How MG helped Ford beat Ferrari

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

By Adam Sloman

Le Mans ’66 is one of the biggest films of the year, telling the incredible story of how Ford broke Ferrari’s dominance at the 24 hours. But what part did MG play in the story?

At its heart, Le Mans ’66 (or Ford v Ferrari as it’s known in the US) is the story of two friends – one world-renowned, in Carroll Shelby, the other a hero to motorsport fans in the know, Ken Miles.

Shelby was the all-American hero – a former World War II test-pilot, who in peace-time turned to motorsport, making his debut in May of 1952 at the wheel of an MG TC. Shelby won his first race, which entitled him to a second, and later that day took on bigger, faster cars from the likes of Jaguar and he beat them, too. He would quickly graduate to more exotic machinery, but it was the MG that cemented Shelby’s desire to succeed on the circuit. “I still had a lot to learn, but I knew how to go fast. The MG changed my life, because from that point forward, I knew I wanted to be involved with racing and sports cars.”

In 1959 he would take an Aston Martin to victory at Le Mans, but shortly afterwards he was forced to retire – a heart condition made it too dangerous for him to compete, so while his career on track had been cut short, a new chapter was opening up for Shelby as a constructor.

Ken Miles’ story could not be more different than that of Shelby’s. Born near Birmingham, in his early years he raced motorcycles, and at the age of 15 became an apprentice at Wolseley Motors. He too fought in the Second World War – Miles served in the Territorial Army, becoming a tank commander, and was part of a unit that fought on the beaches of Normandy on D-day.

Post-war, Miles demonstrated a huge talent for motor racing, competing in Alvises, Bugattis and Alfa Romeos. In the early 1950s, Miles and his wife relocated to California, where he would find work as an MG service manager and he began to compete with the Sports Car Club of America.

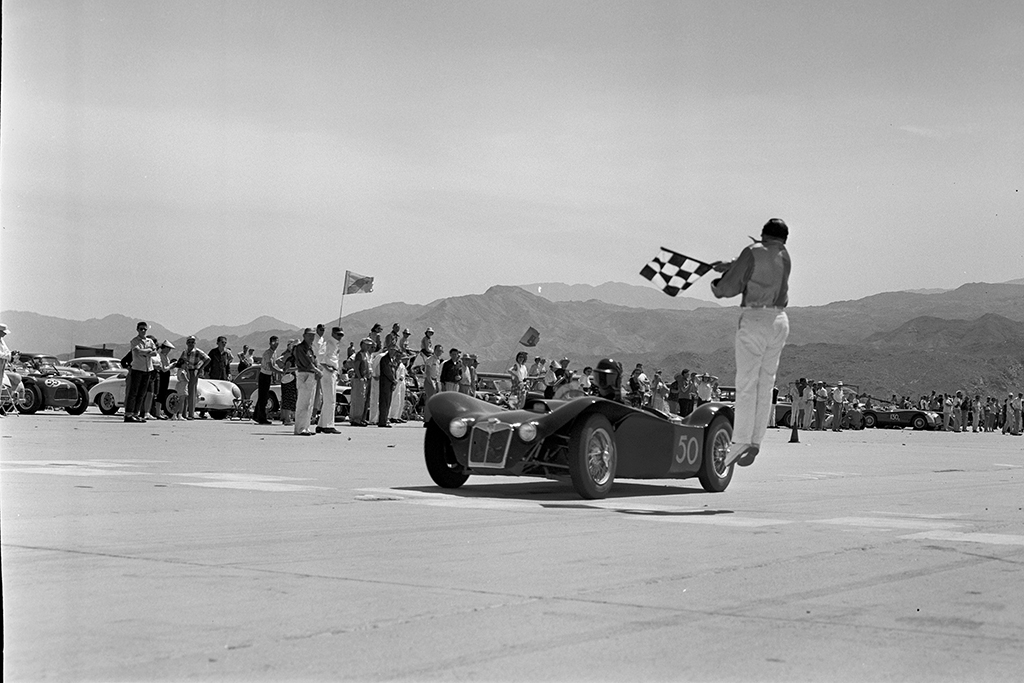

Ken Miles’ most successful MG Special, ‘Flying Shingle’ which he won many a California sports car race in, to the embarrassment of more exotic, supposedly faster, machinery

Miles would build his own car, based on an MG TD. It won its first race and quickly drew attention up and down the West Coast of America. The car was simple, but its simplicity only served to underline Miles’ talent as a driver. Never one to rest on his laurels, Miles set about developing his next car, a more advanced, MG-based special, nicknamed ‘The Flying Shingle’ thanks to its swooping body and low ride-height. It was quicker, smaller and lighter than that first special and his success in the US meant Miles found himself as part of the MG team entered the 1955 Le Mans, competing in EX182. Miles and teammate John Lockett would pilot the MG to 12th place, making it the highest placed MG.

The MGs leaving Abingdon, being driven by the mechanics, and heading to the 1955 Le Mans where Miles et al were to put the EX186 cars through their paces

Unfortunately, the 1955 Le Mans would be remembered not for the MG’s return to the race after a 20-year absence, but for the worst disaster in motorsport history, as 83 spectators and French driver Pierre Levegh died following a major crash.

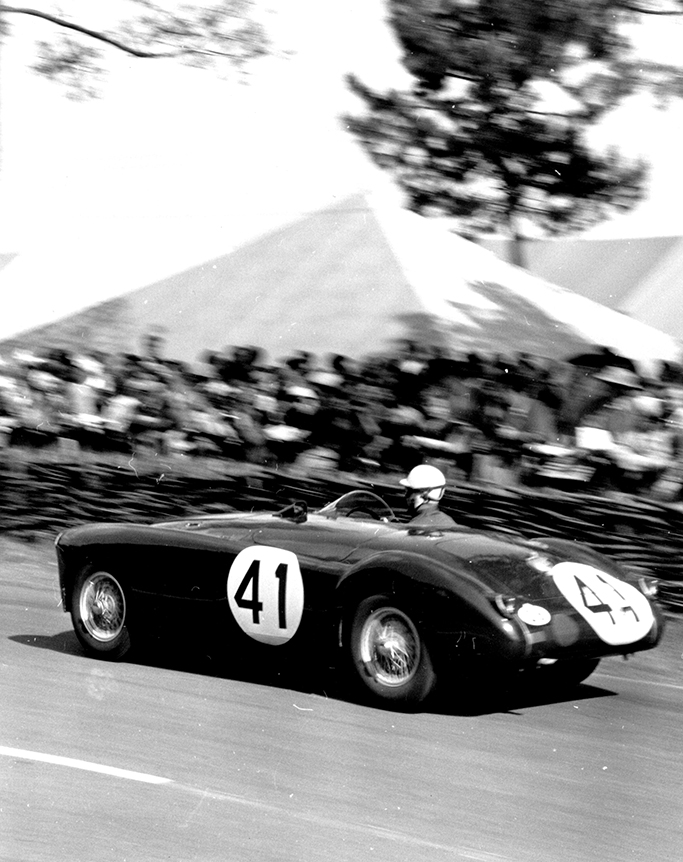

Car 41 competing in the 1955 Le Mans, piloted by K Miles and J Lockett, here flat out on the straight

The events of 1955 led MG to disband its works team and withdraw from racing and Miles returned to the US, and following a difference of opinion with MG General Manager and director John Thornley, moved away from MG. The following year, Miles took MG EX179 to the Bonneville Salt Flats, setting 16 international 1500cc Class ‘E’ records, including 170.15mph for 10 miles and 141.71mph over 12 hours.

His final race in an MG came in the Flying Shingle, in 1956. As the likes of Porsche began to make their presence known in motorsport, Miles moved with the times, competing in a Porsche-powered Cooper special, racing against another icon in MG’s history – Phil Hill.

As the 1950s drew to a close, MG’s focus was on its record-breakers, something Miles felt to be of little benefit, taking to print in the US magazine Competition Press. He believed that MG still had the potential to succeed internationally, but that the marque was held back, constrained by the management of the British Motor Corporation. “The results of high speed or endurance runs are highly predictable,” he said, adding: “The results are in the bag before the car ever leaves the factory.”

Thornley would respond in the pages of Safety Fast!, reminding all that Miles remained a friend before explaining to Miles that the investment made in a decade of record breaking would not support a racing stable for a single season.

Miles clearly had a passion for MG and a desire to see it racing amongst the best, but in the end, neither the budget nor the political will within BMC existed to push MG onto the global motorsport stage and Miles would move.

In the early 1960s, Miles would become lead test driver for Shelby, playing a key role in the development of the AC Cobra. Other work would see him help develop the Sunbeam Tiger, before in 1964 he would take a key role, alongside Shelby, in completing the development of the Ford GT40 – a car in which he would win the Daytona 24hrs, the Sebring 12hrs and, if not for company politics at Ford, the 1966 Le Mans 24hrs.

Tragedy would strike a year later in 1967 when, while testing Ford’s next GT racer, Miles’ car flipped, crashed and caught fire. He was 47 years old when he died.

Miles would be inducted into the Motorsport Hall of Fame in 2001 and is considered one of the founding fathers of US road-racing. His contribution to motorsport should not be forgotten and he deserves to be more widely remembered than he has been – hopefully his and Shelby’s story, told so well in Le Mans ’66, will change that. However his achievements before the 1960s should be noted, too, as should all he achieved behind the wheel of an MG.

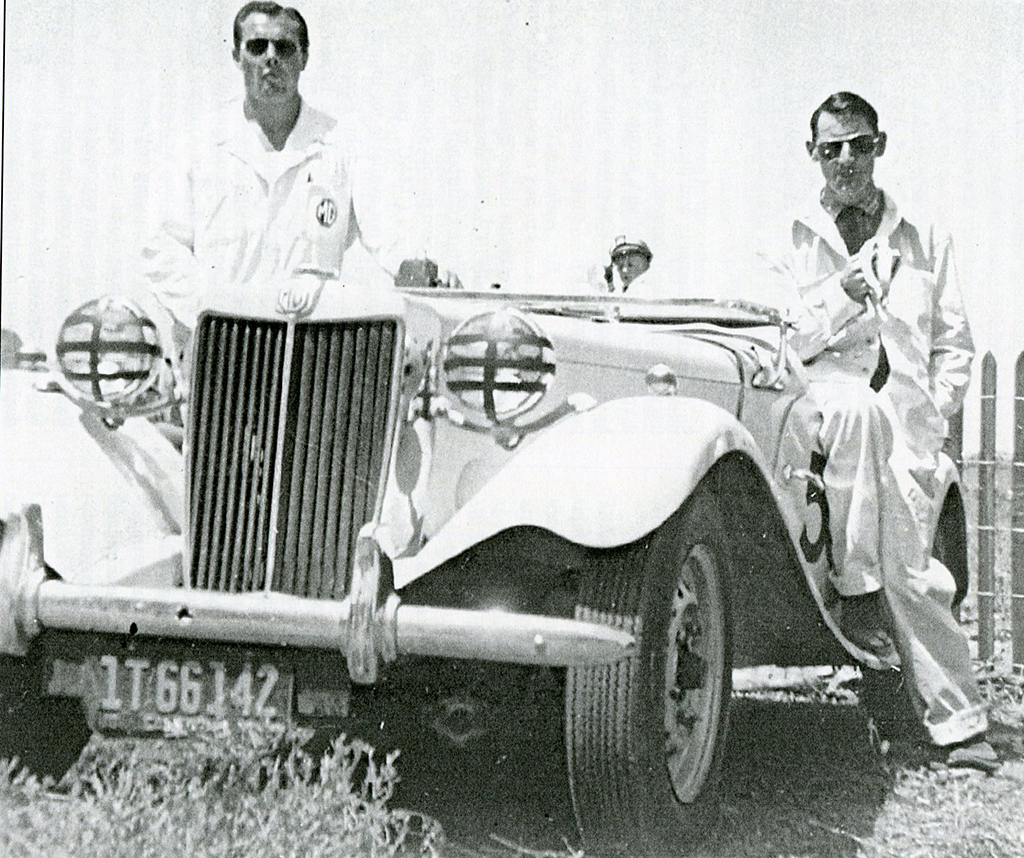

Gordon Whitby (left) and Ken Miles (right) with his stock MG TD at the San Francisco Golden Gate Race

Le Mans ’66 – The film

Brilliantly acted and beautifully shot Le Mans ’66 is a must-see for any fan of motorsport, and classic cars. Every scene is packed with some of the most stunning cars you’ll see on the big screen, with some nice mentions of our marque of choice! Matt Damon is brilliant as Carroll Shelby and you cannot help but cheer for Christian Bale’s Ken Miles. This is a film that deserves to be experienced on the big screen.

Shelby the record breaker

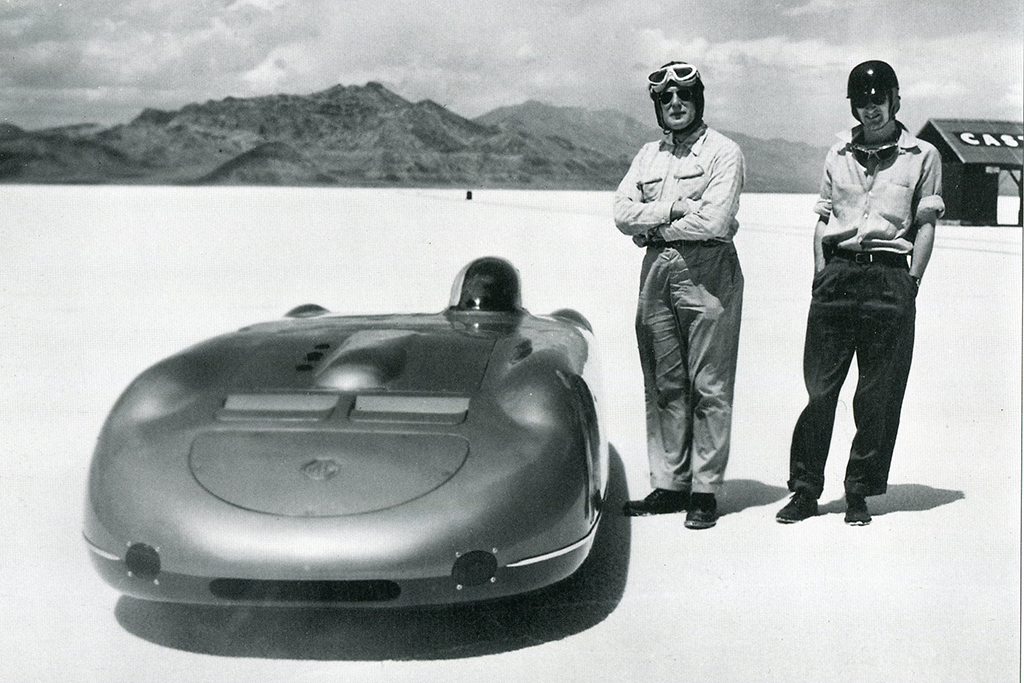

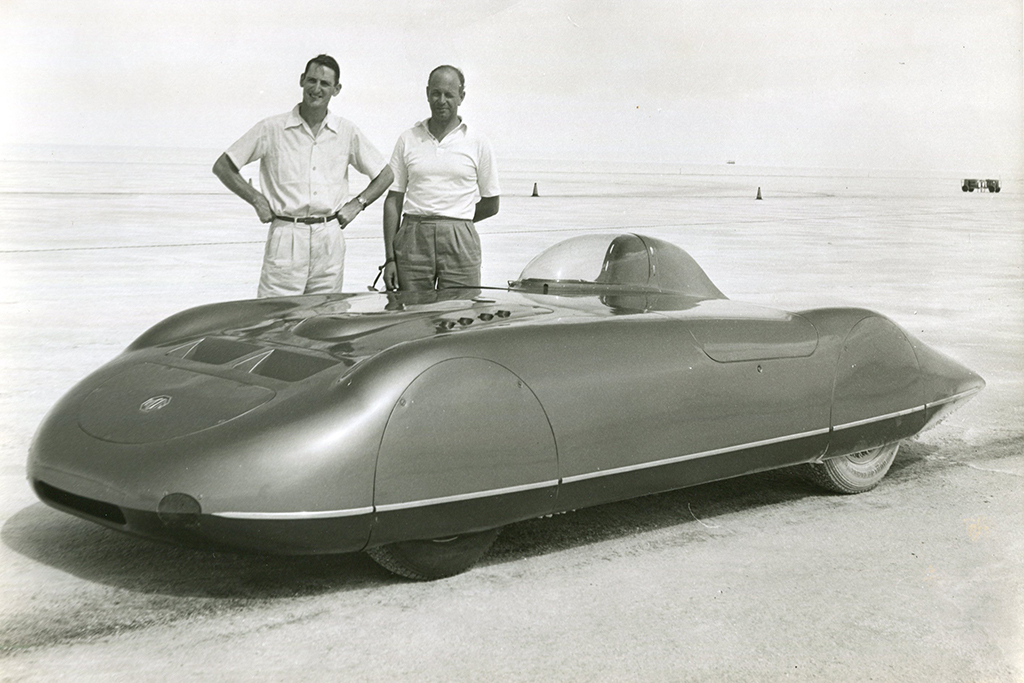

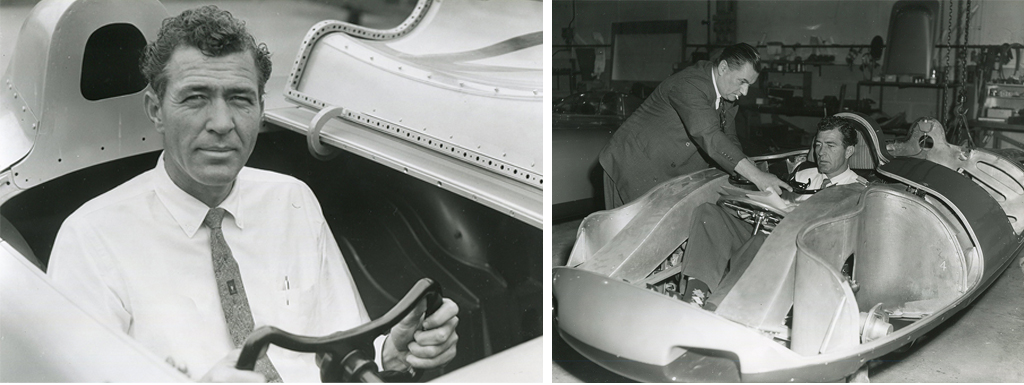

Every MG enthusiast knows the story of Stirling Moss and EX181, but what is less well known is that had things turned out differently, we might well have seen Carroll Shelby setting those records. In 1959 Shelby visited Abingdon to test a Spridget-based record breaker. Despite the best efforts of those involved, the Spridget project was shelved, and in the end EX179 would return to Utah in 1959. The pictures above show Carroll Shelby sitting in the shelved EX219 car at the MG Factory in Abingdon (left) and sitting in the cockpit of EX181 with Alec Hounslow looking on (right).

MG Car Club

MG Car Club