Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

Le Mans ’65

Peter Browning recalls the MG entry in the 24 Hours in 1965 when he managed the lone works MGB entry.

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

MG made a return to post-war motor racing in 1963 with a single car MGB entry at Le Mans. This was a semi-private but works-supported effort, challenging the ban on works racing participation by the BMC management at Longbridge following the 1955 Le Mans tragedy.

After a successful sortie (12th overall and second in the 2-litre class) the team retuned the following year with an official works entry and, with another MGB entry, again returned with a creditable result (19th overall and the ‘Motor’ Trophy for the highest-placed British entry).

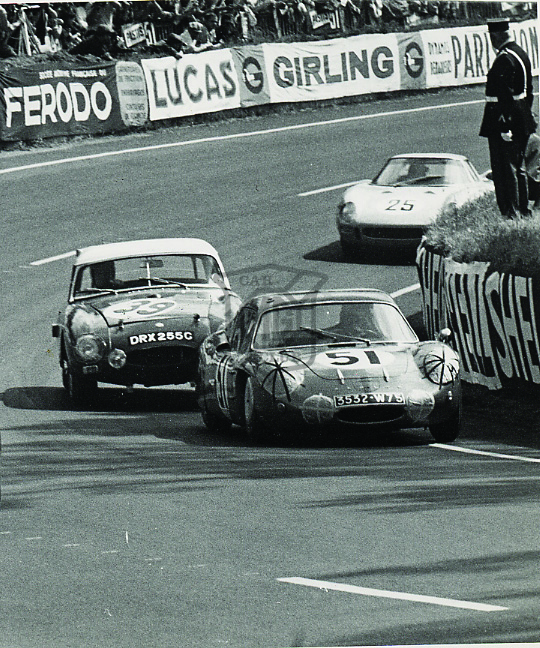

Aiming for a hat trick of finishes with a lone entry, we returned in 1965 for what was to be Abingdon’s final visit to Le Sarthe. Le Mans has always attracted worldwide motorsport interest and by the mid-1960s, while the main interest was on the new generation of sports prototypes going for outright victory, and in particular the much-heralded contest between the seven-litre Ford GT40s and the Ferraris, there was still keen support for the fortunes of the regular British ‘production’ sports car entries – MG, Sunbeam, Triumph, Austin-Healey and Lotus.

The performance differential between the new era of sports prototypes and the less sophisticated production cars, however, was starting to be significant. Minimum qualifying criteria set against the fastest car in each class had been introduced and certainly the speed differential was perhaps becoming dangerous.

It was certainly the new qualifying regulations which caused us the only real challenge of the weekend, because the MGB was as always in the same highly competitive two-litre class with the more highly modified Porsches.

The qualifying time around the circuit (with no Mulsanne chicane in those days) was just under five minutes representing a 100mph lap.

Despite running Stage five tune and with some weight reduction, the MGB needed a lot more top speed and this was achieved by fitting the now-famous droop-snout nose designed by Syd Enever from Abingdon’s Development Department. This produced exactly the right result, giving the car a top speed of 126mph and a comfortable ‘cruising’ lap time close on the 100mph mark. It was interesting that Syd‘s pre-race calculations and predicted top speed worked out exactly right!

Just to make sure, in qualifying we did have words with one or two of the British drivers in the front running prototypes to try and give us a tow down the Mulsanne straight if the occasion arose. This certainly produced some ‘cheaty’ quick laps but the drivers did have to be careful to pull out of the slip stream well before the sharp Mulsanne corner itself because the MGB brakes were not quite up to GT40 performance! On the subject of the droop-snout nose, used on all three Le Mans cars (1963-1965) there is some doubt today as to whether the same nose section was used on all three cars or whether one or more were built. Certainly we know that one nose was written off on the ex-1964 Le Mans car which was driven by John Sprinzel and Andy Hedges on the Tour de France.

More than one reputed ex-Le Mans MGB has appeared in recent times claiming to have the original droop-snout nose which is confusing. The final (1965) car, DRX 255C, certainly had its nose removed when it was sold and the car runs with standard bodywork. This is just one of the many unresolved mysteries of what actually happened within the Competitions Department at the time when memories today of those involved (including myself) have faded on things which at the time did not seem to be that important! Compared to today, the MG equipe to the 24 Hours 36 years ago was a very small and unglamorous outfit. The race car was towed to the circuit on an open trailer, two or three works mechanics came from Abingdon, while our pit equipment, tools and spares were pretty modest.

The average Club MGB racer today probably goes to the circuit better equipped! There was no lavish team catering or hospitality, friends bought along a small caravan to provide simple food and drink. The all-important Mulsanne signalling team was run by a regular group of MG enthusiasts, dedicated volunteers who camped out each year and whose only contact with the outside world was the French ex-army field telephone land line to the pits, which provided a totally unreliable means of communication (no mobile radios in those days!).

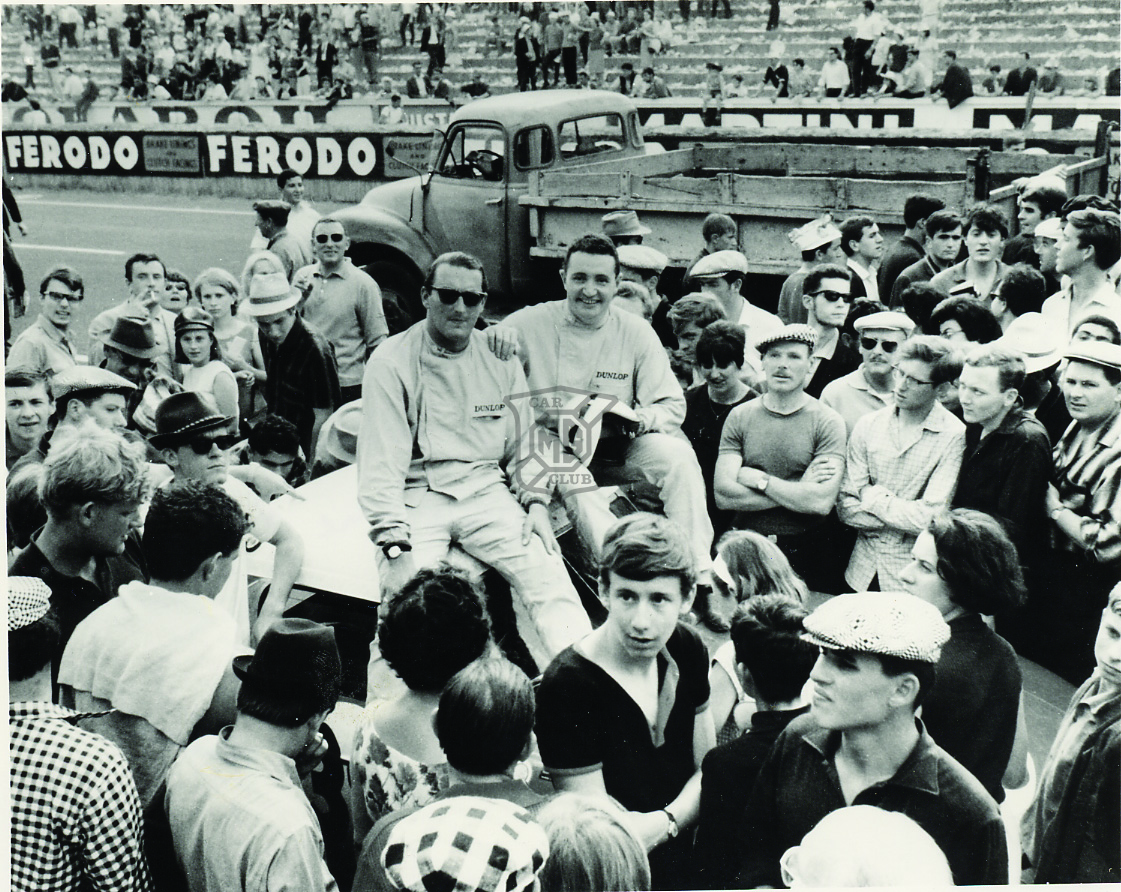

After satisfactory qualifying by both drivers – Paddy Hopkirk and Andrew Hedges – our race plan was established and was very simple. We divided the 24 hours into 10 sessions of two hours and about 20 minutes this being dictated mainly by the fuel consumption. With a 20-gallon tank and fuel consumption of around 14mpg, we had a range of around 280 miles and planned on maintaining a 100mph race average.

As with all of our racing activities with the works MGBs, we were only there really to put on a display of reliability. Our chance of success was to be there at the finish to hopefully pick up a promotional class placing plus the best overall position that we could achieve when the others fell by the wayside.

The only time when we actually went ‘racing’ was if one of the other British teams got too far ahead and then we would put on a bit of a spurt to keep them in our sights. This meant that we would be in striking distance if towards the finish we could ‘attack’ if they were still running. Compared to today’s race strategies it was all very simple, and with the almost total reliability of the MGB we very seldom veered far away from outset race plan. Certainly in 1965 the car ran like a train and we finished 11th overall and were runner-up to a Porsche in the two-litre class, which actually pulled into the pits on the last lap with a blown engine! The MGB just failed to win the ‘Motor’ Trophy again being beaten by the whispering Rover-BRM gas turbine which finished in 10th place.

The hat trick of Le Mans finishes with a lone entry achieved exactly what John Thornley told us to do – demonstrate MG reliability using a car that basically used off-the-shelf competition tuning parts available to any owner.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club