Journey of a lifetime

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

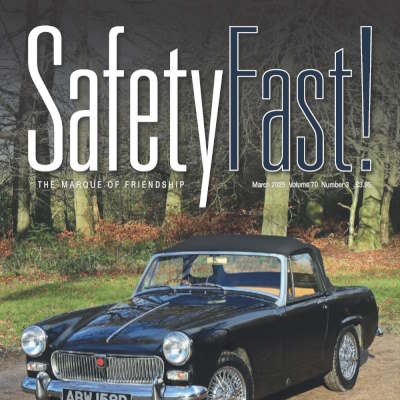

This month’s feature from March’s edition of Safety Fast! follows the story of a man and his MG Midget on an incredible journey of a lifetime. Words and photos by Clive Stokes.

‘Midgers’ ready for the off in 1964

‘Midgers’ ready for the off in 1964

First registered in December 1963, I bought my MK1 Midget, known as Midgers, with less than 2,000 miles on the clock, 10 months old, for the then-princely sum of £500. The equivalent in today’s money would be around £9,500. This lovely little car was pristine, Old English white with red interior, resting in a breaker’s yard (reason unknown) pleading for a good home.

After paying a small deposit, there and then, I only discovered later that there was a significant sum outstanding on Hire Purchase, as it was then known. I would not return to collect until I had written confirmation that this had been cleared; again, we didn’t have the luxury of websites to assist.

The rack and pinion steering was so much more positive than the sloppy steering on my 1948 Ford Prefect. I found that I was all over the road with constant over-correction, that I had to stop. You see, my escort was driving a Daimler Dart and had to slow down as I was too dangerous at his speed. My lifelong love affair with MGs was about to start, but I was totally unaware of that at the time.

The year 1964 was a time when the asphalt in front of you could stretch for miles, and when driving possessed a certain sense of adventure. Garages – not filling stations – were much more prevalent and one had to either carry a spare gallon or be aware of when next, a fill-up would be required. In these garages, too, were men who knew mechanics, actually had welding equipment, skill and imagination, who could fix things. It was not at all like the modern, impersonal ‘drive through petrol stations’ of today.

With the hood down and the wind in my hair, I started to explore the highways and byways of the wonderful English countryside, feeling a mixture of Toady in Toad of Toad Hall, Jack the Lad and/or the dogs “doodahs”. And then I met this beautiful 19-year-old Swedish girl which changed everything. Suddenly the madness of being in love hit me like an express train.

This was the summer of 1965 when I was a young blade of 26 years. It was the magical sixties when youth rebelled, Rock and Roll boomed, The Beatles arrived and the mini-skirt was not far away. There was a sort of magnetism in the air, with women burning their bras, rebellion from the underclass as if they had walked through a restricting mist and were now asserting themselves. This was post-war Britain in all its raw assertiveness. Unbelievably exciting times, with new inventions, new ideas, new horizons, and most importantly, new ambitions with new possibilities. The yoke of war had finally been broken and youth were going berserk with their new-found freedom and an ever-improving disposable income.

I found myself leaving the northerly sea-port of Immingham, in Hull, on my way to Gothenburg on the dodgy old wooden tub of a Swedish ferry called the Suecia, with absolutely no stabilisers. The North Sea can be brutal and this tub of a ship rolled and pitched like a brewer’s barrel being tossed into its cellar. I learned later, after a very rough crossing, that it was being withdrawn from service as newer ships were replacing it.

My trusty little Midget was full of Osa’s luggage together with mine, but this little motorcar was like a young spaniel excited at the prospect of an outing and could not wait to get going.

Osa – the cause of this incredible journey

Osa – the cause of this incredible journey

When we docked this very large young Swede came up to me and asked me if I was going to Stockholm, to which I answered yes. “I see you are alone. Could you possibly give me a lift? I am broke and need to get home.” I told him that I had a very small car that was already crammed with luggage and then I suddenly thought there could be a beneficial possibility here. “If I can shoehorn you into the car and get you there, would you be able to put me up?”

We struck a strange deal. “We will have to drive with the hood down and your luggage on your lap,” I said, as we got to the car. Eirik was 6’ 6” and had been rather a naughty boy playing away from home and told me that he would have to ask his wife first. But remember, this was Sweden and ‘free love’, and it was the sixties. It all depended on her immediate reaction when he opened the front door. Strange, these Swedes, but incredibly open and honest with a warm generosity, practical, they saw life as it was and not as some romantic dream.

I aimed the bonnet towards Stockholm, pressed the accelerator and shouted “Tally Ho”. Eirik gave me a look and probably thought, strange, these British.

I parked the little Midget outside Eirik’s flat whilst he went inside to negotiate my future lodgings, since I, too, wanted to reside in Stockholm. After a nervous 10 minutes or so, the door opened and I was beckoned forth.

Lovely flat, lovely people and, boy, did I have the luck of the Irish. I was only three blocks away from where my girlfriend lived in a high-rise flat and pondered the chances of this happening in such a city as Stockholm.

Osa and I met up with an English pal of mine, who was living in Sweden with his Swedish girlfriend and spent the weekend at her parents’ summer house. I remember travelling with the hood down and two other adults sitting on the rear bulkhead with their legs down behind the seats, our luggage on the rack. Authorities were extremely hot on ‘drink driving’, even then, but somehow ignored what would be considered dangerous today. Strange, that.

We took Midgers into Norway and stopped for petrol at a filling station somewhere north of Bodor. A certain Eirik Furebottom – pronounced firboten – came to fill us up. As soon as he realised I was English he said: “You comm…” So I comm.. If we were not in the Arctic Circle then, we drove well into it later on.

Osa and I followed him into his house where we met the family who were watching Manchester United on the television! Clearly, they were great fans. Eirik went and got out his ‘private collection’ of beer and said: “You drink”. I drank. His storage was outside in a cold cabinet. Poor Midgers was forgotten about for the next 16 hours or so, as we were guests of the family. Out came the Bremvin – a kind of schnapps. Osa warned me that if I started drinking she would go to bed. Eirik and I went midnight fishing in the mountains for uret – a sort of mountain salmon. All I achieved was getting my tackle caught in the nearby trees! We returned and ate a very well-cooked meal, as it had been left on the top of the stove for some hours.

I said to Eirik: “Short of giving me your wife, you could not be more generous – why?” This all in broken English. He replied: “You comm.” So again, I comm…

Outside in his back yard were mossy banks and big fir trees, with stepped banking going away from his property. He said: “You, my friend, you fought hand to hand against the Germans”, with great emotion, shaking my hand.

Bodo had been captured, as it was a vital steel-producing town, and poor young Eirik’s town had been occupied and I guess the relief of the British Army relieving them was imprinted on his memory. He could not do enough for us.

We drove off the next morning the greatest of friends and some distance down the road I said to Osa: “We didn’t pay for the petrol!” I went back and paid him and for my trouble, he gave me what must have been his most treasured possession: a cured shoulder of reindeer meat. That meat travelled to hot Spain, and when I got back to England it was still edible, which says something for the skills of the Eskimo.

We hit rain on our way south and the little white car became almost a grey-black with all the mud spray from the dirt roads. I could only just see out where the wipers had swept, it was that bad.

I can’t remember much about the journey from Norway down to the south of France, but I do remember that we had a mother of a row over something. Prior to this, I had given all my money and passport to Osa for safe keeping. She said something about it being safer, which I challenged. Anyway, immediately after the row I got back into the car and we shot off. She had left her handbag on the pavement with all our money, and passports, too.

From an idyllic trip so far, our nightmare suddenly began. It was the year that Harold Wilson had devalued the pound and actually said on television that the money in your pocket would not be affected. There was a universal limit of £50 per person for foreign travel spending money (£900 in today’s value) – the country was broke.

We managed to get the French police to stop British motorists to allow us to beg from them what little money they could afford and managed to scrape up around £30 or so. At the police station, we learned that a road block had been put in place and that the police were confident they would catch the thieves since there would be three different currencies in their possession, Swedish, English and French.

We waited several hours as a variety of calls came in with the devastating message: “Absolument rien”. It was then that we realised that we had lost the lot. With no passports and very little money, we were in deep, deep trouble.

It was a Friday and it meant that we would have to blag our way into hotels without passports. It also meant that I had to drive half the length of France from the deep south to Paris and back in four days, a matter of nearly nine hundred miles, but the little Midget was up for it. We had to report to the Swedish and British Embassies in the hope that we could obtain ‘emergency passports’.

Once in Paris, I sent a telegram to my Father: “Been robbed send money”. He was used to his second son getting into all manner of trouble, so I hoped that the poor man would not be too shocked.

How we managed to gain access to hotel bedrooms without passports I cannot fully recall, but we did it somehow. I remember that we sat down on some steps in Paris and shared a hamburger and bottle of water between us. We were broke and the money had not yet come through by then, although I was offered a bed for the night by a very accommodating (no pun) young French lady in the Westminster Bank, as I had explained my problem to her when enquiring if my money had come through.

The British Consul instructed me to obtain a mug shot to enable them to issue me with an Emergency Passport. The Swedish Lady Consul was more interested in attending an embassy ball and simply said: “She will have to be sent home”. “Impossible,” I replied, “her parents are away, her house key is in my parents’ home in England with the rest of her clothes.” Finally, the rather trumped-up Madame conceded that it would be best if Osa stayed with me, so a second Emergency Passport was required.

We were advised to visit a photographer on the Champs-Elysées but when he quoted his price, out of a continual build-up of frustration, I very nearly wrecked the place. I managed to get what were then called ‘photomatoms” from a photo booth. Was I ever proud of my Father, stepping up to the plate like he did, since money finally came through to the Westminster Bank in Paris.

The British Consul showed me just how these sorts of photos could be forged, but under the circumstances issued me with my emergency documents, as did the Swedish Embassy. We were once again legal citizens and were on our way south again.

It is strange how shocking situations affect people since, when I was sorting out the contents of the boot, I came across this envelope with perhaps around £30 in. It had been my ‘emergency fund’, which I had completely forgotten about. Was I surprised when I found the cash, which I waved to my girlfriend saying: “Tonight we will have a really special meal to celebrate our survival against life’s tribulations”, and we did. I was in the money – big time, since I also had the money that my father had sent me.

It could have been in St. Tropez for all I remember, but I had ‘fruits de la mer’ but the blessed shellfish were still alive. The waiter had taken an instant dislike to me and thought he would teach this British Roast Beef a lesson – why I know not.

If I had eaten any of them I guess I could have been really ill, but I sent them back. Perhaps he thought that I was a truly spoilt English brat, with money and a delicious blonde girl on my arm – who knows? But I did think “why does it seem always to happen to me?”

The reindeer meat survived extreme temperatures and was still quite edible, even when I got back to England. I thought of Eirik Furebottom and his family, his wartime experiences and how strange and diverse life could be.

My trusty MG Midget did not miss a beat. I discovered later that it had a ‘development engine’ in it, since it had double valve springs, parts that were not listed in the ‘workshop manual’. I telephoned the main dealer in Hammersmith where I was told “you don’t have those parts, Sir”. “That’s strange since I have them in my hand!” I replied.

The first thing I did when I got home was to go and thank my Father profusely, for his kind and prompt generosity.

“That’s all right, Son,” he replied, “It was your money, taken from your account.”

MG Car Club

MG Car Club