Tales of the unexpected – Part 2

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

Peter Browning continues his story of how he came to Abingdon to run the Austin-Healey Club and ended up as BMC Competitions Manager.

It was just before Christmas 1966 that John Thornley called me into his office, sat me down and poured the traditional glass of sherry. I knew that I had either got the sack or that something serious was in the air!

“Got a new job for you,” he said. “Stuart Turner is leaving us and you’re going to be the new Competitions Manager.” That was the only time that I had any disagreement with John Thornley. I protested that I really did not think that I could do the job but, of course, I lost the argument. Stuart and I would do the Monte Carlo Rally together and then I would be on my own.

Certainly, I felt that my qualifications for doing the job were somewhat slender. Through my timekeeping experience, Stuart had entrusted me to look after the pit organisation of the MG entries in one or two events and I had been to Sebring, Le Mans and the Targa Florio with the Team (see Part 1). Stuart, at the time, was busy winning rallies and he was probably pleased to have a keen youngster take charge of the racing side which clearly did not interest him so much.

It was, therefore, with some trepidation that I moved over the road from my Austin-Healey Club office to the hallowed Competitions Department and squeezed in alongside Stuart in his diminutive office. Preparations were in full swing for the 1967 Monte and it was an awesome experience to be thrown in at the deep end and try and catch up with the organisation of this, the most complex event of all.

I remember Stuart going through the most complicated Monte service schedule which included refuelling points and, in particular, the incredibly detailed tyre service plan. I sat there giving the impression that I understood it all on the basis that somehow later I would be able to sort it all out. Stuart gave me the master plan and asked me to take it next door and make a copy. To my horror I failed to let the copying machine warm up properly, it chewed up the original and spat out half-burnt offerings onto the floor. It took me ages to piece it together again and make head and tail of it all!

This was perhaps the hardest fought Monte of all and the one that the Team so desperately wanted to win to avenge the disqualification of the ‘winning’ Minis the previous year. Some thought that we should not have entered again after the treatment that we received the previous year but that would have seemed like surrender. I am sure that it was right to go back, win or lose, and put up the hardest fight to prove the point.

Publicity photo of the new and apprehensive Competitions Manager

Thanks to critical tyre choices in changeable conditions, the work of the ice note crews, brilliant work by the co-drivers with their pace notes, Rauno Aaltonen and Henry Liddon pulled off another Monte Mini victory. This was the sweetest revenge and the perfect leaving present for Stuart who had now provided a Monte victory for each of the Team’s top drivers.

Now I was on my own and life became a blur of late night planning and worldwide travel. First came the Swedish Rally which the Team had never finished – Rauno rolled his Mini but survived to win his class. Paddy Hopkirk finished runner-up on the Italian Flowers Rally then it was chasing Porsches on the Tulip Rally. Timo Makinen got to within 46 secs of beating them and led a 1-2 in the Touring Category while the Minis took the Team Prize. Paddy was in top form to win the Acropolis Rally and Makinen scored his annual win on his home 1000 Lakes Rally. The Alpine Rally this year was to be the fastest ever and with a hot Group Vl car Paddy beat all the fancied road racers.

Longbridge wanted us to do something with the 1800 to improve its image and Tony Fall surprised us all, winning the Danube Rally. For our 1800 rally testing programme, Longbridge sent us three standard cars for evaluation. We took them to a local farm and thrashed them round a bumpy field and it was not long before all of them had complete brake failure. We discovered that on full suspension travel the flexible front brake pipes were pulled out of their sockets. Longbridge initially blamed our ‘rock ape’ drivers but later did agree that a production modification was required.

Longbridge were chuffed with our 1800 rally results which prompted us to consider a long distance record breaking attempt with this car. We searched through the FIA record books and reckoned that the two litre records were probably up for grabs so we set off to Monza with a specially prepared car.

The old banked track at Monza was just about usable although some of the sections were very rough and the 1800 would be airborne in places. All spares and tools had to be carried on the car and the only work that could be carried out at the pits was refuelling, adding fluids and changing tyres. The back seat of the car thus carried a really heavy box of spares while an extensive tool kit was set out in pockets in the rear doors.

The car ran like clockwork, lapping at 104mph, and after a long hard week we were rewarded with a great result when we took all the records up to seven days at 92.8mph. There was however a final drama when I phoned the Press Office at Longbridge with one day to go telling them that we were all set for the record at around 98mph. They said that this was much too fast because nobody would believe that an 1800 would do 98mph let alone average that for a week – so we had to cut the speed down to a more reasonable figure!

Monza ended my first year at the helm and against all odds the works Minis had won seven rallies including victory in three great classics – the Monte, Acropolis and the Alpine. It had been a very steep learning curve for me and I have to say that I had soon become aware that being Comps Manager was a very complex and demanding job.

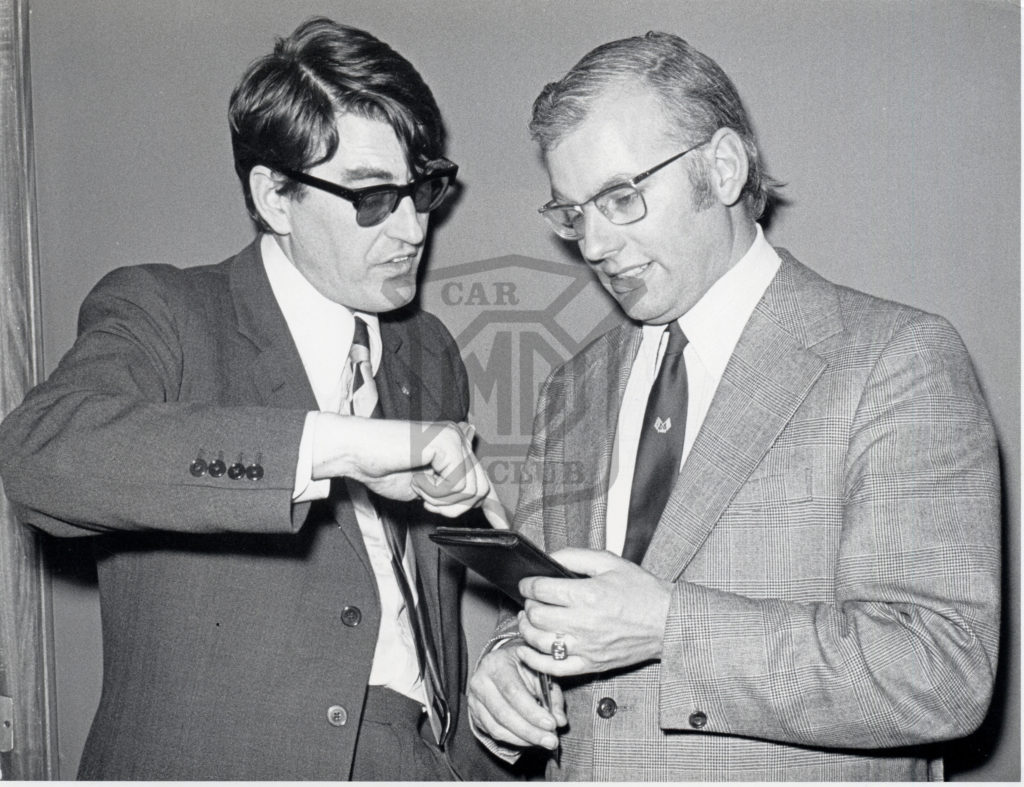

Haggling homologation details with the RAC’s Neil Eason Gibson

Firstly you had to decide which events to enter, probably most of the classic rallies, one or two events to please the wishes of particular drivers, perhaps an event which might favour a particular car and possibly events where there was special local dealer interest. Having planned the year’s programme you then had to decide which would be the most suitable cars for each event. Then you had to choose which contracted drivers to use and in some cases possibly offer support to a private owner to make up a team entry.

When the regulations for the event arrived you had to go through them with a fine toothcomb to see whether there were any unusual local tweaks – and often refer to the original text to make quite sure that the English translation was absolutely clear. With the regulations at hand this would be the time to confirm which cars to enter and in which class and category to ensure that you could achieve the best possible promotable results. The specification of the cars would be considered with possibly slight variations to the build sheet depending upon whether the rally would be run in hot or cold conditions, rough or smooth terrain.

When all these decisions had been made it was time to start booking hotels, making travel plans and bookings and possibly contacting the local dealer to see whether they could offer any help and local advice. A decision would then be made about a recce, whether you sent all the crews entered or whether the job could be done by just one crew. This would entail making a road book of the whole route and pace notes for the special stages; recce cars would have to be allocated and prepared and another schedule of travel and hotel bookings.

After the recce would come one of the most difficult but important tasks which would be to set out the service plan for the event. Using the information from the co-drivers on the recce (never ask the drivers, they seldom know where they have been!) decisions would have to be made as to how many service cars would be needed and how they should be deployed. Each service crew would have its own rally style schedule detailing accurate information on the location of service points with distances and time allowed between the points.

Throughout the planning, of course, consideration had to be given to the budget which in the early days of BMC was negotiated at the start of the year. Inevitably at the end of the year there was an awkward review meeting when the Comps Manager had to explain why he had overspent. When the team had enjoyed continued success there were seldom any problems. Under BL rule, however, things became very different, and individual budget approval had to be negotiated for each event and overspending had to be explained.

The complete event planning would take probably two months, perhaps six months for a major event like the Monte – even longer for an epic such as one of the round-the-world Marathons. I soon learnt that there was not much time for any social activities.

A Comps Manager should always try and keep an eye open for up and coming driving talent and I very soon found that there was no shortage of young drivers who felt that they only needed one chance to get behind the wheel of a works car to prove their talent. The keener ones would turn up at the works, often unannounced, and take you out to lunch to try and persuade you to give them some support. Many of them tried to prove their driving skills on the run through the country lanes to the pub!

The introduction of the BMC Bonus Scheme was the savour to this situation which paid out money to those who gained success (at home and overseas) in specified events. The response to the many private owners’ phone calls was to say, “You go out and prove your potential in your own car and at your own level and if you are successful you will be financially rewarded.” At the end of the season a review of the Bonus Scheme payments gave a very clear picture of who were really the up and coming hopefuls. And I did not have to experience the drive to and from the pub!

Checking tyre wear with a Dunlop technician on the 84 Hour Marathon

By the time I took over from Stuart we were really expected to win every rally we entered and I have to say that I found this a bit spooky not to mention putting a certain amount of pressure in my direction. I was soon involved in the regular pre-event advertising planning meetings which were to determine the format of the success advertising after the event. Manufacturers did a lot more success advertising in those days than they do today and the advertising budgets were considerable.

For major events full page advertisements would be booked in most of the national papers and the motoring magazines and often support advertising would be done by our trade supporters such as Castrol and Dunlop. At these meetings we would forecast possible results in terms of outright wins, category and class wins, team awards etc. Copy would be written there and then covering all results permutations so that when I phoned to give the final results the advertising boys could mix and match the copy to suit. Nobody seemed to consider at the time that we might come home without winning anything!

From my first trip with the Team I could see why the mechanics had a reputation for being the best in the business. However it was significant that few of them came into the Department with any specialised knowledge or experience in the preparation of competition cars. The majority started as tea boys or apprentices who at first were allowed to clean the cars, change the wheels and tyres, perhaps later strip an old recce car that was to be written off, then slowly learn the art of car preparation by working alongside senior mechanics who themselves had climbed the same ladder of experience. This is in total contrast to the works rally teams of today where personnel are drafted in with specialist experience in chassis work, suspension set-ups, engines or transmissions and the level of individual high-technological qualifications is amazing.

The procedure for building the cars at Abingdon was also totally different from today as each mechanic was personally responsible for the complete preparation of his car from a bare body shell upwards. The mechanics assembled suspensions, hand-built the complete engines, transmissions, body modifications, interior trim work, running-in the car and fine tuning it – everything with the exception of the electrics which were done by a resident Lucas specialist. Whenever possible the mechanic that built the car also went out servicing on the event so that he could also look after ‘his’ car. All of the cars were built up according to a carefully detailed build sheet and with the exception of one or two very minor points, and personal driver preferences, all of the cars on an event would therefore be almost identical.

The Team unquestionably benefited from operating within a self-contained factory that was very much pro-competitions and whose staff were always able and willing to supply ancillary services when needed. The heads of many departments were old timers with memories of MG’s former racing and record-breaking activities and they did not need much persuasion to help out with requests for help and advice if needed.

The detailed planning of our Monte organisation was without question an enormous challenge and quite the most difficult event that we tackled. If you think Grand Prix mechanics have a tough time lugging their equipment all of 10 feet out of their transporters into the pits where it stays for the whole weekend, consider the contrast for the works rally service crews. They carry everything with them over 10 days and some 2,000 miles and, on the Monte, are driving day and night over some of the toughest roads in Europe in the worst winter weather.

For the 1968 Monte, for example, there were some 40 people involved, travelling in a dozen vehicles carrying some 730 tyres and 550 gallons of fuel to set up some 42 service points as far afield as Dover, Boulogne, Brussels, Madrid, Belgrade, Trento and Athens.

The logistics of the Monte service schedules were detailed in a thick-bound ‘Bible’ which ensured that every member of the team, whatever their responsibilities, not only knew what they had to do but were also aware of where everyone else was stationed and what they were doing. This, of course, was before the era of the mobile phone and where today team managers and service chiefs hover overhead in helicopters. In an emergency or a last minute change of plan the mechanics were expected to use their initiative to the team’s optimum advantage.

A good haul of Tulip Rally trophies – (left) Juliene Vernaeve, Timo Makinen, Peter (with Team Trophy), Mike Wood, Paul Easter and Henry Liddon

One of the service crews’ most important responsibilities was to carry out the refuelling of the works cars, for there was often neither time nor the facility for them to refuel on the road. The Team pioneered the use of large ex-military four-gallon rubber bags which looked like giant hot water bottles. These were immensely strong, easy to carry and stow in odd places. On the ’68 Monte the crews distributed some 550 gallons in a manner which certainly would not comply with today’s Health and Safety Regulations!

Joining the team for the Monte were the ice note crews who would play a vital role in the team’s success. Experienced former team drivers and co-drivers (and some lucky private owners) were co-opted to drive as late as possible over the key competitive stages before they were closed to traffic. They would take with them copies of the crew’s pace notes and would drive over the stage marking the notes in great detail with the road conditions. They would then return to the start of the stage to hand over their updated notes to the crews and would advise on the key decision as to the most suitable choice of tyres.

And it was the tyre schedule for the Monte Minis which was unquestionably the most complex for any team. For the four Minis on the 1968 event a total of 730 tyres were available in no fewer than 12 different options which makes Formula 1 tyre strategy pretty basic. The team’s flying Finns, Timo Makinen and Rauno Aaltonen, were mainly responsible for the winter tyre technology, gathering experience from Finnish ice racing and snow rallies. While the very patient Dunlop tyre boffins did agree with the theory of all this, there was always some doubt as to the practical advantages – but we felt that if it gave the drivers extra confidence and a physiological boost then it was all worthwhile. Mind you, there were some folk who suggested that even if Makinen was running on bald remoulds he would still be quickest!

The irony of all this was that on the 1968 Monte there just was not enough snow to give the Minis their advantage and they finished a disappointing third, fourth and fifth behind the works Porsches. Who knows – had there been more snow and more downhill sections which suited front wheel drive it could have been another Mini Monte 1-2-3.

The Safari Rally was one of the great classics of the 1960s, one of the roughest and toughest events in the calendar with its high speed sections on rough dry roads to seemingly impassable mud and flooded river crossings. The BMC Team had never made a serious attack on the Safari until 1968 when it was felt that the 1800, now nicknamed the ‘Land Crab’, could be competitive. This was to be a major commitment for us, starting with the transportation of the cars, spares, tyres, wheels and mechanics to Kenya. Inevitably we ran out of time to consider shipping everything (and there were dock strikes and customs problems in Mombassa) so in the end the cheapest and most effective solution turned out to be to fly the whole lot in a charter plane, a Viscount from British United Airways (which jokingly became Browning’s United Airways!).

The Rally turned out to be total disaster with all three cars retiring with major suspension breakages – very frustrating when months of rough road testing back home indicated that the car was strong but proving once again that there is no substitute for competing in the event itself. My personal disappointment was not helped when I got food poisoning, and had my finger crushed in a car door when helping to push it out of a mud hole, all of which resulted in me spending time in a local hospital. I spent most of the time there wondering how I was going to explain another disappointing result to Lord Stokes when we got home.

It was more than unfortunate that the BL merger should have come at this time when our fortunes were at their lowest ebb and our only competitive rally car, the Mini, was clearly coming to the end of its international career. To be fair I was given a roving commission to go and talk to the management of the various divisions about competition potential and, as such, I was perhaps in a unique position within this massive corporation.

The three car 1800 Team failed to finish the 1968 Safari – but we did get some great pictures!

The European opposition were now building-in homologation options into the design stage of their potential competition cars and I could not get across to the people at BL that we had to do the same. And, most important, we had to have a long term competitions commitment. But everyone was struggling to meet production deadlines to tight budgets and, to be fair, they probably did not need the distraction of considering competition options – and they certainly did not welcome this young upstart from Abingdon pushing them for action! Mind you when you start with cars like the Morris Marina or the Allegro there is not much hope!

With our European rally programme dramatically reduced the round-the-world Marathons came along – London to Sydney to be followed by London to Mexico. A good performance on these big budget events was to be vital for the Team.

We pinned our hopes on the 1800 for London to Sydney and all five cars finished with Paddy Hopkirk runner up just six minutes adrift after 10,000 miles. Inevitably the BL management were disappointed – had we been beaten by a Porsche they could have understood, but not a Hillman Hunter!

Moving on a year with the London to Mexico World Cup Rally, it was to be another second best for the Team – this time with the Triumph 2.5pi. Brian Culcheth led the Team home in second place behind the flying works Escort. For me it was back to Longbridge to make excuses for another second best performance.

With growing frustration Stokes reluctantly told me that we could carry on and do what we wanted providing we won and that we did not spend any money! So as a last ditch attempt to win something with a BL badge on it we built the Racing Rover with a 4.3 Traco V8 engine and took it to the 86 Hours Marathon at the Nurburgring. The monster was the sensation of the event leading all the way for 16 hours until a grumbling prop shaft forced retirement. The Rover was then 50 miles ahead of all the opposition, thundering around the 17 mile circuit needing only one gear change per lap!

I returned to Abingdon ready to report the good news to Longbridge armed with a file of complimentary press cuttings only to find our P45s on our desks, Stokes having decided that the time had come to close the Department.

It was a devastating end to my privileged time of running the Team, clearly the greatest experience of a lifetime. Typifying the anti-Abingdon attitude that persisted at Longbridge at the time was my final policy instruction, which was to ensure that all of the Comps records and build sheets plus the photo library were destroyed. Needless to say the only thing that went in the dustbin was the policy instruction!

Running in the 84 Hour Marathon Mini – two hours non-stop around Castle Combe confirmed that I would never make a racing driver

MG Car Club

MG Car Club