MGB to the Andes

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

This week we travel back to April 1967, and a Safety Fast! article written by Tom Oleson – an American that lived in Peru at the time, who decided to take on the incredible task of driving his MGB up the Andes.

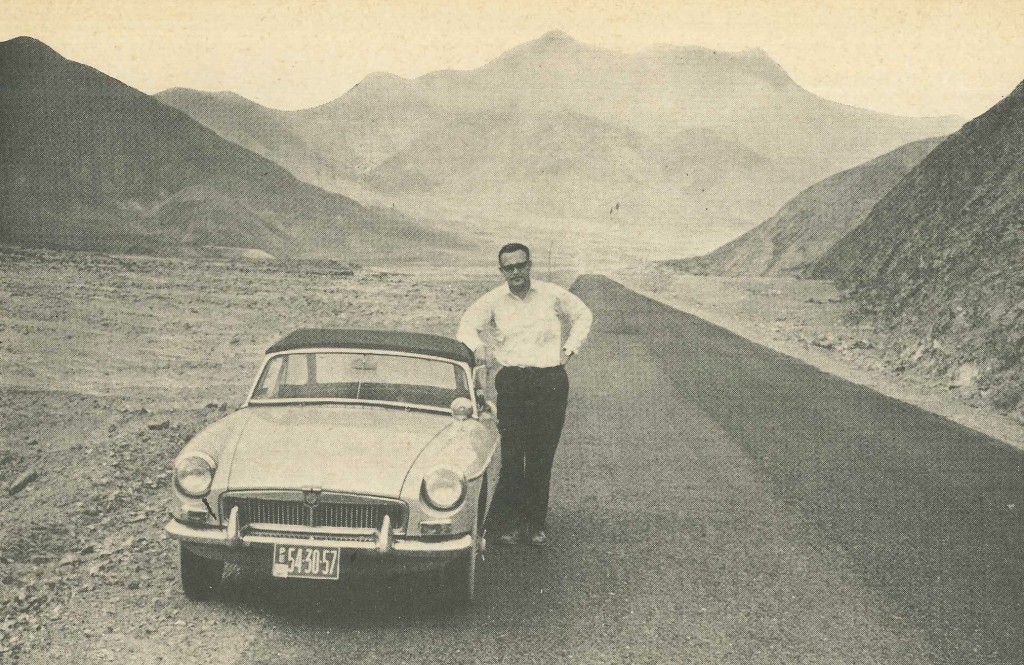

The author with his ‘MGB’, stretching his legs after the long descent from the 14,000-foot Callan Pass. This was the first good piece of road on the whole journey.

The author with his ‘MGB’, stretching his legs after the long descent from the 14,000-foot Callan Pass. This was the first good piece of road on the whole journey.

In January of 1963 I purchased one of the first MGBs to arrive in Peru. The price then was £1,350, and has now increased to £1,800 owing to higher duties, which probably will soon be raised yet again. Having owned a 1953 TD and a 1956 MGA, as well as several other sports cars, I was delighted at the many improvements I found in the new MGB.

That August a friend from New York came to visit me, and we decided to take a trip in my new MG The first day we drove to the city of Trujillo, fourth largest in Peru with a population of 120,000, 360 miles north of Lima on the Pan-American Highway, which is asphalted and in good condition for most of the way.

This is the only north-south route through Peru, and it passes for the most part through some of the driest desert on earth, relieved only by occasional cotton and sugar haciendas, fed by the few small streams which come from the Andes a few miles to the east. Just north of Trujillo are the fascinating adobe ruins of the ancient city of Chan Chan, seat of the Chimu culture, which was subjugated by the Incas about 150 years before they in turn were conquered by the Spaniards.

Driving hour after hour through these ruins (slowly, as they are in complete abandon, with no access roads), one could-see why this city is thought to have been the largest in the world in the middle of the 14th century, with a population of perhaps 250,000.

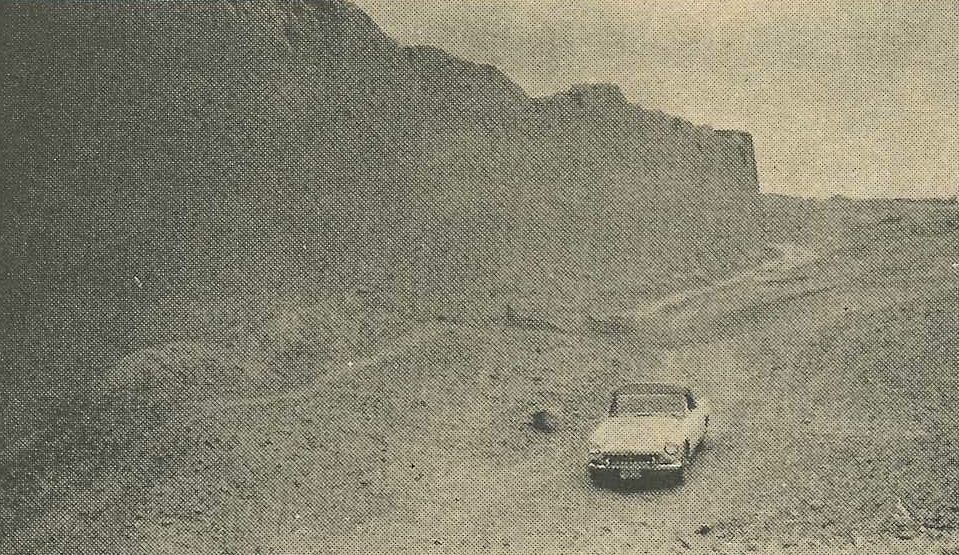

The summit of the Callan Pass is 13,861 feet above sea-level and the traditional cross marks the highest point.

The summit of the Callan Pass is 13,861 feet above sea-level and the traditional cross marks the highest point.

A day later we drove 75 miles south to Chimbote, chief centre of Peru’s most important industry—the production of fish-meal. The following morning we put the MG on the train for the 85-mile trip to Huallanca, high in the Andes, there being no road at this point. I’m sure that Hannibal’s elephants caused no more surprise than did my MG at the railhead almost two miles high! When we had driven a few miles from Huallanca we could see why, as the road climbed through Canon del Pato.

We went through 42 tunnels in about 15 miles, the majority strewn with rocks. Climbing continually in low gear because of the rough road, the MG overheated once or twice, but we welcomed the opportunity to stop. The area of Peru we were about to enter, called the Callejon de Huaylas, is one of the most beautiful in the country, if not the world. A long and beautiful valley about 5 miles wide, 10,000 ft. high, is guarded on the east by the Cordillera Blanca, 20,000 ft. and higher for the most part, and on the west by the Cordillera Negra, 15,000 ft. high.

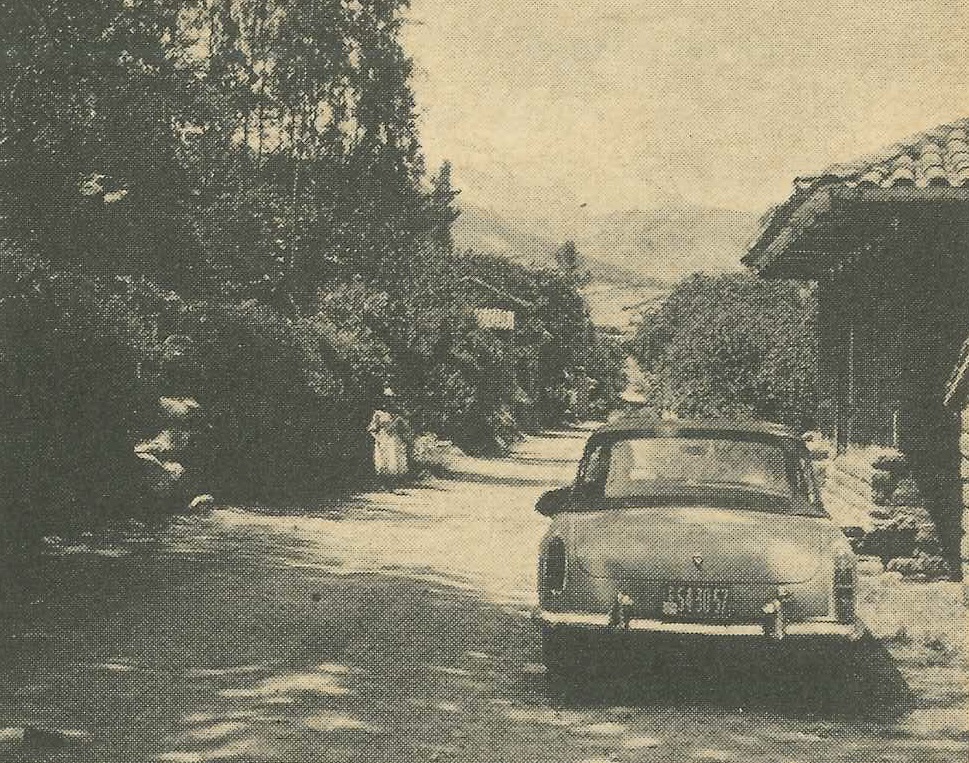

Despite the altitude, the sun is warm and the vegetation tropical. Our goal that day was Monterrey, a small resort town a few miles north of Huaras at the south end of the valley, about 75 miles from Huallanca. The road was so rough, however, that the limited ground clearance of the MG necessitated rather slow progress, so we stayed the night in the small Indian village of Cards, having made but 25 miles that afternoon.

We found simple but adequate lodging for the equivalent of 5 shillings each. We feared a bit for the MG, as there are no garages in Cards, and the wire wheels were fascinating to the Indians of the village. The next morning, however, we looked out of the window to find the car intact, wheels and all! As the hotel had no water supply that day, we washed our faces and brushed our teeth at a fountain in the main square, only to read in the papers when we returned to Lima that a typhoid epidemic had just broken out in Cards!

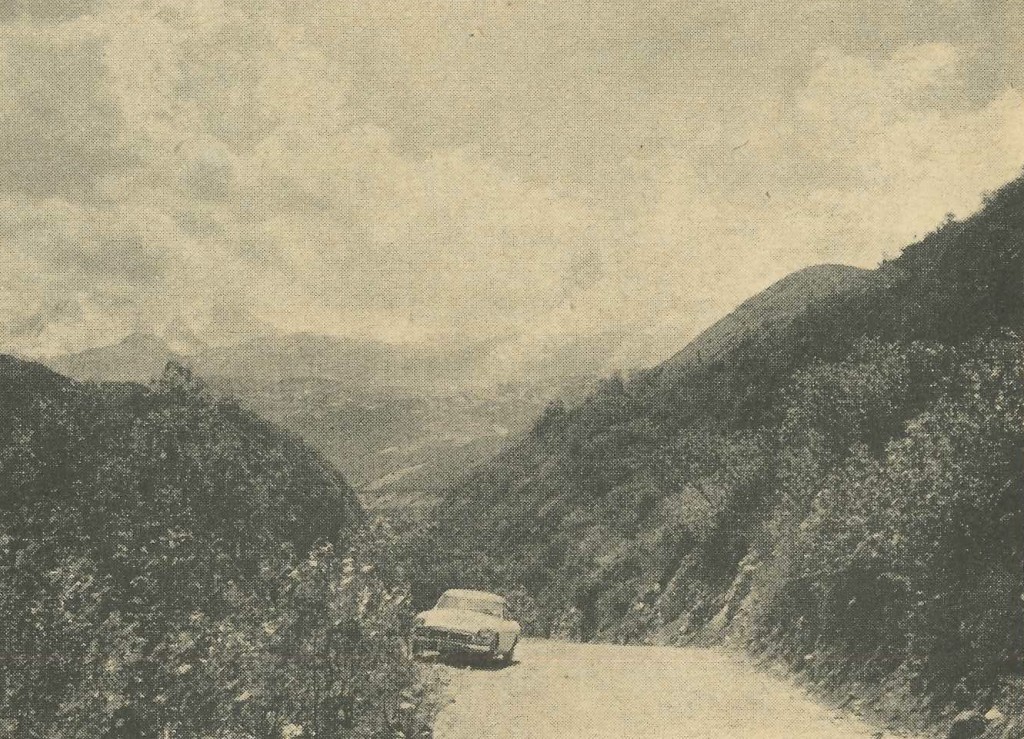

On way up below the scenery is magnificent and the road rough and dusty. The descent on the other side was much narrower and rougher.

On way up below the scenery is magnificent and the road rough and dusty. The descent on the other side was much narrower and rougher.

That morning we explored the village, and left at midday to drive south through the valley. It was a beautiful sunny day, with the mountains gleaming on either side. We passed the boulder-strewn site of Ranrahirca, which had been a town of 6,000 people before it was completely buried in 1961 by an avalanche from MT. Huascaran, highest peak in Peru (22,199ft.) There were very few survivors. On the flank of the mountainwe could see a grey stain where the side of a lake had given way, causing the disaster below. We reached our destination that afternoon, and spent the next few days exploring the valley, including a trip to the foot of Huascaran, where there is an emerald green lake surrounded by orange coloured trees!

This range of mountains was visited not too long ago by some of the members of the first team to climb Mt. Everest, and they found the Andes here equally as impressive as the Himalayas. Not wishing to retrace our steps, I was apprehensive as to how we could leave the valley. To reach the Pan-American Highway on the Pacific Coast 50 air miles to the west it was necessary to cross the Cordillera Negra (Black Range).

The road in the valley had been poor, but the passes through the mountains were said to be much worse. Of the two, we chose the shorter one, although it was little travelled and said to be in bad shape, but passable, Our guidebook said: ‘Callan Pass, 13,861 ft. (summit of Mt. Blanc is 15,771), 65 miles, 8 hours.’ Hoping to avoid oncoming traffic, which is often a dangerous experience on the Andean paths that are called roads, we left very early.

The first hour, climbing to the top of the pass, was great fun, as the precise handling of the MG on the fairly wide road (dirt, like almost all roads in the Andes) made for rapid progress. When we reached the cross that marks the top of all Andean passes, we had become rather overconfident, as the road going down very soon was little wider than the MG, extremely dusty, and littered with rocks. The middle of the road was so high that I had to drive with one wheel on the crown and one either in the right or left rut, whichever was the least rocky.

North of Trujillo are the extensive ruins of the ancient city of Chan Chan, believed to have been the largest city in the world in the 14th century.

North of Trujillo are the extensive ruins of the ancient city of Chan Chan, believed to have been the largest city in the world in the 14th century.

Soon dust had penetrated to every corner of the car, and our appearance was peculiar indeed! This and the constant need to avoid rocks in the road left me utterly exhausted when finally we reached the foot-hills, coming by surprise on a few miles of beautiful straight road.

My fears that the MG which had not been specially prepared in any way for the trip, might have suffered some damage, proved groundless as we sped at high speed along this deceptively fine road. There were a few more bumps to come before we reached the Pan-American Highway, but apart from a flat tyre-the only mishap of the entire trip; meaning our journey back to Lima was uneventful.

The next weekend we headed for the Andes again, driving 98 miles east of Lima to what is said to be the highest road and rail point in the world—the Anticona Pass, 15,693 ft. above sea level. Again the car performed faultlessly, and I believe I can claim the altitude record for the MGB!

An overnight stop was made in the Indian village of Caras.

An overnight stop was made in the Indian village of Caras.

I am still enjoying my car, which now has done about 20,000 miles. Despite the rough treatment it has been subjected to (and sometimes I think that the pot-holed streets of Lima are worse than any mountain road), the original tyres seem hardly worn, and the car looks and runs like new. The service for BMC products here in Lima is excellent and cheap, and the car (8.2:1 compression ratio) seems to run well on the best available gas, 92-octane. Prior to the MGB sports car racing here, it was dominated by Alfa Romeos, especially several late models of the Zagato bodied version.

Last year however, the Alfas were beaten, and an MG like mine took the title. T.O.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club