The Second World War Two and MG – How the car manufacturer helped win the war.

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

MG may be about cars to most, but how they helped during the war did not go unrecognised – with some people regarding the work in Abingdon being the pinnacle of the company’s successful history.

The following excerpt comes from ‘MG War Time Activities’ by George Propert, former General Manager at MG. The original 59 A5 page document was re-edited by club secretary Colin Grant so this incredible information could be shared with enthusiasts worldwide. The full version is available to purchase through the club’s online shop by clicking here.

At the outbreak of war, it was obvious that motorcar manufacture would have to cease, and the Government would need the factory capacity for essential war work.

Having this clearly in mind, we commenced to clear the factory. This was rather a sad job because it had been planned and built to suit our particular productive needs and it seemed that in pulling out the major plant, we were destroying any possibilities of making M.G. cars, and goodness only knew when we should be able to start up again, but “needs must when the devil (Hitler) drives” and we set about the job.

It was soon clearly obvious that if we were going to handle major war work, the first thing would be perfectly clear factory floor space. So our expensive paint plant and all other motorcar producing equipment was removed and put into cold storage.

This all sounds relatively easy, but even the breakdown of the plant brought its problems because to store the complete factory plant meant that we had to get a premises practically half as big as our own factory and this did not seem practicable, particularly in view of the fact that in clearing the factory we should also have to clear many hundreds of tons of extremely valuable motor car parts, which included the service stores material and all the left over production material, the least easy of which to store were the many hundreds of chassis frames.

Fortunately we were able to acquire a very dilapidated dis‑used local factory, which at some considerable expense, we were able to put into suitable condition as a Stores. So at the end of 1939 we found ourselves with a completely empty factory and no work to do, because our idea that as soon as the works was empty, the Ministry would be rushing a job along to us was quite erroneous.

This was very understandable because the Ministry had to get themselves sorted out and it is quite conceivable that they had quite a vague idea at that time what they would need. In any case, to get any sizeable job under way, a good many months are required. However, we had crossed the first bridge and stood ready. Prior to this we had been taking all sorts of enquiries into the possibilities of acquiring a contract for this or that work, but now it became a job of major importance. Because we could not stand still with an empty factory at such an urgent time of need, our Managing Director and the General Manager made it their personal job to scour the country for suitable contracts.

A good deal of this time was spent almost literally sitting on the door step of the Ministries concerned. Looked at from this distant date, it is almost amusing to think of the kind of job we were prepared to have a go at. The only thing that mattered to us then was that it should be a job of work directly needed by the fighting men. The writer well remembers on one occasion very, very seriously investigating the possibility of bridge making.

It was in actual fact, although we did not know it at the time, the birth of the Bailey Bridge*, and although we did not undertake this work, it illustrates how keenly anxious we were to get our teeth into an important job. Aircraft rotating turrets and guns too, came into the picture, but despite all the energetic efforts, it was some time before we got started.

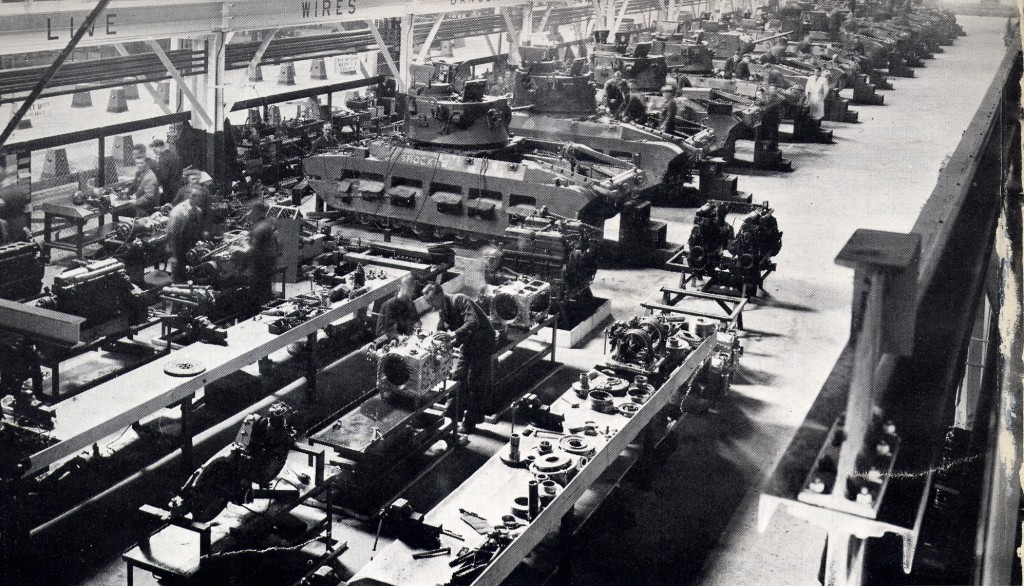

The real start was made with the overhauling of light Armoured Track Vehicles and in due course throughout the years we blossomed out from this minor start to major Tank manufacture and we have had, as the following records show, an enormous variety of Tank jobs. Having seriously started on Tank work, quite unexpectedly an aeroplane contract came our way, the Parent Company having in mind, we assume, that as we were builders of really high-class motor cars, we could successfully handle aircraft.

Little did they know at that time that our knowledge of aircraft work was just nil. It is quite true that if we saw something in the sky we could safely say it was an aeroplane, but as for knowledge of the detailed intricacies of production, this was a closed book to us.

The days that followed when we got hold of some of the drawings were simply terrific. Had it not been for the fact that a number of the senior staff were such grand people who were prepared to have a go at any job, however difficult, and once started never give in, I doubt very much if we should have been brave enough to tackle this, our first aircraft production job.

As it turned out I feel we can be forgiven for boasting about it. We succeeded where several other much bigger manufacturers failed and in the end we had to clean up all their failures and were entrusted with the building of every unit for this particular marque that ever went into the air.

Coincident with this hectic struggle to get aircraft work planned and production really under way were constantly picking up newer and later type Tank models and at the same time altering and adjusting the facilities of the works to meet all the new demands. It was no easy matter, and at times the obstacles appeared to be almost insurmountable, but every senior in the works had the will to win and all the difficulties, mountainous as they sometimes appeared, were ultimately surmounted.

Apart from these major activities, an enormous amount of work was being put into the development of a Press Shop which was called upon to handle many hundreds of different types of Tank Stowage for the Ministry of Supply, work of a some what heavy nature, and in amongst it, various details of light equipment for the Admiralty and special light alloy work for aircraft.

No praise is too high for the ingenuity, which was displayed in this particular section in the creation of special tools, processes and various devices, which ultimately enabled us to meet demands from the Ministries, demands that could not be catered for by the larger manufacturers.

It has oft‑times struck the writer how very true is the old adage that `Necessity is the Mother of Invention’, because jobs of work were put into this section which at first appeared to be entirely outside its scope, and it is really amazing when people have the real will to do the job, how by some means or another they dig out of the unknown a latent ability which never had an opportunity previously to exercise itself.

It was surprising to see how one successful activity after another threw into prominence the need for further effort and with machined details in terribly short supply handicapping the production effort, the necessity for major increased machine capacity became very apparent.

To meet this demand and almost without a thought as to whether it could be successfully accomplished or not, we created a machine shop at our local stores factory and it was really amazing how the seniors concerned, again with that sheer doggedness to succeed, built up a successfully operating plant which solved the detail hold up problems that had previously handicapped the main production effort.

We ultimately found ourselves at the end of 1941 handling a surprisingly large variety of jobs with every square foot of the factory packed to its limit, and at times, taking a bird’s eye view as it were of the whole set up, the change was incredible. it seemed that in a short space of time we had changed from a works filled with daylight and colour, clean to an unusual degree, well planned, with colourful motor cars moving about in active production, to a works that by virtue of the fact that security measures had made it necessary to have a complete black out with artificial light, looking very different from its previous bright clean self, with hardly room to walk about.

It seemed rather sad at times when one remembered previous conditions in the works, but one felt fortified with the thought that however different one would wish the place to be, we were undoubtedly pulling our full weight in the war effort, and this seemed, if anything, to strengthen our resolution to keep on doing more and more if possible, or burst in the attempt. I think one of the major facts that kept it all so very much alive was that one day there must be an end.

Although in the major effort, we might only be a small cog, the efficiency of our set up must be helping to bring nearer the day when there would be a successful issue to the war and we could get back to our peace time occupation, and now as I write after the best part of six years of intensive effort when we are facing up to even greater problems in the rehabilitation period, with major war contracts ceasing, bringing us face to face with difficulties which again seem almost insurmountable, one has a feeling that having been successful in handling all the problems encountered in the war period, we shall, because the same spirit prevails, be fully successful in solving our immediate problems and getting launched on our post‑war work.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club