Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

By W. Boddy

Following our articles on the successful Utah record attempt in 1959 by a combined BMC team of Austin Healey and MG, we’re reprinting an article from Safety Fast! that looks back to the time when Austin and MG were deadly rivals in the record field.

Today the majority of cars will attain the ‘magic century’ as a matter of course, although this is still a remarkable speed for a 750cc car. In 1930 it was that much more remarkable.

Now by that time the MG was firmly established, not only as a highly successful sports car but as a useful competition car with many important successes to its credit. So, naturally, the thought came to the Top Brass at Abingdon that it would be very nice if their make of car could be the first Class H (750cc) machine officially to reach a speed of 100mph.

In 1930 the fastest Class H record, the flying five miles, stood to the credit of Venatier with an obscure car called a Grazide. At the Montlhéry track near Paris it had averaged 96.57mph for this distance as early as 1927. However, what was perhaps of more concern to MG was an onslaught at Brooklands made by Austin after they had won the 1930 B.R.D.C. 500 Miles Race. Driving a normal-looking supercharged Ulster Austin two-seater with which he had shared victory in that gruelling race with the Earl of March (now the Duke of Richmond and Gordon, owner of the Goodwood circuit) S.C.H. Davis came out on two occasions at Brooklands and wiped up every record in the class, with the exception of four held by the fabulous Grazide. This included records formerly held by other Austin Sevens and a Rovin J.A.P. With a special four-speed single-seater Austin, Davis also attacked short- distance records and left the fastest speed (fs) kilometre at 89.08mph. It was this record that Cecil Kimber, head of the MG Car Company, backed by Nuffield, sought to break.

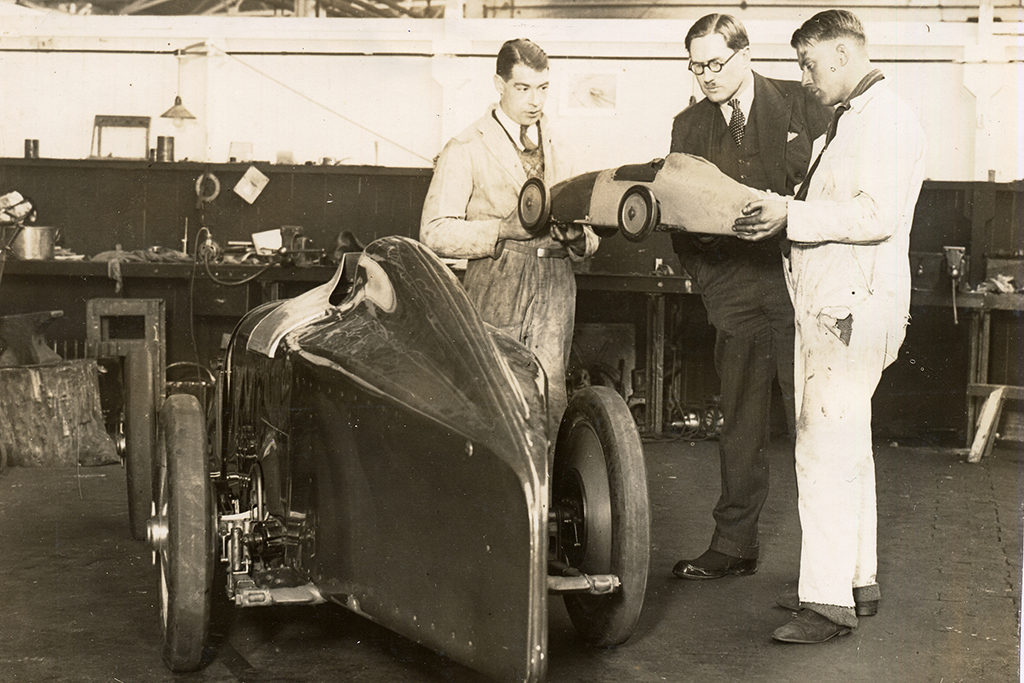

For the purpose, an MG known as EX120 was prepared. This started life as the prototype of the 1931 racing MG Midgets and was a very considerable advance on the current ‘M’ type Midget – perhaps John Thornley will say this is an understatement!

Into this new chassis an engine was installed which had been evolved by J. Palmes in the rooms he shared at Cambridge with George Eyston. Palmes had reduced the size of the MG Midget engine from 847 to 743cc by linering down the block by 3mm and reducing the stroke by 2mm, with a new crankshaft. The idea had been to use this engine to attack the long-distance Austin records, running it unblown. But Sir Malcolm Campbell had left for Daytona on one of his periodic onslaughts on the Land Speed Record and had taken with him the four-speed single-seater Austin to see whether it would go faster on the sand than it had done for Davis at Brooklands.

So, it was decided to supercharge EX120, a perfectly logical development in view of the fact that Eyston was to drive the MG and that he was at the time closely associated with the Powerplus vane-type compressor.

One of these superchargers was fitted to the new Class H engine, driven by chain and sprockets from the front of the crankshaft, enabling the ratio of the drive to be altered easily if required.

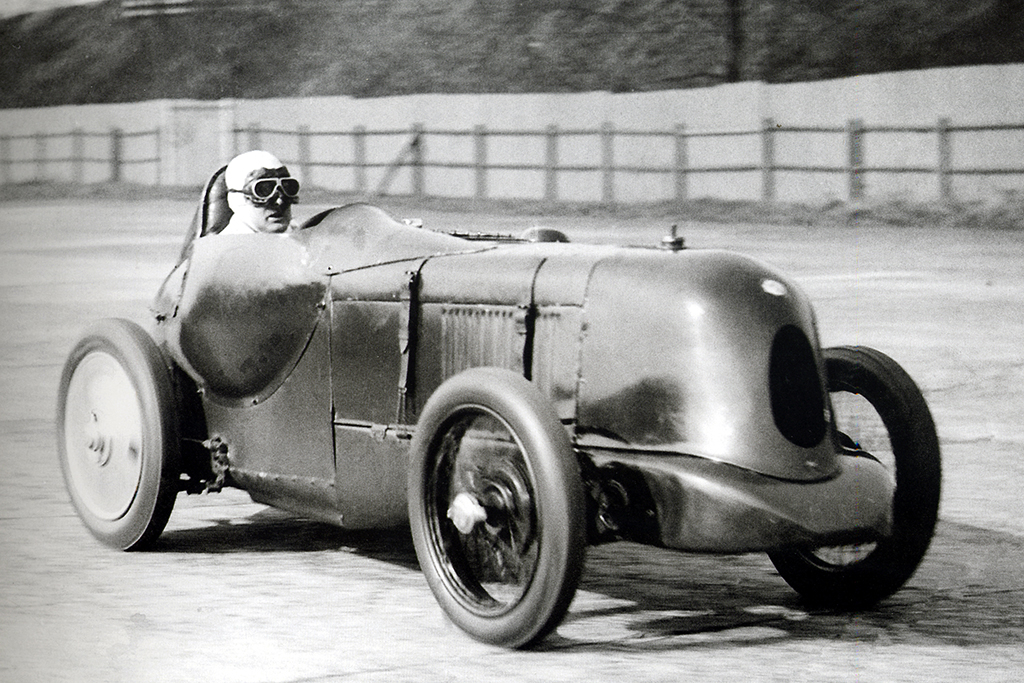

The year 1930 was nearly over by the time the car was in one piece, and Brooklands was closed for repairs to its battle- and weather-scarred surface. However, resource is one of the by-products of Abingdon, so EX120 had its first taste of high speed on a public road. Ernest Eldridge, acting as engineering consultant, insisted that the compression ratio be raised, and then the little MG was shipped across the Channel and driven to Montlhéry in a lorry, accompanied by Reg Jackson. On December 30 Eyston made his record bid, the car running in unsupercharged form. He took three records from the Austin, covering 100 kilometres at 87.3mph, before a valve broke. The margin of speed was not impressive, and without more ado the MG was brought back to England for a blower to be installed.

Two different-size Powerplus blowers had been painstakingly tested at the factory and thus it was possible to return to Montlhéry for tests of the car in supercharged form.

Finally, after the inevitable delays due to bad weather, the larger compressor was decided upon. While some difficult tuning on a higher-content alcohol fuel was being undertaken, news arrived that Campbell had raised the Class H fs mile record at Daytona to 94mph!

Clearly, the Austin was getting near the coveted goal of 100mph. To this Eyston responded by going out after the Grazide records, which were still the fastest 750cc figures. In this he was successful, breaking the only four records not held by Austin and another in addition, the MG’s best being the fs five kilometres at 97.07 mph. The ‘century’ was getting to look a possibility…

These very fast records were captured in February 1931. They had not been lightly attained. Indeed, ‘Jacko’ and Freddy Kindell had worked so hard – 126 hours continuously, in conditions of intense cold – that, before further work could be contemplated, Cecil Cousins and Gordon Phillips were sent to relieve them. The chief difficulty had been persuading the carburettor not to ice up on alcohol fuel, for if alcohol warms humans, it has the opposite effect on the engine, especially when the gas-works are isolated away from the cylinder block on a supercharger. Cousins boxed in the carburettor, and he, ‘Jacko’ and Kindell fashioned a rough cowl for the radiator, the dumb-irons being already faired in.

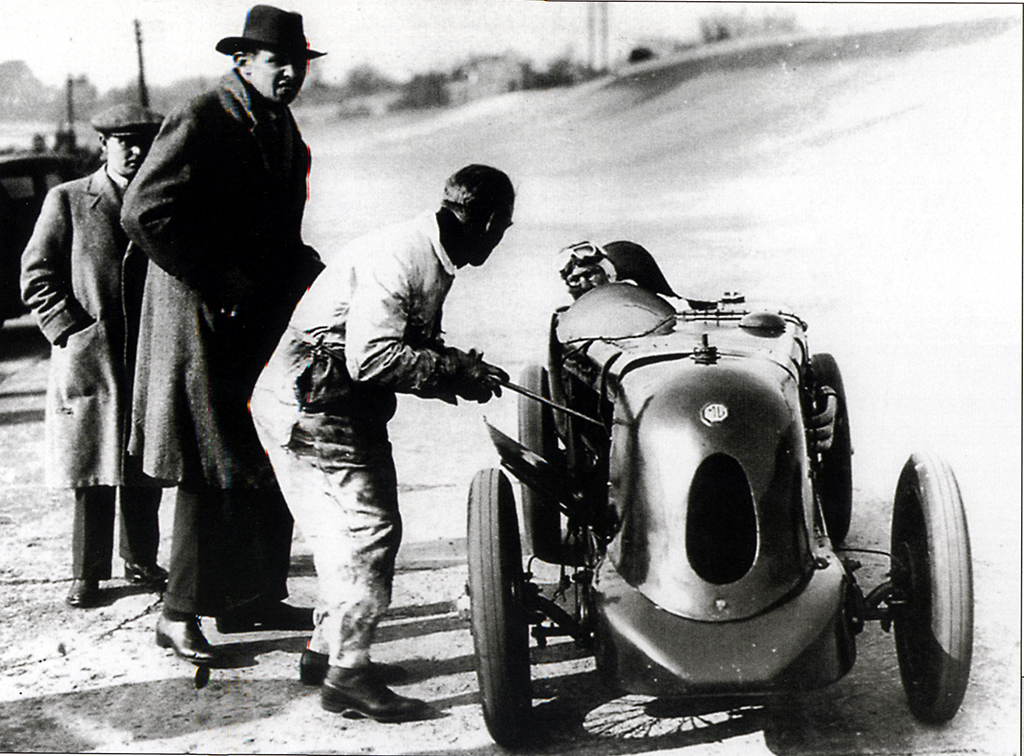

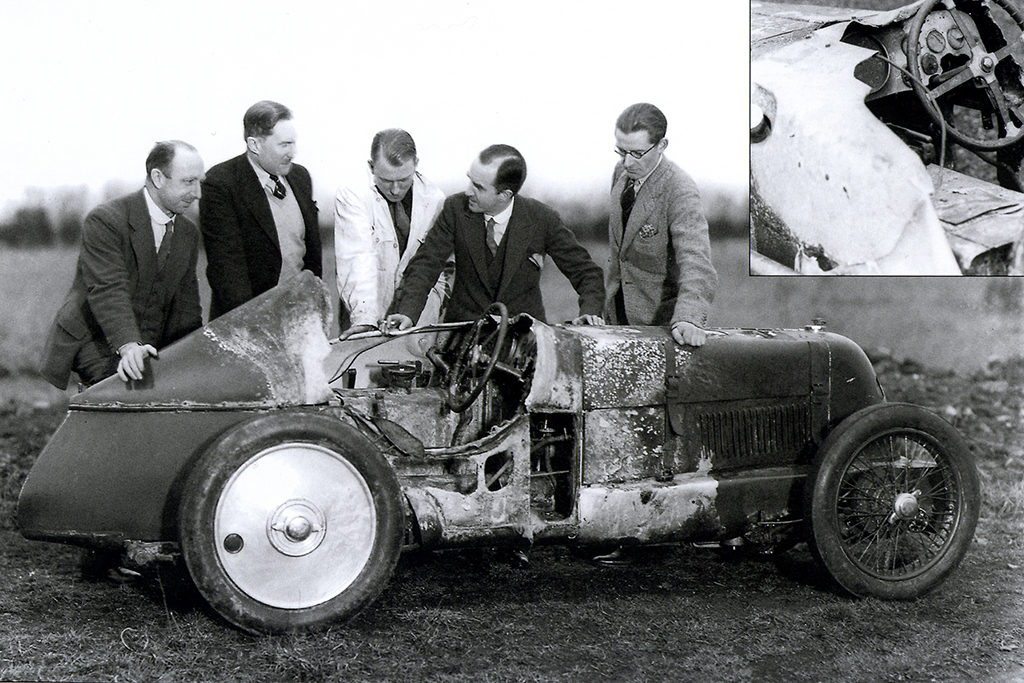

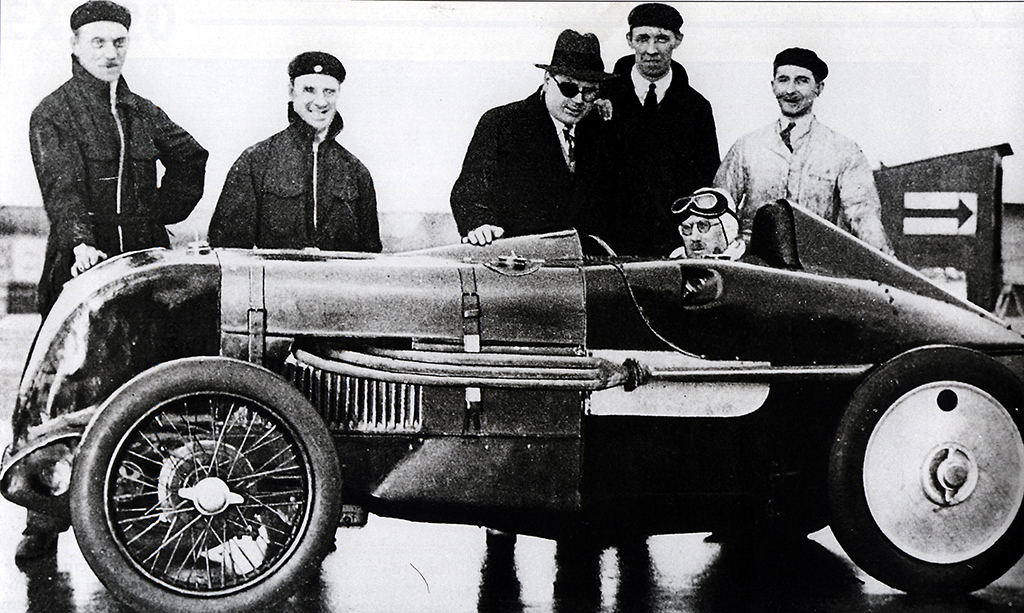

EX120 with the rough cowling made at Montlhery in 1931. Behind are ‘Jacko’, Kindell, Eldridge, Cousins and Phillips

It is amusing to look back and recall that ‘Jacko’, having no faith in French lorries, had brought the superchargers and a spare engine out from England on an MG Tigress experimental chassis from which the ‘Double Twelve’ 18/80 MG had been evolved, while the superchargers had been tested for two whole days at Abingdon, driven by an 847cc Midget engine. Time was creeping on, a way it has, with 100mph from a 750cc car seemingly in the grasp of Austin or MG. Austin had a new, properly streamlined car in hand, but MG decided to stay at Montlhéry and see what they could do with EX120, which was virtually a two-seater with high radiator and bonnet. Eyston, record-breaker extraordinary, stood by for another go.

On the appointed day the track was wet (a nasty hazard on smooth racing tyres) a stiff wind was blowing, and, to add insult to injury, the timekeepers crashed their car on the way from Paris, leaving but half an hour of daylight. But hard work had its just reward. After a sudden storm of hail had abated George Eyston set off and the little MG ran beautifully. Engine speed was up to 6,500rpm; Eyston rammed down his foot until 7,000rpm showed up and set off on his 10-mile sprint. At times the car snaked alarmingly as its driver steered with one hand and sought to maintain pressure in the fuel tank with the other, and the tense observers thought they heard misfiring just as the attempt was nearly over. But EX120, most gallant of prototypes, held together; four Class H records fell, from five kilometres to 10 miles. But what really counted was that every one of them was taken at well over 100mph, the fastest being the five kilometres. at 103.13mph. MG had beaten Austin and Grazide to the magic century!

The goal had been attained! It is pleasing to note that when this historic achievement was celebrated, the visitors’ toast was replied to by none other than Arthur Waite of the Austin Motor Company. The publicity resulting from being the maker of the first 750cc car to exceed ‘the ton’ was exceedingly important to both Austin and MG companies, for both were selling small sports cars which were based on popular baby-car designs. But, beaten, Austin showed no resentment, proving that sportsmanship is not confined to the track.

Having attained the main objective, MG decided to take the fs kilometre and mile records from Austin. This Eyston sought to do at Brooklands, but it was Friday the 13th (March 1931) and EX120 ran badly. In the end the records were broken at 97.09 and 96.93mph respectively, bettering Campbell‘s speed. Roughly a second of the times would have seen these distances, too, at 100mph, so it isn’t surprising that Eyston was dissatisfied and essayed a test-run that evening. But it was still Friday the 13th – and the engine blew up in a big way. A piston had escaped from captivity by way of the cylinder block. The starter motor resided in the sump…

This failure, attributed to weak mixture but possibly hastened by the use of the Brooklands silencer, was emphasised when Leon Cushman brought out the Austin and raised the figures to 102.28 and 100.67mph respectively.

Moreover, it wasn’t only Austin who battled with MG for Class H honours. Lord Ridley had his own ideas of what a 750cc record car should be like. He came to Brooklands with a Powerplus-blown 746cc twin-cam special and put the fs mile and kilometre records respectively to 105.42 and 104.56mph. Later he sustained a nasty crash which wrote off the Ridley Special, but not before the kilometre record had been set to 105.92mph. So there was not too much room for complacency at Abingdon, especially as in 1932 Driscoll set the Class H Brooklands lap record to 103.11mph for Austin, although Eyston was able to reply with 112.93mph for MG two months later, and, before the year was out, Ron Horton’s offset MG single-seater had lapped at 115.29mph. Here I will digress to remark that Austin scored a lead in this sphere, with the first 750cc lap at over 120mph (Dodson, in 1936, at 121.14mph) but that Brooklands honours now rest with MG for all time (Harvey Noble, in 1937, at 122.40mph). These fantastic speeds from the ¾-litre cars had the expected repercussion on racing, in which the Class H entrants were heavily handicapped.

I am writing of record-breaking, not racing, however, and MG’s next target was 100 miles in the hour. A plan of action was put into operation which consisted of building a very special new single-seater known as EX127 and revamping EX120 as a long-distance record-breaker. Hearing of this, Austin went post-haste to Montlhéry and set Mrs Gwenda Stewart the task of trying to do 100 in the hour before MG could take this honour for posterity. This attempt failed, so Gwenda was put on to trying to raise Ridley’s speed over short distances, and in this she was successful, lifting the five-kilometre record to 109mph.

The Austin then went out for its third hour attempt, but it suffered from transmission failure and was returned to England. To this Eyston responded by setting EX120 to try for the hour record. He held the engine at over 6,800rpm for lap after lap of the French track, pumping up pressure in the tank as required, and without fireworks another historic landmark fell to MG – Eyston had covered 101.1 miles in the hour. Alas, the fireworks were to follow, for on an extra lap the car caught fire.

Somehow George struggled clear of the cockpit, which was so cramped that he had only with difficulty got into the car, and he jumped off before the flames took hold and gutted the body of the MG. He was badly burned, however, and it was some time before he was able to drive again.

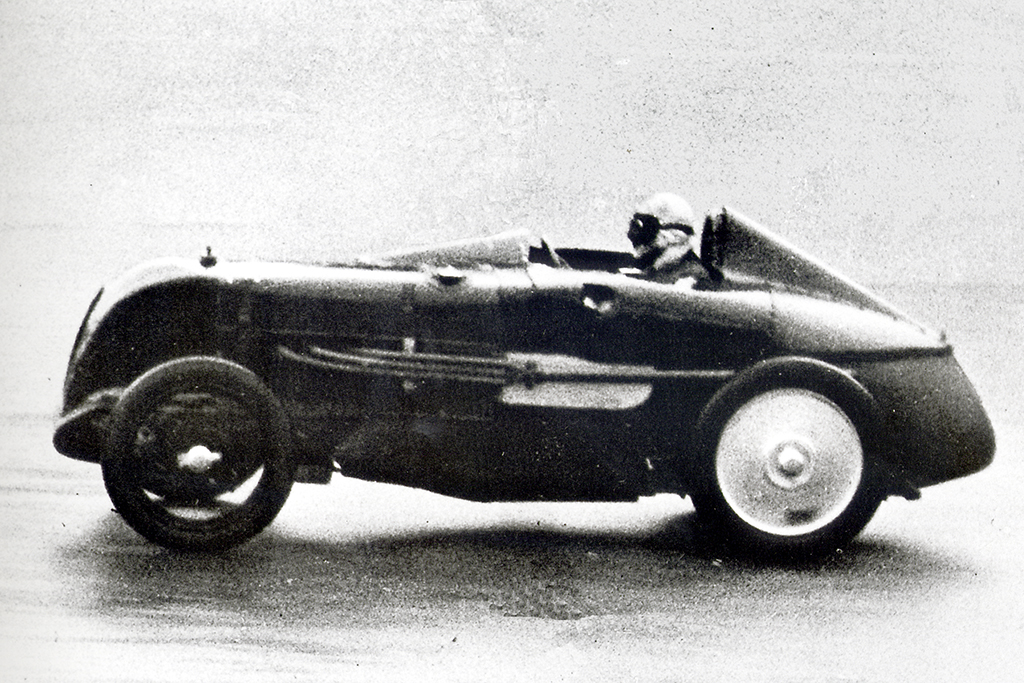

With Eyston in hospital (but the one-hour record on the books at over 100mph) diminutive Albert Denly began to test EX127, for Cecil Kimber was thirsting for the fastest-ever 750cc record. Incidentally, the comparatively narrow margins by which the records were being broken, and EX120’s failure just after the hour was up, indicate how difficult was the science of making tiny cars exceed 100mph in those days.

EX127 was afflicted with boiling, the high-set supercharger necessitating a small radiator. An aeroplane-type surface radiator was made in Paris and substituted, and in this guise the single-seater just broke Mrs Stewart’s Austin record – but only by 1mph. Eldridge drove in place of Eyston, but his attempt was cut short when the radiator burst. There was nothing for it but to take the car back to Abingdon, fit a smaller supercharger, and thus be able to make use of the original radiator. While this was being done the 1931 season was running out. Ridley tried for the MG five-kilometre record but crashed, as recounted, and Austin virtually admitted defeat in the high-speed field by concentrating on taking six long-distance records from MG. Brooklands again closed for the winter but, undaunted, MG took EX127 to Montlhéry. Just before Christmas, Eyston took the five-kilometre record at 114.77mph. He took three more records as well, all at over 114mph, but had to swallow the bitter pill of knowing that a saving of a mere 15 seconds over 10 miles would have given him an average of 120mph. Icy conditions were against further attempts, so George had Christmas at home.

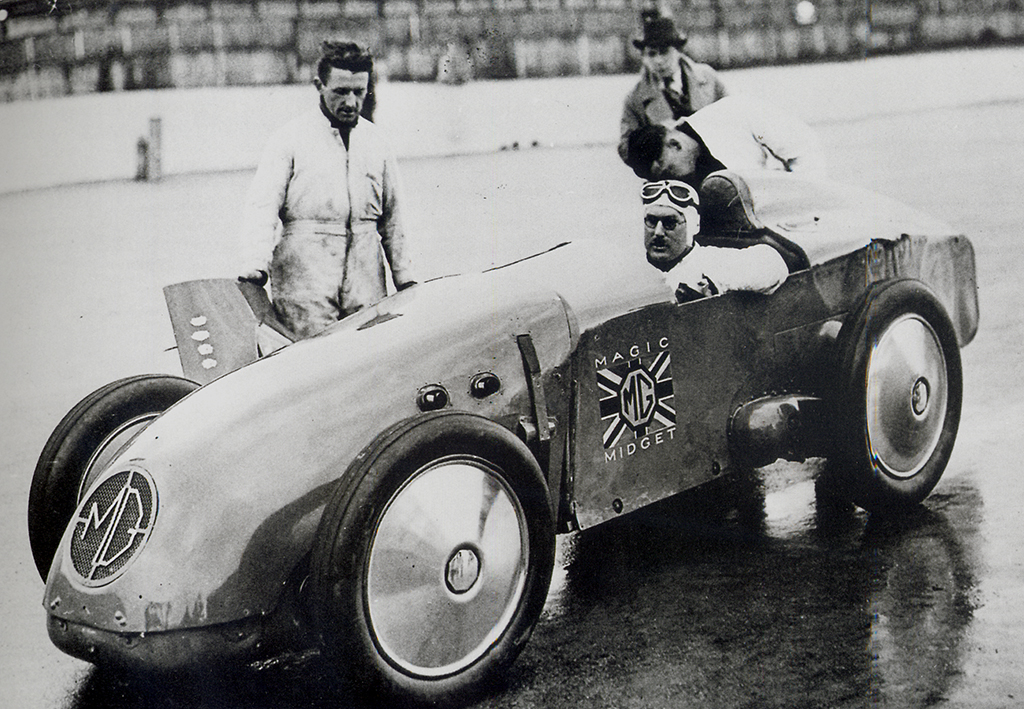

Eyston and Kimber were forced to wait patiently until the New Year. Early in 1932 the MG, now known as the ‘Magic Midget’. was taken to Pendine sands in South Wales. It suffered all the setbacks so well known to those who go for records on waterlogged sands. At last all was ready, but then the timing apparatus failed just when Eyston was thought to have done 121mph over the mile. Eventually he was able to record 118.39mph for the two-way mile, his best speed in one direction being 119.48mph – so near, yet so far from the goal.

To end the suspense, let me say right away that they got there in the end! Fitted with a closed cockpit, the ‘Magic Midget’ was taken again to Montlhéry in December 1932, after having taken, as aforesaid, the Class H Brooklands lap record from Austin at over 112mph. On this occasion Eyston planned to capture all the records in this class for MG, the standing start kilometre and mile having already been taken by Hall’s MG at Brooklands earlier that season. After innumerable delays due to bad weather, George, wearing the asbestos overalls he had insisted on after the EX120 fire (he had also tried a gas-mask, but it wasn’t necessary, the covered cockpit having been partially cut away) really got going. The Class H mile record fell at 120.56mph, the kilometre at the same speed, the five kilometre at 120.5mph. Another notable landmark had fallen to Abingdon – that of producing the first 750cc car to exceed two miles per minute.

Eyston, partnered by Denly and Tommy Wisdom, went out next in a J3 MG Midget and took all the remaining Class H records.

But it is the first 100 mph, the first 100 in the hour, and the first 120mph that are the historic landmarks of the period about which I am writing. These great achievements were the prelude to many more successful MG record bids.

But there is something especially intense about these early efforts, when rivalry was keen between Austin and MG and far less was known then than now about extracting reliable power from very small supercharged engines.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club