MG on the job 1936-1940

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

This week’s feature goes into depth about the use of MGs in the police-force and driving courses from 1936-1940. It was written by Allan Scott, and first published in Safety Fast! back in July 1984.

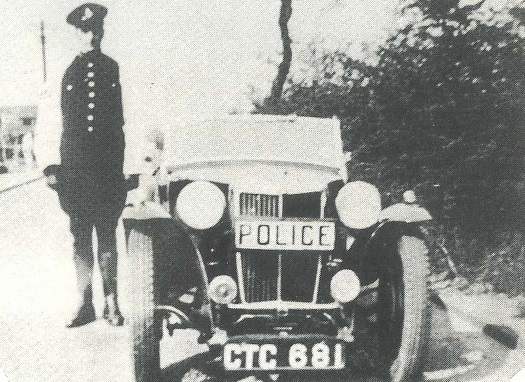

In 1937, the trumpet shaped public address system was introduced to give advice to pedestrians. Tried in Parliament Square it is not recorded whether the public appreciated having their mistakes broadcast. The trumpets were removed at the end of 1938. Not the wireless aerial under the running board. (Photo courtesy of British Motor Industry Heritage Trust)

In 1937, the trumpet shaped public address system was introduced to give advice to pedestrians. Tried in Parliament Square it is not recorded whether the public appreciated having their mistakes broadcast. The trumpets were removed at the end of 1938. Not the wireless aerial under the running board. (Photo courtesy of British Motor Industry Heritage Trust)

During the 1920’s and 1930’s, this country was subject to a great vehicle population explosion as the motorcar became available to the general public.

The roads of Victorian Britain became overcrowded and unsuited to the increasing speed of motorised traffic. The increase in fatal and serious accidents increased at an even greater rate than the traffic density. There were 1,000,000 cars registered by 1930. The Police as keepers of the peace had been preaching ‘Road Safety’ in schools since 1906, but the pedestrian and vehicular public had scant regard for each other’s shortcomings.

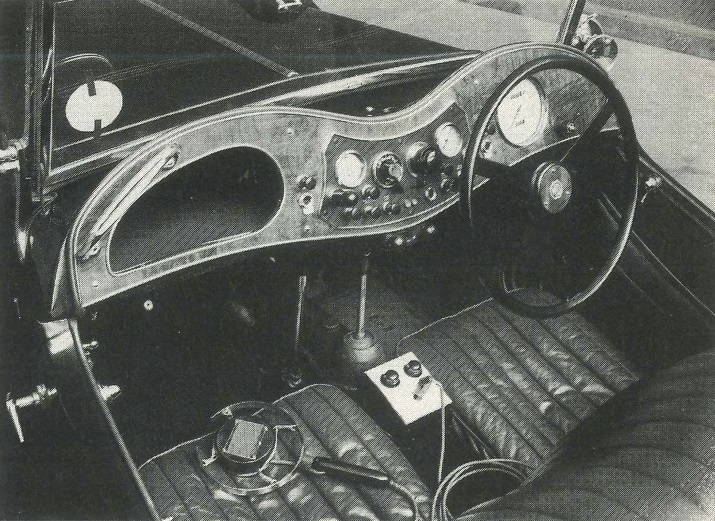

Microphone for public address and wireless channel control. This is BRX 166 and has push-pull switches and adjustable steering column. (Photo courtesy of British Motor Industry Heritage Trust)

Microphone for public address and wireless channel control. This is BRX 166 and has push-pull switches and adjustable steering column. (Photo courtesy of British Motor Industry Heritage Trust)

Eventually, the accidents reached a level which became a Parliamentary issue. The result was the 1930 Road Traffic Act. The most immediate change was the introduction of the Driving Test. The blanket limit of 20 mph was lifted and 30 mph limit introduced. The Police were expected to enforce the new laws and Lord Trenchard formed a committee in 1931 to consider the whole question of Motor Patrols. The Police coped as best they could, whilst the committee drafted new proposals which Lord Hore Belisha, notable road safety reformer introduced to Parliament.

The 132 Road Traffic Act permitted verbal warning to be issued by the Police, rather than immediate prosecution. The Police had realised that the 30 mph limit made virtually every motorist a criminal. The reaction against the Police was very great and public relations became very bad, because they relied very heavily on the public for information and support.

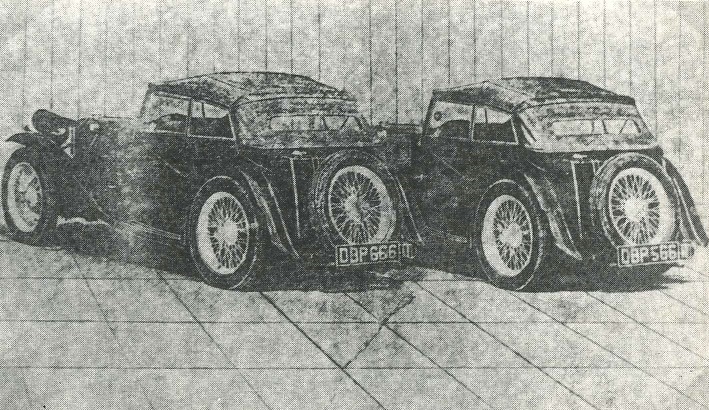

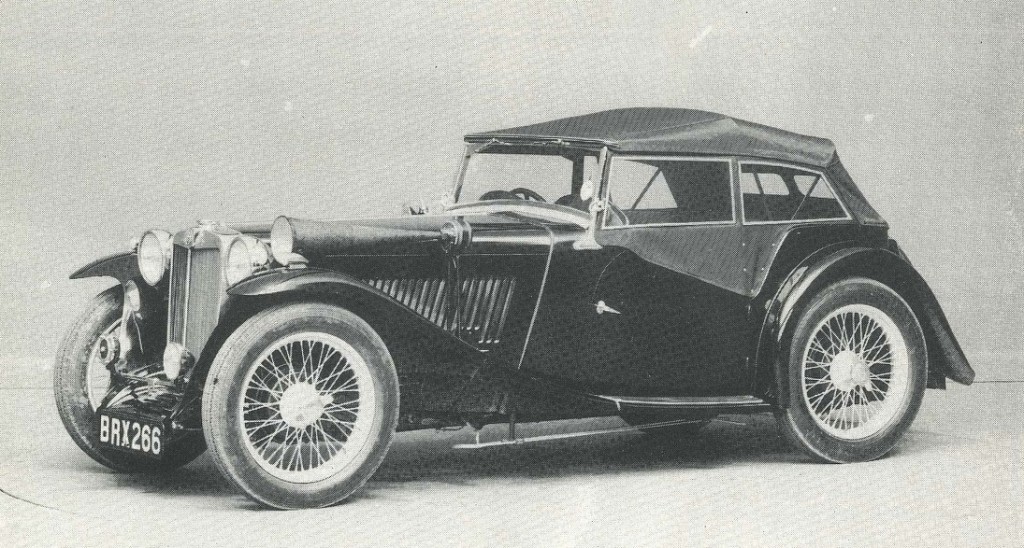

Two MG TAs awaiting collection at Hendon by Sussex Police. These two are VA engined, 1938. (Photo courtesy of Hendon Driving School)

On the roads, the Belisha Beacon, the Traffic Light, and the Roundabout came into general use in 1931. The committee now chaired by Mr H D Morgan OBE also gained Major Tomlin Assistant Commissioner and Lord Cottenham. At their recommendation Lord Trenchard persuaded Sir Malcolm Campbell to test some Police drivers. It was realised that they must be seen to be better than the public, to set a good standard and become a credible law keeping force.

The Police, like the public, were untrained although the driving standard was fairly high. The accident rate at that time was one per 8000 miles. The Tomlin committee was constructive; almost all of its recommendations were adopted. Also it was realised, reliable vehicles with predictable handling characteristics were required. A test site was created at Hendon which, being within the Metropolitan Area and close to the Home Office could be easily controlled.

Up to this time the Home Office contented itself with ‘Notes of Guidance’ to Chief Constables on choice of vehicles and on the implementation of motor patrols. It now issued a formal ‘Statement of Requirements’, summarised thus:- ‘Cars to be Black, Upholstery to be Oxford Blue, Speedometer to be calibrated, Steering column to be adjustable, Electrical switches to be ‘Pull on’, ‘Push off’, Fuses to be fitted to each lamp, Engines had a separate requirement which specified 82 Octane Fuel and Steel Sump’. The Home Office sponsored other developments. In 1934 the ‘Wireless Scheme’ provided Morse communication from car to station.

The country was divided into 75 areas, each of which was equipped with a car or van fitted with a key transmitter from which reports were sent to the local station. Reports were made direct from the stations to Scotland Yard which kept a 24 hour operations room. Within two years this system was superseded by speech transmission. By 1938 it even extended to the man on the job. The equipment was massive but it could transmit from inside a building.

Servicing was next for scrutiny. Constables were expected to spend four hours a week on routine maintenance and the cars had to be washed daily. Eight garages were set up in the Metropolitan Area for major overhauls. The County forces followed the example.

Hendon was chosen to become the first training school in 1935. Two other schools were established and all three were equipped with cars from the type test scheme. The Home Office then launched a scheme with the help of the press, to contact the public. This was known as the ‘Courtesy Scheme’. The whole of the cost of equipping Municipal Authorities with this supplementary force was covered by Whitehall for a trial period commencing mid. 1937 and ending September 1939.

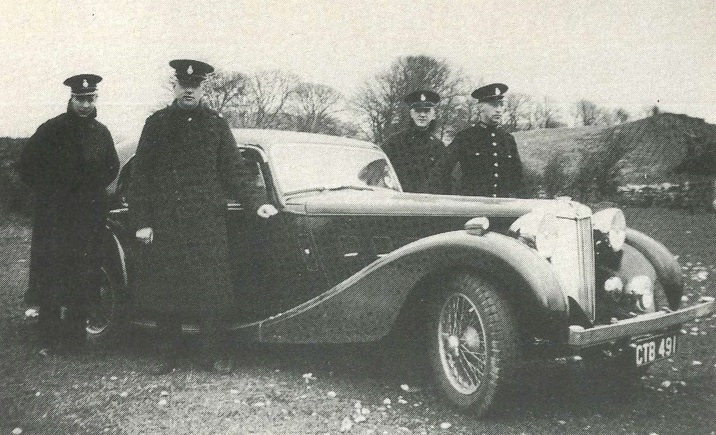

MG SA. Part of the first advance driving course at Hutton Hall in 1937. PC. Gratrix on the right. (Photo courtesy Lancashire Constabulary Museum)

After this, only 50% of the cost was funded by the H. O. MG cars which were in the minority, were chosen. The MG TA was a cheap car at £222 each; they were rugged and had a sporting performance. Hendon had been Police proofing vehicles and they had shown up very well.

The next step from the committee would have been to reduce the number of types to ease maintenance, but war intervened. Hendon driving school had been established on 7th January 1935, running basic courses and maintenance classes. Early in 1937 an advanced driving class was ready to qualify a nucleus of instructors, 24 in all, eight to each new Advanced Driving School. A system of training was devised by Sir Phillip Game and Lord Cottenham which allowed trainees to teach and qualify each other to give advice on safe driving.

They raised the standard of driving to a new level. The manual was eventually published as Road craft in 1961. The course headings were: Observation, principals of safety, correct use of steering, acceleration, gear changing, breaking, and correct use of horn and Mirror. The last item was considered most important and emphasised the need to take up a position of safety on the road without inconveniencing other road users.

The course took four weeks, at the end of which each school was provided with eighteen cars at Home Office expense. The cars chosen, gave the students an appreciation of fine cars and since the mount was changed continuously, was a searching test of ability. On 7th July 1937 the eight instructors of the school at Hutton Hall Preston were ready to handle the first course of 21 candidates. Final selection was conducted by Lord Cottenham the Alvis Team driver, who personally tested the entire group. He passed 16.

In October a primary course for those with little or no skills commenced at Hutton Hall. The cars used by the schools were all types used in service and some fine cars bought second hand. Hutton Hall was equipped with Morris 12, Wolseley 18, MG SA, Triumph Gloria, Railton, and Chrysler Airflow, saloons every one. Chelmsford received, Alvis 25, Armstrong Siddely Humber, MG SA, Lagonda Rapide, Standard 12, Ford V8, SS 2.5 litre, and Talbot 10.

When the schools were fully commissioned, Lord Cottenham himself provided three Lagonda Tickford Tourers. One was presented to each school. Hutton Hall used theirs on the skid pan once and then rescued it for use as the final advanced test car, a use for which it was well suited because of its difficult gearbox. The car survives today in this role. Chelmsford used their car extensively on the skidpan, which cost them dearly in broken spokes.

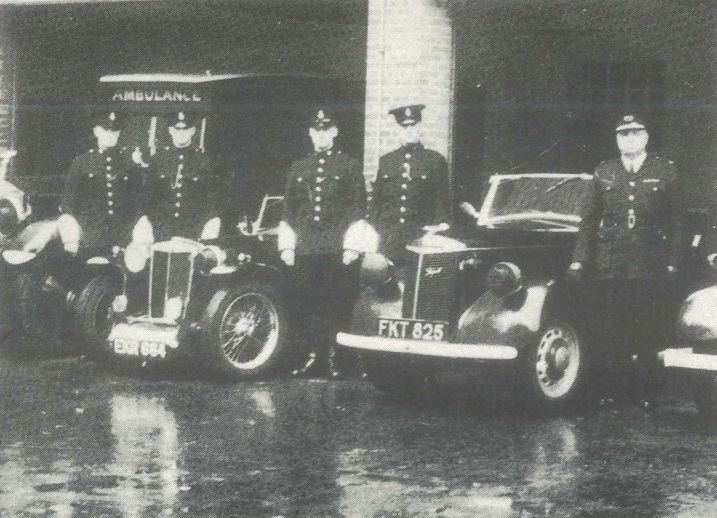

1939 Kent Emergency Services — Ambulance, Police, Fire. (Photo courtesy of Kent Constabulary)

This indirectly benefitted MG, who took note and provided the bulk of their Home Office orders with centre spoke wheels. Inevitably the methods of training at the schools varied, whilst still adhering to the basic manual. Hendon was thought to place too much emphasis on speed. Certainly trainees were encouraged to push the machinery to its limit, imposing strains they would never place on their own vehicles. Of course the school could always draw another one from stores.

Trainees found the cornering method taught hair raising and dangerous. To save time making a turn they were told to observe the rear, select a gear, draw close to the white line in the road centre and exit the corner using the nearside kerb as a clipping point. Effectively this was a racing line and very quick. However the test track was open to two-way traffic and the right hand bend was approached from the extreme nearside, swinging hard to the road centre line for exit.

Lord Cottenham had introduced a microphone into the cars, through which the drivers were expected to give a running commentary explaining their actions. The bends were blind, so the commentary must have been worth listening to, during the ensuing panic as the cars met in the bend. The schools operated up to the outbreak of war, when all courses ceased except for the

primary. This course was expanded to train drivers for the Constabulary, Auxilliary Fire Service, -Ambulance Brigade, and service men and women throughout the war. The Home Office having provided the Police with a corps of trained drivers, selected vehicles for patrol use and launched the ‘Courtesy Cops’ in 1937.

The initial batch of thirty cars and sixty men were attached to local stations in Lancashire. This was to be the single biggest deployment of the MG TA, where the cars were sent out to meet the errant public. The idea was to implement the Tomlin committee’s suggestion to warn, guide, and instruct rather than prosecute as exactly as possible, and monitor the results over the period July 1937 to Sept. 1939.

The Police called these crews the ‘Flying Squad’ except in the London area where the Flying Squad already existed. The cars were to be found where the public existed in greatest numbers. This meant sporting occasions, duty on the notorious East Lanes road at Bank Holidays; town centres point duty, and patrols on main trunk roads. Other Counties adopted the T Type, Berks, Derby, Hants, Kent and Sussex. This intensive exposure revealed some defects.

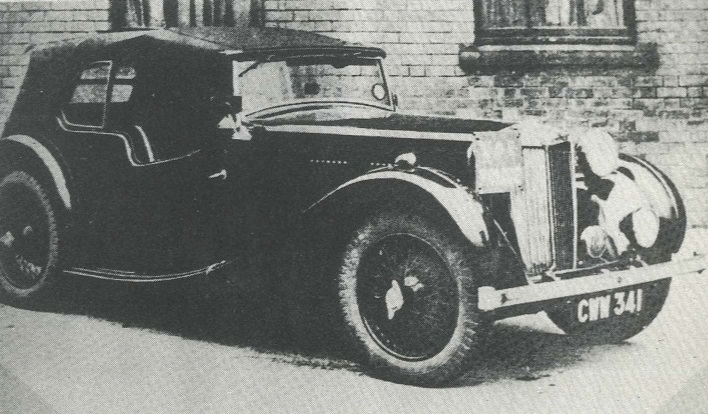

MG VA Tourer, 1940 Wakefield. (Photo courtesy of West Riding; Yorkshire, Wakefield, Museum)

The brakes were suspect and barely adequate, marginal at best. The side spoke wheels were flimsy and had to be replaced by centre spoke pattern at the end of 1937. Despite its sporting pretensions, the car was not fast enough for pursuit. At the end of 1937 some cars from Sussex, Kent and Lancashire were returned to Abingdon to be examined for wear in accordance with the Type Test requirement.

At least two of these cars emerged from the works with VA engine being sent first to Hendon and then collected by the Sussex Police in April 1938. The TA in service nobly upheld its reputation being cheap and reliable it remained in service until 1946 and in one case 1948. The Yorkshire Police chose the VA to catch its local speedsters. The cars were tourers, and these also remained in service throughout the war mainly on air raid warning duties.

The last service example still resides as an exhibit in Wakefield Driving School as a sectioned model. I am told that it was cup up by trainees as an exercise using broken raw hacksaw blades. The Police in training used the SA Saloon at the driving schools. It had a fine reputation as a well-balanced, good handling car which was eagerly sought after for slippery driving conditions. The cars were slightly underpowered but this was rectified by fitting the larger 2322cc engine.

The compression ratio was slightly raised to take advantage of the 82 octane fuel available to the Police. The Metropolitan Police used the SA extensively calling it a Magnette in their documents. It was a strong contender to become the standard saloon for the force, but it was rivalled by the Wolseley 18 which had a larger body and better front suspension. The capacious body allowed bulky Policemen to exit the car more rapidly and the large boot easily accommodated the bulk of the wireless easily.

The WA also got in on the act being used in places as widely displaced as Glasgow and Brighton. All MOWOG cars were popular with maintenance men because of the common spares policy which foreshadowed the recommendations of the Tomlin Committee. This stood the company in good stead for many years. Engine maintenance consisted of removing the cylinder head at regular intervals of 10,000 miles for attention to the valves. The engines of the TA, VA, SA, WA, were capable of very high mileages of the order of 100,000 miles the valves were attended to regularly and the oil was changed every 1500 miles.

This reflects on the quality of the oils and fuels available at that time. In contrast the TB which followed the TA into service nearly wrecked the MG reputation for good until Laystall liners were fitted to extend the bore life. The TB was the last model to leave the factory after war broke out; the last pair was collected by the Sussex Police in 1940. The “Flying Squad” was seconded for duty to relieve local Police of traffic duties. The superintendent could thus deploy his local men to fight crime.

MG TA 1937, Pc. C. Gratrix taken by Mrs Gratrix. (Photo courtesy of MG TA 1937 July, Pc. 807 Cecil Gratrix)

There was a tendency to try to draft the Squad onto general duties. The crews fiercely resisted this takeover bid and attempted to commandeer their cars failed. They had their own level of duty which combined Traffic and Police work. Patrol cars in all Lancashire towns plus Birmingham, Newcastle, and the Metropolitan area had ‘Stop and Search’ powers. The only County empowered to do this was Hereford.

If a vehicle was suspected of carrying stolen goods it could be searched without any delay. This greatly improved the coverage provided by the law. Standing orders were that hood would remain furled regardless of weather. It was not unknown for Policemen to fall flat on their back allowing a criminal to escape. The Police were

very philosophical about this because they regarded crime as a habit and there would always be another chance. Even so, policemen were obviously a very tough breed of men. The effectiveness of the Flying Squad on the job was proved beyond doubt. The reduction in serious and fatal accidents from their introduction in 1937 to the outbreak of war in 1939 was 45%, whilst the increase in criminal arrests was 40% after the outbreak of war the general public continued motoring for a white until fuel and tyre shortages put a stop to it.

Even then some of the lucky few motored on. There were drawbacks of course such as being labelled ‘black marketer’ ‘squander bug’ or ‘enemy agent’. At best you would be investigated. Night shifts became regular and this combined with the blackout made things very hazardous for the pedestrian.

It was certainly wiser to jump in a hedge or ditch rather than be run down by an ill lit vehicle. The police were conspicuous by their absence. The police patrols duties were changed; air raid warnings were now a priority as was guidance of the inevitable night convoys of food and munitions. There were night patrols, but these were to clear the roads of parked cars, unceremoniously bundling them into alleys and gardens.

Traffic parked on main roads had to face in the direction of the traffic to enable the cars to comply with the lighting laws they were fitted with the Hartley Mask, side lights were masked down to a hole size of 3/s”, differentials were painted white and illuminated by a small bulb mounted under the rear of the car. Wings and bumpers were painted with a rather corrosive luminous paint outlining them in white.

One of the original courtesy cops ready for patrol in standard uniform of the time. (Photo courtesy of Lancashire Constabulary Museum)

Since the road signs had been removed and convoys spent the night blundering round unlit towns, pavement edges were painted white at corners marking the through routes. The police had to plan the routes and escort them safely through. Despite this activity the Police reduced their road mileage by 50%. This enabled them to continue until 1942 when all fuel supplies were restricted and pool petrol was introduced.

I would like to thank all the Policemen active and retired who helped in the preparation of this article. Also the Police forces of Hampshire, Kent, Lancashire, Yorkshire and the Metropolitan Area, the driving schools at Hendon, Chelmsford, Preston, and Wakefield. Further information came from the National Motor Museum Beaulieu and the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust and members of the MGCC without whose background help the article would not be possible. A.S.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club