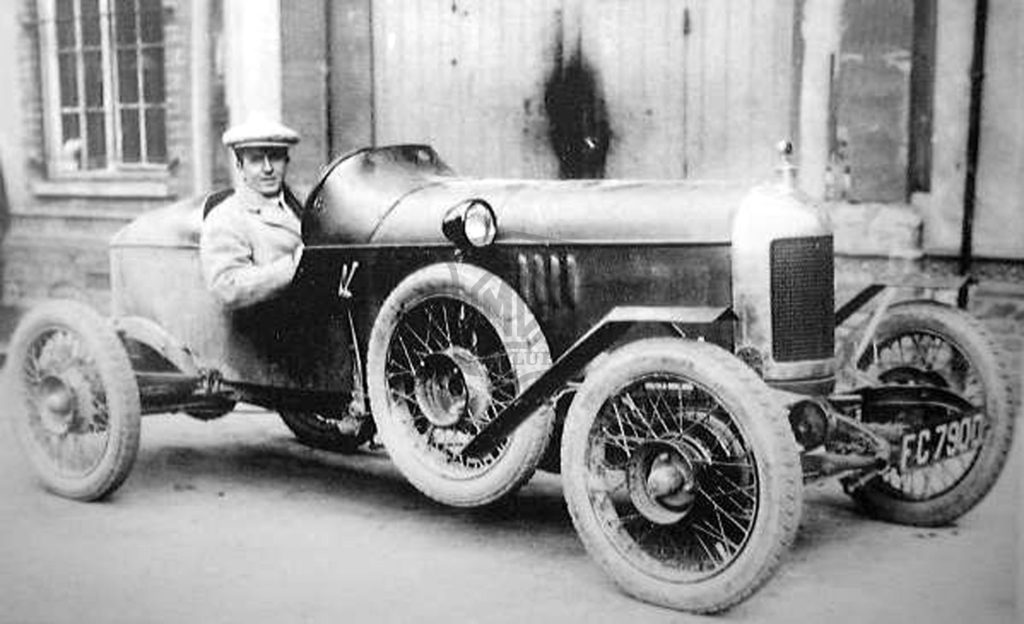

The Morris Oxford was soon established, with Autocar in 1919 reporting that ‘ …the performance and quality of the vehicle were more than up to expectations’. The two-seater Oxford sold for £180, while the four-seater Model T assembled at Trafford Park sold for £135. Morris was not aiming for the very bottom of the market, for he was aware that car ownership was extending from the very wealthy down into the professional classes. Aware of the two-seater’s limitations, Morris planned a four-seater – the Cowley.

The significantly higher body cost meant a trip to Detroit to see whether major components could be obtained more cheaply. Morris discovered that he could get an arguably better engine for £18 in Detroit rather than the £50 White & Poppe wanted. He therefore placed orders for 3,000 engines, gearboxes, axles and steering gear with various Detroit manufacturers. Consequently the Cowley, announced in April 1915, was put on the market for £162. Hardly believable today, but a noted innovation on the Cowley was a dipstick! The radiator shells were of a solid nickel alloy, allowing Morris to state, “You can go on polishing until you get right through to the water.”

Meantime, the war had started in August 1914 and Morris was soon involved in the production of shell cases, grenades, and, more significantly, the assembly of mine sinkers. These were complex, precision-made items which required careful assembly and a tight control of suppliers’ costs and quality. Before Morris got the contract skilled workers with entrenched methods at Portsmouth dockyard were producing forty a week; by the end of the war Cowley was delivering 1,200 a week.

Some cars were made, but most of his parts had to be stored. Morris did not do well financially out of war production as the Ministry took over the factory and paid him a salary. Even worse, half the engines ordered went to the bottom of the Atlantic and in September 1915 Chancellor McKenna’s War Budget imposed a 33⅓% tariff on all imported cars and components. By the end of the war Morris’s factory machinery was worn out, he had enough parts to produce some Cowleys but the market was uncertain, his capital was diminished, many of his original labour force gone, his father had died, one of his sisters had been widowed, and he was exhausted and on the point of a breakdown. Under doctor’s orders Morris spent six weeks at a German spa in 1919 and came back with restored health.

While car production got underway quickly using the stored parts, the McKenna duties meant that American suppliers had to be dropped. Morris held the manufacturing rights to the Continental engine and found a manufacturer in Hotchkiss, the machine gun maker which had relocated to Coventry in case the Kaiser’s army overran France. Although there was pent-up demand post-Armistice, by early 1921 this had collapsed.

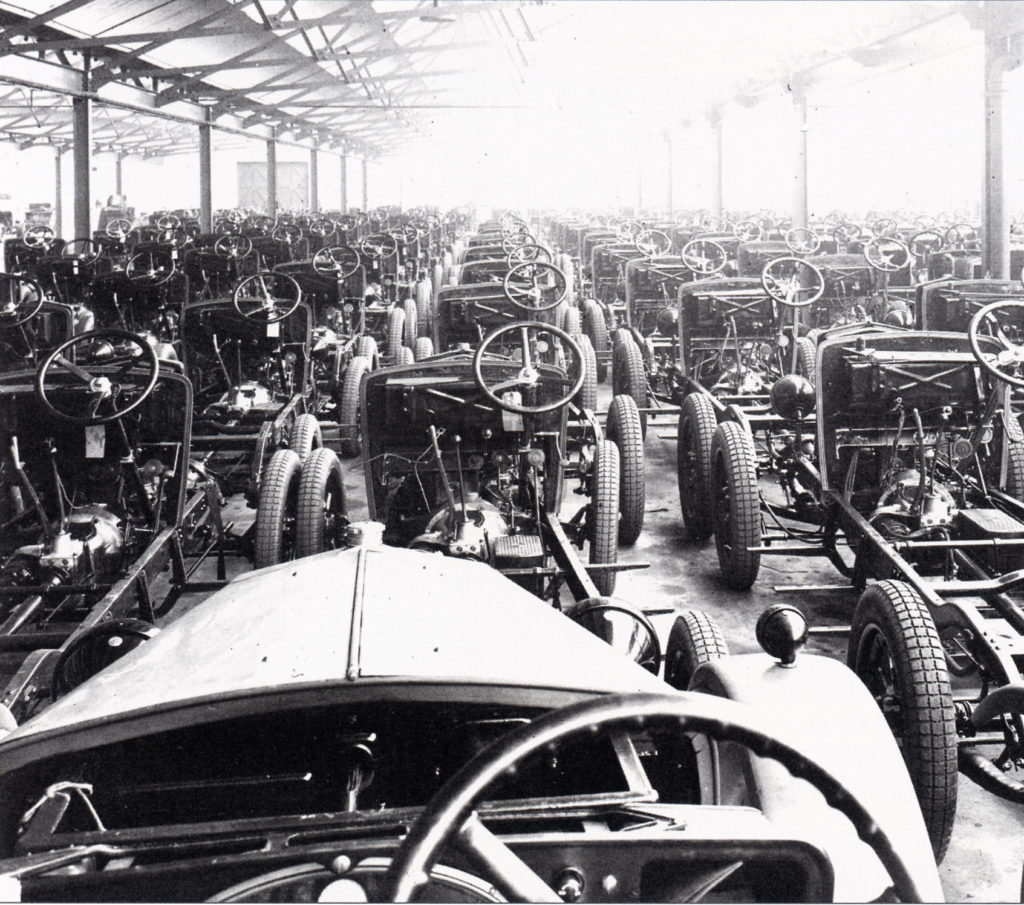

Morris’s response was to drastically cut prices every year until 1926 when the Cowley, which had cost £465 in 1920 now retailed for just £170. While the price reductions hit unit profit, leaning on suppliers and economies of scale more than compensated. Profits and sales improved considerably, so that by 1925 Morris had 41% of the UK market and had pushed Ford into third place behind Austin. In 1926 Edsel Ford visited Britain on behalf of his father and reported back: “We have been defeated and licked in Britain”. Edsel’s stubborn father eventually agreed to build the Dagenham plant which started operations in 1931.

The previous year Alfred Sloan of General Motors visited Morris in his cramped and shabby office at Cowley. Sloan held out a cheque to buy the Morris business for £11 million, Morris refused, even though the business was then valued at about £5 million. As Morris is reported to have said: “I should have been selling my country to another country, and that I refuse to do. I should have felt a traitor.” Sloan bought Vauxhall instead. In 1929 Morris received a knighthood for services to industry.

Morris’s success continued throughout the inter-war decades, but in retrospect some of the success may be viewed as storing up problems which would become especially apparent in the BMC and British Leyland years. Some suppliers failed, others were unable to keep pace with Morris’s demand, so he bought them up and reorganised them. Morris sometimes placed former supplier directors – some of whom had failed – onto his main board. On the other hand, by buying up his suppliers he also took on some very capable engineers and production managers: Hans Landstad, Frank Woolard, Miles Thomas, and Leonard Lord among others, and in addition to those who joined the Morris empire more directly – notably Cecil Kimber and Alec Issigonis.

Morris was good at spotting such talent and placing it in situations where it was most effective, but he did not like to be overshadowed by others’ success, so, invariably, there would be a disagreement and they would often take their talent elsewhere. Component factories tended to be left alone, and remain as fiefdoms for their directors and managers. Product strategy was negligible. Rather than design vehicles to fulfil a particular market need, Morris relied upon intuition. This sometimes worked well, but sometimes did not – a prime example being the disastrous Empire car of 1927.

Morris was both a heavy smoker and a lifelong hypochondriac – in retrospect, an unfortunate combination. Lilian Morris was a very shy woman, was never interviewed, and was fiercely protective of her husband’s reputation. Morris too was increasingly sensitive about his reputation. He threatened to go to law, expensively, if anyone was to publish a biography without his permission. There was one biography in his lifetime, the official one authored by two Nuffield College academics. As a young man he had been a heckler at political meetings, a pub singer, and challenged and usually beat others in his ability to drink.

None of this was allowed to get in print until after his death. Sensitive regarding his status, he allegedly bought Huntercombe Golf Club when the committee questioned his suitability for membership. Huntercombe was his only real extravagance; he boasted that his suits were inexpensive, and for his personal use he always drove a Morris or a Wolseley. The small, scruffy office at Cowley was the same when he last used it in the mid-50s as it was when he moved into it in 1913.

The Morrises never had children because, it was claimed, ‘Lilian had a horror and fear of childbirth’. Morris himself publicly stated his regret at not having an heir and therefore someone to inherit the businesses, he described it as his ‘personal tragedy’. Comparisons have often been made between Morris and Henry Ford, given they both had phenomenal success in the same industry, but the lack of an heir, particularly a male heir, severely weakens the comparisons. Morris’s later disengagement from the business, and the giving away of funds which could have been invested in the business, may be viewed in this light.

Morris’s management style is significant too. He was a brilliant entrepreneur, but less so a manager. Essentially a shy, introverted and inarticulate man, he found meetings difficult and rarely attended. He preferred to deal directly with managers, but would sometimes set them against one another. Often described as a benevolent autocrat, he would not stand for a challenge to his authority or status, but he valued loyalty.

His factories were some of the last in the industry to unionise, in great part because of the benefits his workforce enjoyed – paid holidays, sports and social clubs, medical centres, and good pay. He wrote in 1924 (republished 1954): ‘My experience is that if you look after your men, they will look after you. A low wage is the most expensive way of producing.’

MG Car Club

MG Car Club