Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

The Early Days of the MG Midget

By Mike Allison

This article is based on a transcription of notes made in longhand by me after talking to the various people mentioned herein during the 1960s and early ‘70s. I changed the English a little, and ignored the swear words, often used for emphasis. Many of the stories were repeated several times and I have no doubt that they are historically accurate; remember, it was still barely 30 years after the events described, and the old MG employees were proud of their achievements, which spoke for themselves, and when I heard the stories, it was still like “yesterday” for them.

There can be little doubt that just as small ships had launched a great empire, so the smallest of cars launched the MG marque and brought sports cars to those with relatively small incomes. In the period following the Great War, there was a plethora of small companies which brought motoring into the realms of the middle class, and many of these built worthy transports, but it was Morris Motors who really brought personal transport to those of modest means. Morris made this possible simply by cutting prices to a level that others could not achieve, but while doing so made sure that his cars were amongst the most reliable of their time. The nascent MG Car Co started building specially bodied versions of the reliable Morris Oxford, and then sought to increase their market by producing four-seat sports cars with larger engines. In 1928 Morris Motors started work on their small car to rival the successful Austin Seven, versions of which were being raced at Brooklands. The new Morris was based on an unborn Wolseley car, which company William Morris had personally bought out of receivership in 1927. It was a logical step for the MG Company to exploit this small car, and the results were quite extraordinary.

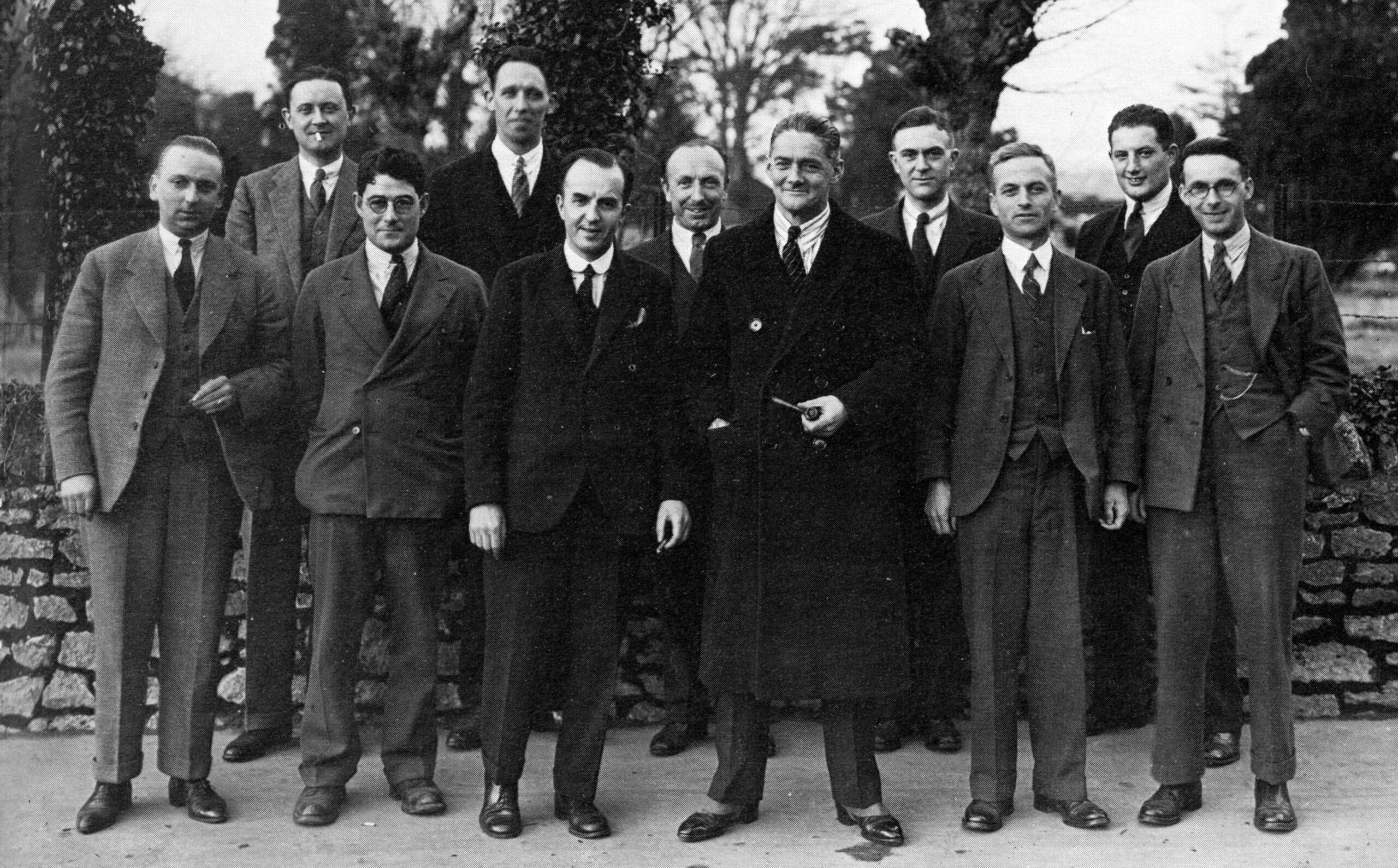

During my time at MG (1964-1973) I had the privilege of working with many of the people who had been around when the Midget was in its early days, some of them from the start of the MG car production.

Cecil Cousins (Works Manager until 1969) had been apprenticed in the Morris Garages workshop and became a fully-fledged mechanic in around 1919 and rose to be shop foreman at Longwall Street by the time Cecil Kimber came, so his claim to be one of the “originals” was well justified. Frank Lowndes had recently retired, but called in every week, so I met him. Frank Stevens was similar, and his son, Dick, was a line foreman in my day, whom I knew well. Harry Herring was also just about to retire, but his son, Jack, carried as the official coach-builder and model maker until the end in 1980. These men were all at Longwall Street and followed the Factory through all changes until age caught up!

Reginald Jackson was recruited by Cousins in mid-1928 as development engineer and was joined by Hubert Charles when he moved from Cowley to Abingdon as Chief Draftsman, in charge of all development, although Charles had worked “unofficially” for Kimber since around 1926, from the Cowley Drawing Office. Gordon Phillips had started at Edmund Road in 1927, and assisted Jackson. Fred Kindell joined the group at Abingdon, when the new factory started work, to work with Jackson, while Frank Tayler was also an assistant through a large part of the story. Sydney Enever worked at Cowley initially as a tea-boy, which entailed working with the mechanics and learning his trade, and transferred officially to Abingdon during 1931, although he had worked spells with Jackson when the workload demanded more than four hands!

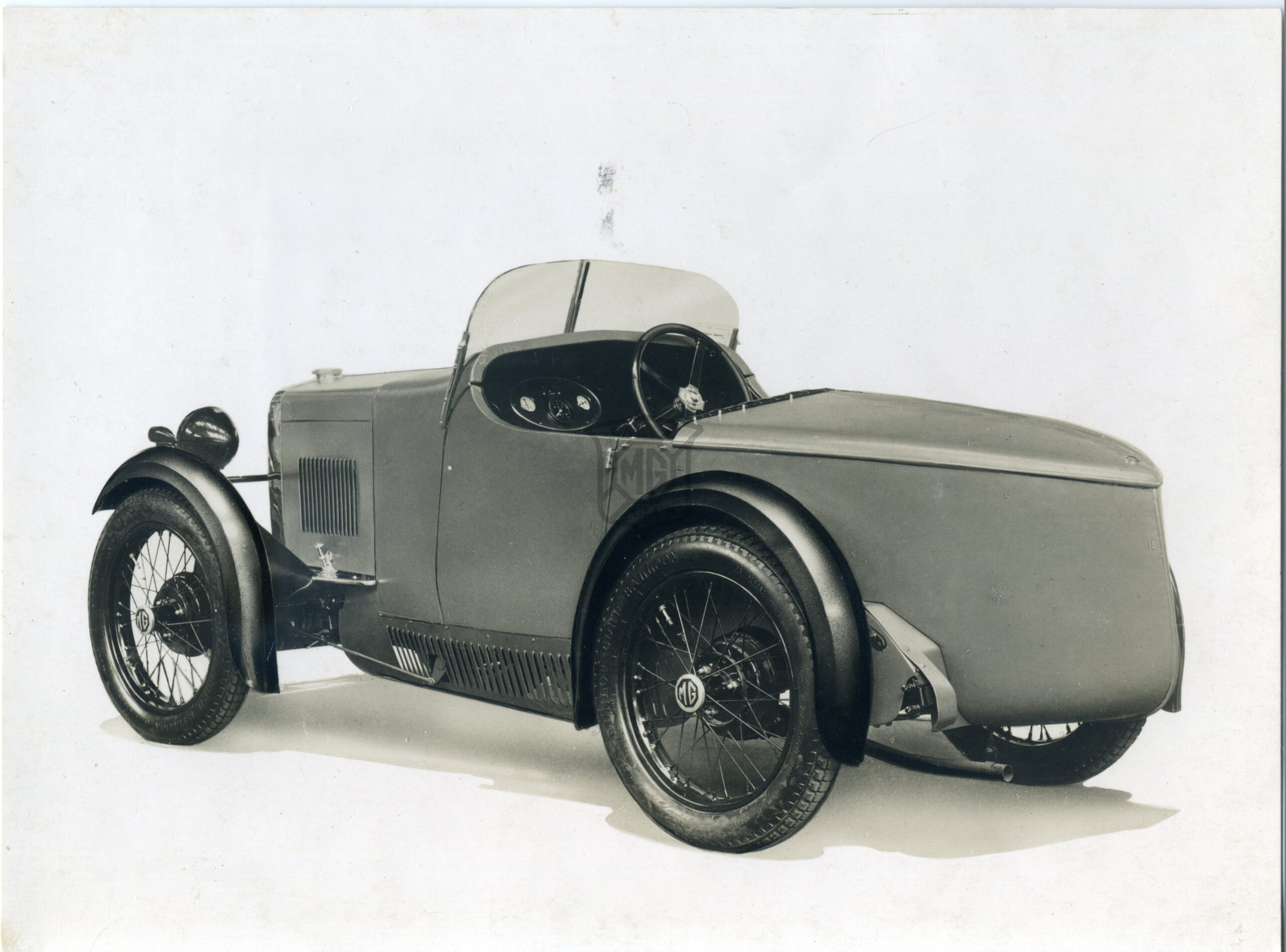

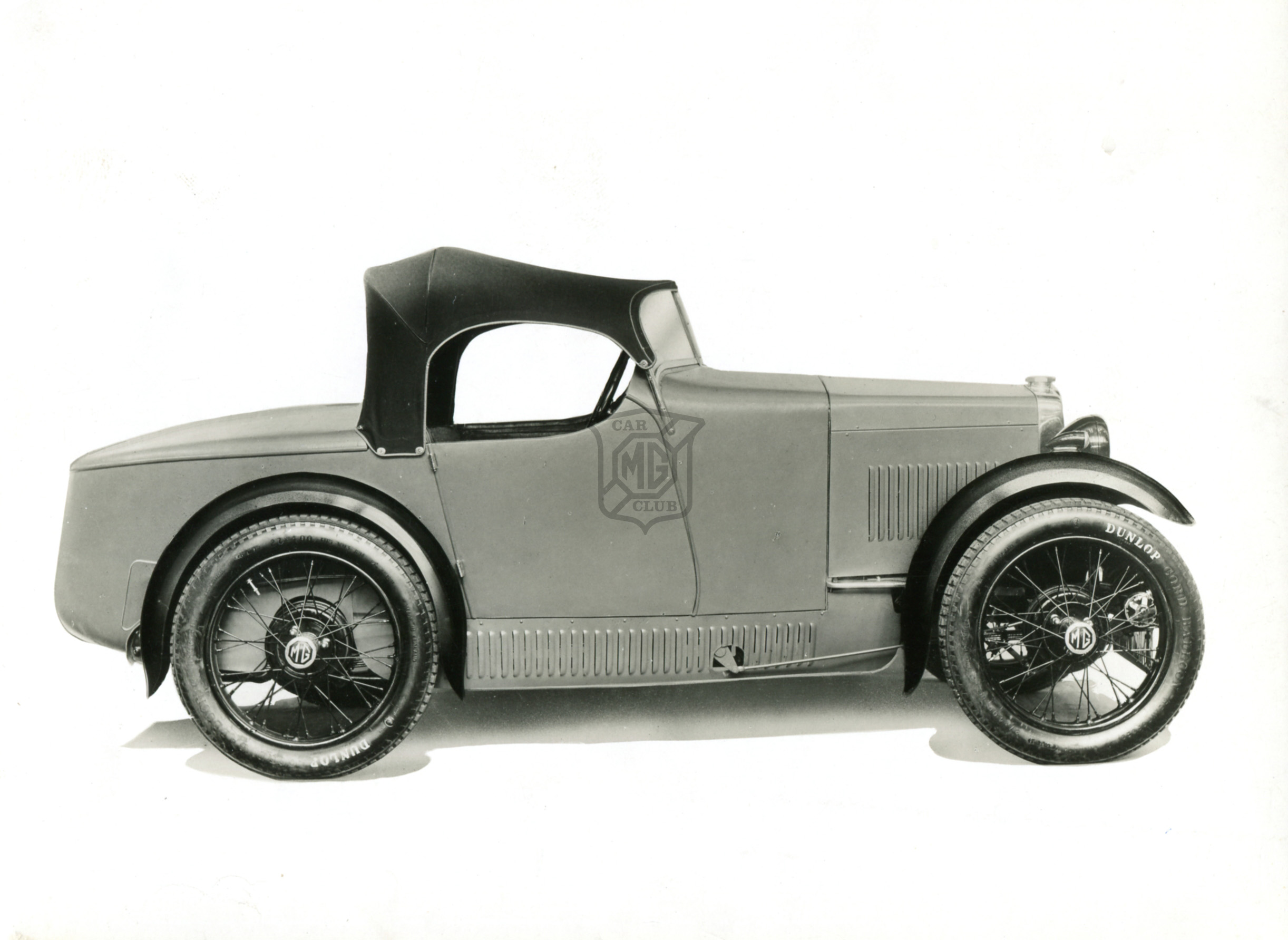

Jackson was initially responsible for making special parts, and making sketches of these, for the new MG “Six” (later called the 18/80) which was taking shape in 1928, and then getting his sketches translated to “proper” drawings at the Morris Motors Drawing Office, probably by Charles. It was during one of these visits that he saw a Morris Minor prototype, and quickly saw the potential for a small MG based on this, and talked over his thoughts with Cousins, who passed the ideas to Kimber, whose message was “Concentrate on the Six”. However, Jacko had already spoken to Charles, and he relayed similar thoughts to Kimber, who then agreed to Jackson having a chassis to investigate the idea. The job was officially known as “EX101”, but it took but a few days for Jackson, Cousins and Phillips to lower the steering column, and fit a wooden boat-tailed body, “inspired by the Type 35 Bugatti, but bearing little resemblance to it” Cousins told me! Kimber sent the body off to Carbodies Ltd, and within a week the first two bodies arrived at Edmund Road to be fitted to chassis. Kimber liked it, and got a second chassis over, for the car to be present at the London Motor Show in September.

There was no second engine, so Harry Herring made a wooden replica engine for the Motor Show stand, and the bonnet was kept firmly shut, while the other car was accorded the chassis number EX101/1, was registered (WL 6523) and was used a demonstrator at the Show. Over 200 orders at £185 were taken for this car, while the Six only had a few firm orders at around £500 taken. This immediately set a major problem, as Cowley had also had considerable interest in the Minor, and so far, only a dozen cars had been built. Production of the engine was started, at Wolseley, who also supplied most of the running gear, and it was the following spring before the orders could be followed up. Even though the 14hp MG models were winding down, it was immediately apparent that Edmund Road was too small to accommodate the building of around 500 cars in eight months, and so a new works was sought.

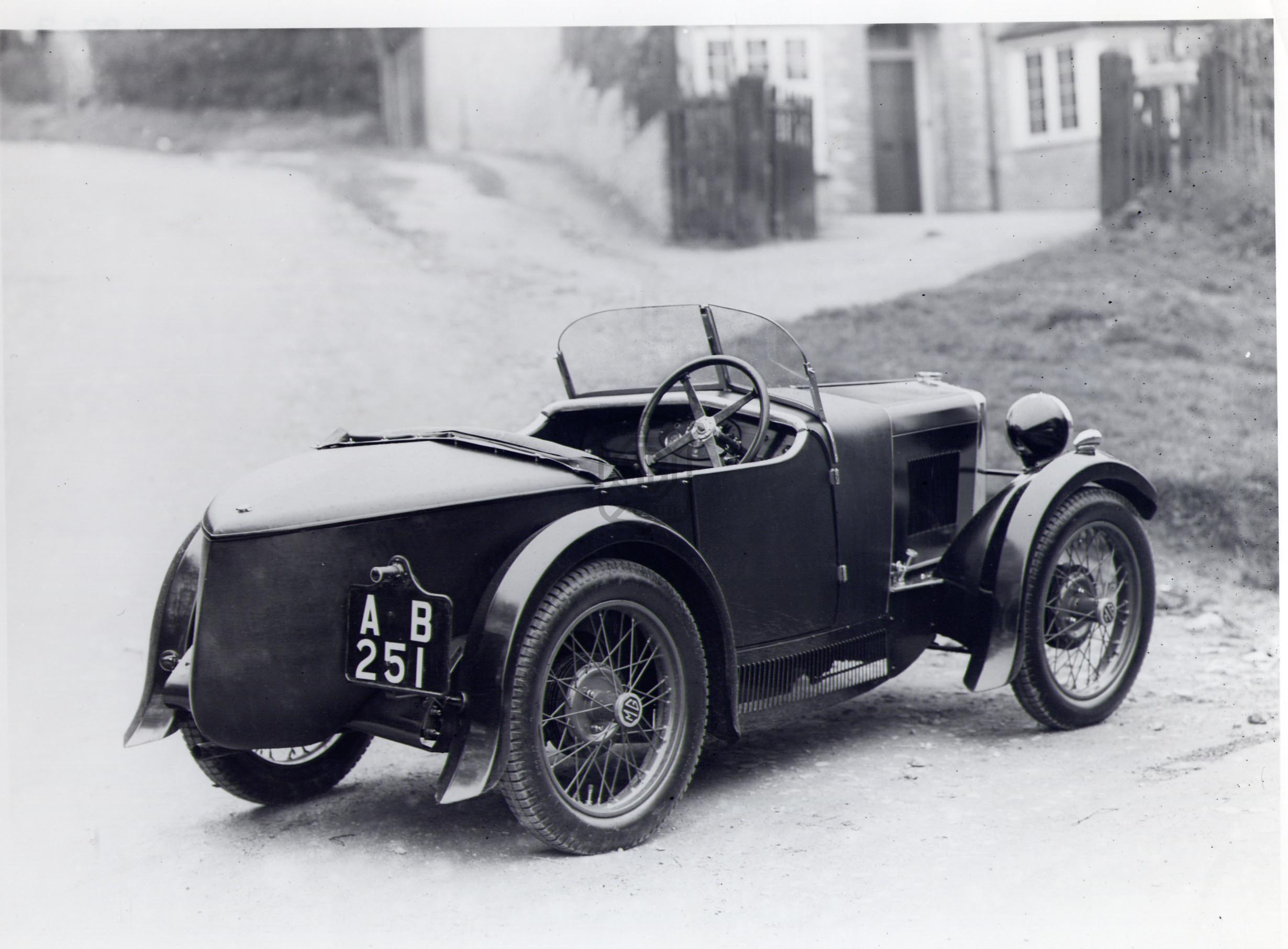

Production of the model started in April 1929, with minor modifications, at chassis number 2M/ 251, the upswept scuttle of the prototype cars was done away with, to get the price lower, and the prime cost of each body fully trimmed was £5.10.0 (£5.50 in today’s money) or roughly twice each worker’s weekly wage in the factory. Production was crammed into the small Edmund Road facility, and 500 were built by the end of November, although finished cars were moved to various places around Oxford before shipping. Orders were still coming in at a high rate and this again raised the problem of factory space, and the now-redundant trench-coat and saddle factory of the Pavlova Leather Company Ltd at Abingdon became available and the freehold was bought by Sir William Morris, for around £50,000, with an agreement to leave the artesian well available to Pavlova indefinitely. A further equal sum was put aside to move all equipment and refurbish the place.

The first Midget cars to be built at Abingdon started in February 1930 at Chassis 2/M 751. Chassis numbering at the time was like that, the first number or letter indicating the body style, the letter the series (M for Midget) and the next digits the serial number, starting with 251. This, at Abingdon, was stamped on the frame in groups of ten, but the withdrawal of these was haphazard, and not necessarily sequential. The 18/80 model was just a four-figured number starting at 6521. The 14/40 Mark IV had started at 2251 (the phone number of the Edmund Road factory); prior to that the 14 HP cars had just had the Morris chassis number and carried a Morris Motors guarantee. When the Mark II 18/80 was introduced, this became the “A-type” MG, with numbers starting at A 0251. The Abingdon phone number was 0251, by agreement with the Abingdon exchange, these, of course, being the days before STD, when all long-distance calls were operator connected.

The Midget chassis frames were made at Abingdon after 1930, once the move was completed, with forged parts made by Wolseley, and by the James Motor Cycle Co., which had good foundry facilities. The axles and chassis side members were supplied by Wolseley, as were the engines and gearboxes. Steering boxes came from Adamant Engineering of Luton, electrical components by the Rotax Company of London. Most other parts were either made at Abingdon or sourced locally.

During 1929 a team of three Midgets had been taken to Brooklands by Cousins, Jackson and Frank Tayler to be driven by the Earl of March, Harold D. Parker and Leslie G. Callingham to run in the one-hour High Speed Trial at the JCC Member’s Day meeting in April. It is thought that each had bought a car, and while they hoped to achieve 60 miles in the hour, they were not far adrift of their target, which surprised all! These cars have not been identified, but were registered WL 7171, WL 7180 and WL 7182, in a photograph reprinted in John Thornley’s book “Maintaining the Breed”.

Following this, and about the time Charles officially joined the MG Company, Kimber allowed Jackson to use one of the press demonstrator cars to see what he could do about improving engine outputs. Jackson told me it was a blue car, which had been beaten up on several trials, and he believed “Buckingham had used it a lot”. This would identify the car as 2/M 256, registered WL 6557. Checking the valve timing he found there was no overlap of valve opening at TDC, so he got an unground forging from Wolesley and hand shaped it to get a little, and then had it hardened at the Wolseley Works. The result was amazing, the engine being livelier straight away. He then obtained better results by adjusting the timing for each cylinder to be the same. From his motorcycle experience, Jacko realised that it would be better if a larger inlet valve was used, and he introduced one a sixteenth of an inch larger, polished the ports, matched manifolds with ports, and so forth. He then took the “bottom half” apart and polished rods and crankshaft and lightened the flywheel by a few pounds. All this polishing work earned the car the soubriquet “Shinio”, even though the outside of the car was somewhat battle-scarred and even tatty! Jackson and Charles drove the car as a “shop car” until well into 1932, when it was broken up having served its use.

The camshaft was redesigned by Charles to give similar results, and was available in early 1930, manufactured at Wolseley, and fitted to all Midget engines after the 12/12 race. The larger inlet valves were only introduced for the 12/12 cars, though.

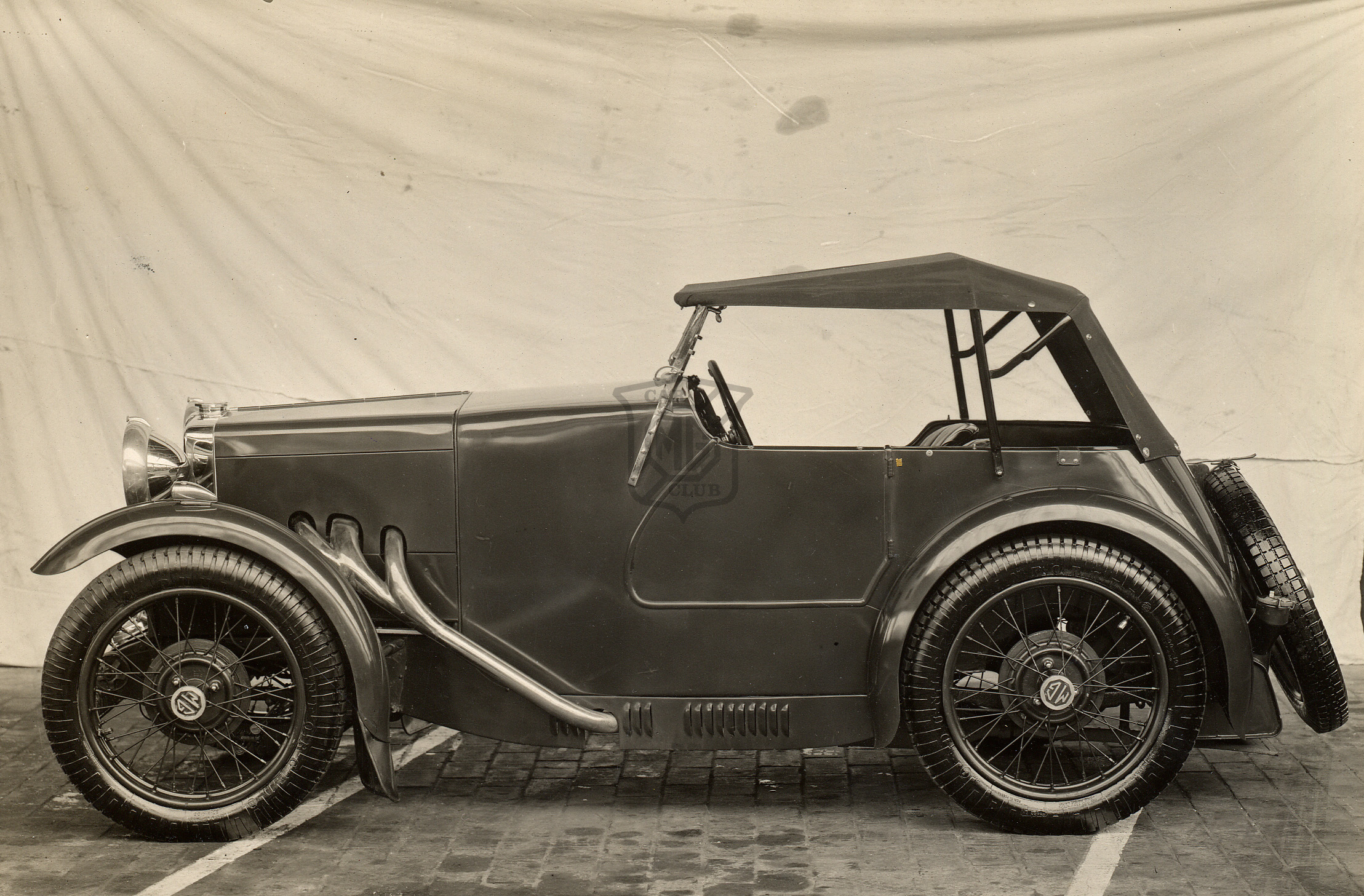

In order to create brand loyalty, a two-door saloon was created and dubbed the “Sportsman’s Coupé”, to appeal to the young family, but appealed more to the ladies, it seems, since the wind was kept out and did not upset the hairstyle, and one was dry inside should it rain!

To be a real sports car, the model needed to take part in sporting events. Trials and rallies were soon required to make classes for small, cheap cars, but exposure in racing events was more difficult, and simply “not allowed” by William Morris, unless such racing was done by owners of cars at their own expense.

Cecil Randall, a successful market gardener in Essex, had bought an open model, and while he had raced various cars as a hobby, he teamed with a neighbour, Bill Edmondson, who was just starting to dabble, and they decided to approach MG about entering a team of cars for the prestigious Double-12 Race to be held at Brooklands in May 1930. This was around the September of 1929, and just as plans were being laid for moving the production to a new factory in Abingdon. Three cars were laid down, fitted with the new camshafts and carefully put together, with exhausts complying with the Brooklands track regulation, and with slightly modified bodies. In the event two similar cars were ordered, one by Norman Black, the London car dealer, and by Miss Victoria Worsley who was making a name for herself as a competent racing driver in a Salmson car but was using her brother’s Midget on the road.

The Randall team took the Team Prize, and the other two cars ran reliably, all five averaging around the 60mph mark for the 24-hour run, which brought a lot of press attention, so much that a Double-Twelve Replica Midget was produced and 20 of these were sold. Sir Francis Samuelson wanted a car to use in the Le Mans 24 Hours race, and A. Murton Neale ordered a similar car. These were similar to the 12/12 cars, but the bodies had to be altered to comply with the Le Mans regulations. All these cars were fitted with a larger (1.25″ choke) downdraft carburettor mounted on a special manifold, the Le Mans cars using the standard underfloor exhaust system but having a special three-branch manifold welded up by Fred Kindell.

When Charles started to work exclusively for MG, he decided a better chassis was needed as much as more power, and started work under the code EX120 on this improved chassis. However, he had already simplified the braking system on the Midget, dispensing with the somewhat complicated rod and cable system, and providing, as he had for the 14/40 cars earlier, four cables operated from a centrally mounted cross-shaft. The new chassis however went far further, providing a low frame which swept over the front axle, but under the rear axle. Fairly stiff springs were used damped by Andre-Hartford shock absorbers. This chassis was deployed at the behest of George Eyston, who had a home in nearby Milton, and had been successful as an amateur racing driver in a variety of cars in collaboration with his brother, Basil. George wanted to have an attempt at being the first to drive a “Baby car”, i.e. one with an engine capacity of less than 750cc, at 100 mph. The Austin Company were spending large amounts of money with similar intent, so far unsuccessfully.

Eyston was being financed by Jimmy Palmes, of Surrey coachbuilder Jarvis, and by Ernest Eldridge, the former land speed record holder. Eyston had put money into the Jarvis company previously, who became MG dealers for Surrey and Palmes was able to get a couple of unmachined cylinder blocks from Wolseley Motors, presumably using Charles as an intermediary, and keeping the project “under the blanket”, thought Jackson.

It took until early 1931 to achieve the magic 100, but Austin were beaten to the target, and even Kimber had finally been convinced that the small engine cars were the way to go… the rest, as they say, is history.

The complete history of the growth of the MG marque into a sports car of world stature is covered in detail in the book “Works MG” by Mike Allison and Peter Browning, recently reprinted by Osprey and available from Kimber House.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club