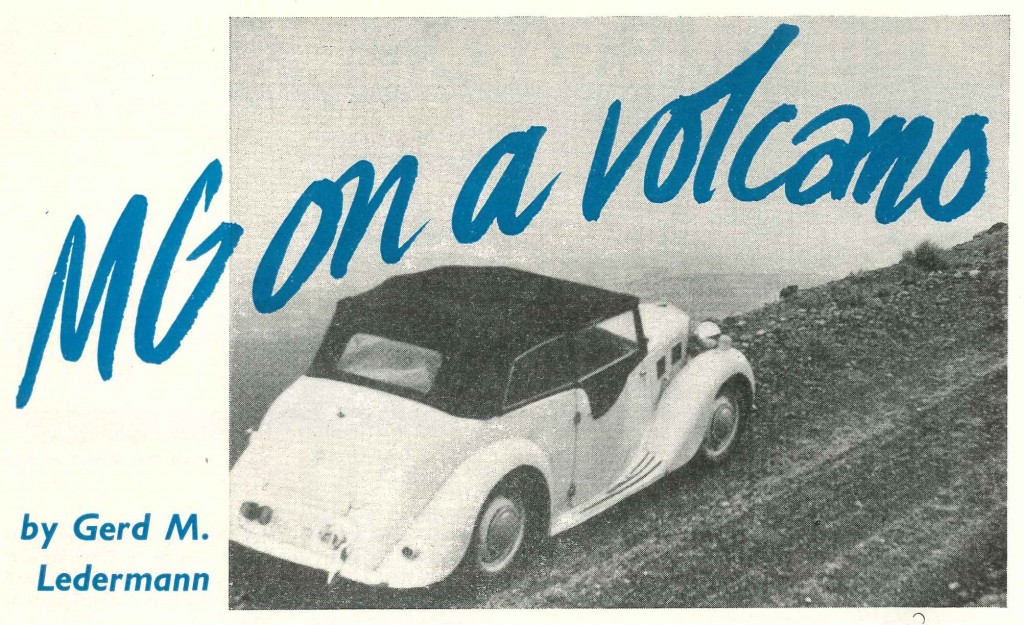

MG on a volcano

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

A holiday trip by three Canadians up a Mexican volcano with a Y-type M.G. turned out to be more of an adventure than they expected. MG on a volcano featured in Safety Fast! from January 1963, and was written by Gerd Ledermann.

In the summer of last year, my slightly antiquated but decidedly youthful-looking M.G. ‘Y’ type tourer (of ’49 vintage) brought me safely and without much effort from Montreal to Mexico City.

More than holding its own, it flitted through the erratic traffic of that fascinating metropolis, obviously feeling pleased with its performance and the invigorating atmosphere. It couldn’t suspect what was in store for it within the next few days. Just beyond Mexico City’s surrounding mountain range lies the famous market town of Toluca.

Every Friday it is a colourfully crowded place, when the inhabitants of the nearby district pour in to sell, bargain, buy, or just to have a good time. However, on this particular afternoon Peter, John and I did not stop to stroll about at leisure in the warm sunshine, as we had done on former visits. We were in our way to reach the top of Nevada de Toluca. This extinct volcano, its twin peaks often shrouded in clouds but easily discernible on a clear day, provided a natural challenge.

The map indicated a secondary gravel road to the base of the mountain, marked as a National Park, and we could foresee no undue difficulties. But these soon became apparent. The choice of tracks and donkey trails was abundant and confusing. We drove into several villages, hood down, with a puzzled look on our faces and unmistakably in need of directions.

These were usually provided in detail, but varied according to the imagination, descriptive skill and enthusiasm of every helpful bystander: `See that church steeple straight ahead? Well, turn right just beyond it, then left after one block and straight up the hill,’ or, ‘Just follow those two donkeys across the plaza and up that little street.

They’ll stop at a corner; turn right there and keep straight on, out of the village.’ Yet we always ended up by turning back, when neither reverse gear nor a few pushing Indians were of any avail to overcome the steep inclines blocking our attempt to approach the mountain. It retained its lofty distance.

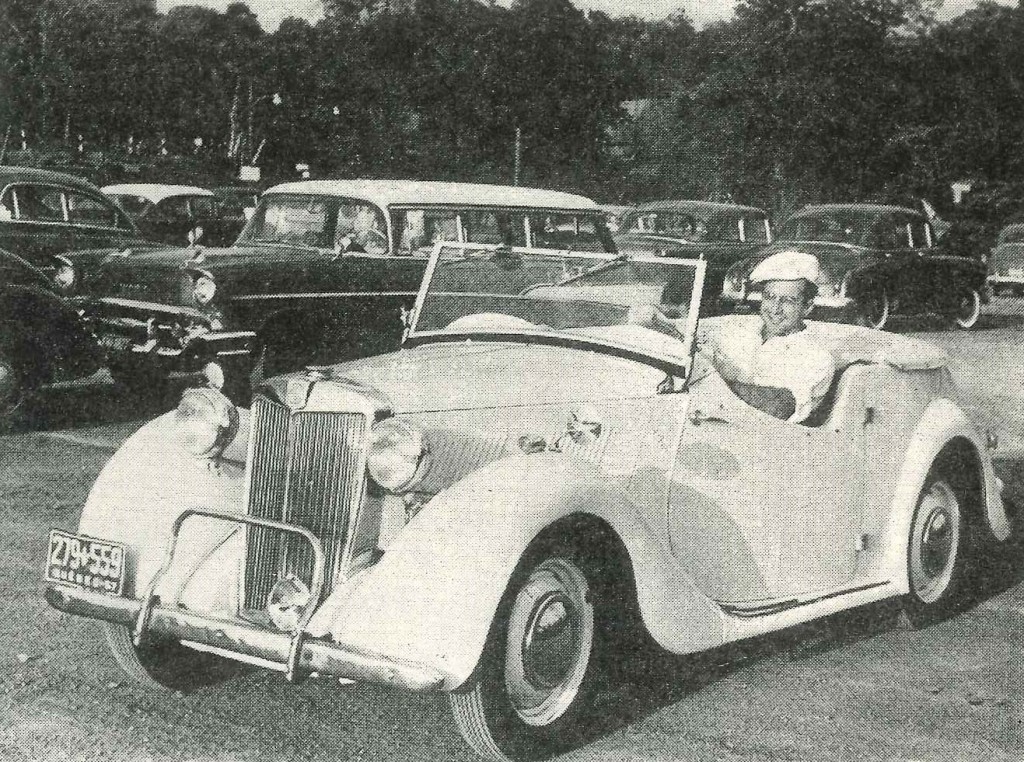

The author with his 1949 Y-type M.G. in Montreal, before the trip to Mexico City, some 2,500 miles away.

The author with his 1949 Y-type M.G. in Montreal, before the trip to Mexico City, some 2,500 miles away.

THE FIRST NIGHT’S CAMP By sheer perseverance we eventually found the way, and as it darkened we started to climb above the valley. We passed through a few silent, slumbering villages on a mediocre track, but by nine o’clock were convinced that we were lost, as the peaks seemed to be all behind us.

A camp was indicated. The rather cool night was disturbed by the back-firing and wheezing of passing trucks, which gave us the impression that we had pitched our tent by the side of a busy highway. We soon realised that tomorrow was Friday—market day—and this track the main transport route for the villages of the area. A damp, uncomfortable morning with breakfast to match, a look at the fuel gauge—despondently low—and a rather vague notion of our whereabouts—these did not combine to spark much enthusiasm in us. A passing truck driver kindly provided 10 litres of gas and a consultation helped us regain our bearings somewhat. The car seemed most optimistic of all, grinding incessantly upwards. We heard an occasional knock due to inferior gas as well as increasing altitude, but this no longer caused concern.

ON THE EDGE OF THE CRATER By noon we reached the 14,000 ft. level. The winding trail emerged from the tree line and passed into barren, boulder-strewn country. The ground levelled, so, assuming that we were just below the summit, we stopped to investigate. Grey and brown rock formations stretched high above us, their peaks invisible in the swirling mist. Our attempts to scale the cliffs were abandoned after climbing about 400 feet with no end in view.

By mid-afternoon we found another route—and finally reached the edge of the crater. A clear bottomless lake, about half-a-mile wide, lay motionless a thousand feet below us. Towering peaks on the opposite side, sheer faces of rock and snow-filled crags dwarfed us as we stood there, trying to adjust our breathing to the rare atmosphere. A steep incline sloped to the shores of the lake, and we made the descent running, jumping and sliding in the soft lava ash.

A roofless dwelling and metal crosses with inscriptions gave evidence of former habitation. Barrenness and silence engulfed us; not even the cry of a bird interrupted. It was an eerie place and we skirted the lake rapidly.

As we were ready to leave we met three Indians walking along a circular track leading into the crater. We exchanged greetings: `Oh yes, Senores, of course there is a shorter way down than the trail you came on. Straight down, just as you leave the crater.’ We returned to the car and decided to continue driving on the circular track towards the crater entrance.

We soon found a passable donkey trail branching off down the mountainside, and assumed it to be the one the Indians had recommended. As we turned down the trail, it descended immediately at such a steep angle that we realised we could not possibly return in case of difficulties. At least this knowledge eliminated all future indecision. Peter shook his head and concluded: `There’s only one way—and that’s down, no matter what happens.’

This was easy stuff: after their adventures on the mountainside, the trio (plus Pepi) had a nice dry river bed to take them towards Zaragosa.

This was easy stuff: after their adventures on the mountainside, the trio (plus Pepi) had a nice dry river bed to take them towards Zaragosa.

The donkey trail soon deteriorated to such an extent that we had to stop frequently to remove stones and boulders, to fill in holes, or to hack away tree-roots obstructing our way. By nightfall we had progressed about one mile downhill. We crawled into our damp sleeping-bags with a continuous drizzle falling on the tent walls and the car perched on a boulder, rear wheels well off the ground.

There was no magic in this forest; no helpful gnomes came to our aid during the night. We awoke to the same picture, and with only slightly revived strength and spirit continued dislodging the indestructible M.G. from obstacles and clearing a passable way through the trees. Our hope of seeing Toluca and civilisation that day received little support; the trees around us were the limit of our vision.

At one instance we seemed to be the sole beings in this vast forest, the next we could distinguish signs of life. A few Indian huts, little, thatched-roof wooden cabins, belching smoke, forlorn-looking in the afternoon mist. We approached. A figure crossed our view; a man covered completely with straw except for sombrero and army boots.

Three men and a car, converging on him from the volcano, were more than he was prepared to accept with equanimity; he turned and fled. We called in Spanish and walked casually, one at a time, after him, abandoning our trusty vehicle for the moment. Finally we shook hands: `Good morning, friend.

How are things here?’ He was reassured. A smile lit up his healthy young face as we admired his straw-thatch coat, which was far more practical than any raincoat, combining simplicity with ventilation. We explained our situation and intentions. The former he accepted without further show of surprise, the latter he amended by pointing out the task ahead of us.

The very first M.G. to scale the slopes of Nevada de Toluca—and a conference to decide how to dismantle and reroute this apparent messenger from the heavens.

The very first M.G. to scale the slopes of Nevada de Toluca—and a conference to decide how to dismantle and reroute this apparent messenger from the heavens.

Before following his advice—to retrace part of our route uphill to reach an alternative and much less hazardous way down—we were happy to accept his invitation to dinner: `To my ranchito, just over the brow of the hill,’ which proved to be a good 2-mile hike over ploughed fields, mounds of rock and various little streams. Finally a group of huts. Walls of boards, tops of thatch, crooked wooden fences, mud in the yard churned by the hooves of goats, sheep and other domestic animals.

A smoke-filled space containing sleeping quarters, cooking utensils, farming implements, sundry belongings and—most important to us—a blazing fire in the middle. Hospitality preceded curiosity. We ate gratefully, watched by our host’s family with a hint of amusement in their wide, dark eyes, as we attempted to manipulate the tortillas (Mexican pan-cakes—staple of every meal) to pick scrambled eggs and potatoes out of the earthenware dishes.

Our friend explained our predicament to the assembly and again it did not cause astonishment, just as our presence and appearance were accepted almost indifferently. An interesting variation in human nature, giving rise to the question whether the free, natural life with its emotional stability, or the devout religious faith which caters abundantly for miracles, is responsible for this—to us—uncommon trait. We parted with thanks and a contribution towards their food budget.

Still firmly convinced that only a down-ward path could save us, we continued against the advice of our host. By this time we were out of fuel again and gravity, with an occasional helping push augmented by boosts from our fortunately healthy battery, was our only source of power.

A few hundred yards more before we admitted temporary defeat. Peter and I headed on foot towards Zaragosa, on a trail which the M.G. might have been able to negotiate after two weeks of road-building and bridging. ‘One hour or so’ had been the optimistic estimate of the trip.

Two and a half hours later we reached the little town—twin steeples projected over adobe dwellings, mud squelched under foot. Pigs, donkeys and people mingled on their various wanderings and errands; caballeros, grouped around tavern doors, looked at us wonderingly.

English sporting caps, plastic raincoats and Lapland boots were not clothes to pass unobtrusively in a Mexican mountain village. We found friendly co-operation in tracking down the sole car-owner and persuading him to part with 10 litres of gas, although our story of an M.G. stranded on the side of Nevada de Toluca must have sounded highly unlikely to him.

As seats and spare wheel are tied to the back of a Mexican pack-horse, a blanket is put over the animal’s head to prevent it taking fright at this unusual cargo.

As seats and spare wheel are tied to the back of a Mexican pack-horse, a blanket is put over the animal’s head to prevent it taking fright at this unusual cargo.

THE THIRD NIGHT OUT We began the laborious way back in the misty twilight, a bag of rolls and a tin of salmon clutched to my damp chest. The 5-gallon can passed from one stiff hand to another. Pepi, the serape-clad, side-burned Mexican sent to accompany us, insisted on the major share of this task.

Whether he was sent with us to safeguard our way, to satisfy the curiosity of Zaragosa’s inhabit-ants, or just to make certain that the 5-gallon can returned to its owner, we never found out. We accepted his company in the same silence in which he offered it to us. The steady drizzle, the endless way into the night, the increasingly heavy can—all combined to have a nightmarish effect on us. We doubted that we were on the right track.

Suddenly a dim light above us and John’s voice: ‘Is that you at last?’ put an end to this weird ascent. John told of an Indian’s visit during his lone watch and of an invitation to his but to spend the night. Anything was preferable to the damp interior of the M.G., the damp sleeping-bags, the damp tent. We clambered up a hill and were met by a similar spectacle as at lunch time. We squatted around the welcome, warming fire, oblivious to smells, animals and smoke around us.

We shared our last food—Nescafe, jam, bread, sugar and salmon—all in silence; again no questions. Pepi of the gas-can was silent too. Our predicament seemed clear enough to all present and no more words were wasted on it. We were invited to settle down for the night. The communal bed, a canvas stretched slightly above the ground between four posts, was cleared of blankets, rags and sundry sleeping children.

The four of us lay down gratefully, crowding the bed to capacity. Little crawling, biting things moved among us; cows and sheep muzzled through the gaps in the wall; donkeys brayed from time to time; our legs became cramped; but at least we were warm and dry. The dawn was hopeful; sunlight filtered through the thatch above us. A frugal cup of Nescafe with our hosts, then back to our task.

By now we had the feeling that we had never done anything but coax my M.G. through the remote forests of Nevada de Toluca. Our only chance was to follow the advice of the locals, who turned out in full force that morning to mount Operation M.G. Leading horses and donkeys, carrying shovels and pickaxes, all were prepared to do battle. They looked formidable. For a moment the thought crossed my mind that we were really at their mercy. I dismissed it.

We had no choice. I turned the car uphill, and, with the help of fifteen caballeros, we reached the first ploughed field. Now every pound of excess weight had to be shed. The M.G. was stripped of everything movable. Spare wheels, side curtains, all the seats except the driver’s, water container, tools.

Within a matter of minutes our helpers had loaded everything on to their horses and made it secure. Peter-20 lbs. lighter than I—took the wheel. With a running start we plunged into the field. I took a movie, fully expecting a sudden collapse, but bouncing and groaning, with engine racing in first gear, the car was pushed across.

Back in comparative civilisation, the M.G. draws up at Zaragosa’s only shop for refresh-ments. Pepi (on the right) is all smiles, but the twin peaks of Nevada de Toluca tower sternly in the background.

Back in comparative civilisation, the M.G. draws up at Zaragosa’s only shop for refresh-ments. Pepi (on the right) is all smiles, but the twin peaks of Nevada de Toluca tower sternly in the background.

MOBILE ONCE MORE I resumed driving on more solid ground—though precariously close to the edge of a gully—four Indians clearing a path in front, Peter filming, and John with the rest of the Indians and pack animals bringing up the rear of the caravan.

The worst seemed to be behind us as we arrived at the beginning of the ‘road’ to Zaragosa. We thought the safari was over. We repacked the car, thanked and paid the caballeros. `Please join me and my family for break-fast,’ our host of yesterday suggested. We watched tortillas being made with stone implements in the age-old fashion and roasted over the open fire.

We really needed them, and also the fresh goat’s milk offered to us. With renewed energy we tackled the last stage, now accompanied only by faithful Pepi, who helped to clear away rocks and roots as I drove at one mile per hour, for this ‘road’ was solely for donkey traffic.

`Not far from here there is a river to be crossed’. Pepi had made one of his rare remarks. Intoxicated with our success up to now, we took no heed. Then suddenly, rounding a little hillock, we came to an abrupt halt at the edge of the stream. Not deep and not wide, but flowing fast and not to be taken in one’s stride. Three housewives, busily beating clothes on rocks, looked up in surprise; they were not accustomed to seeing automobiles driving through their laundry.

Adept road engineers by now, we lost no time building a ramp of rocks below the water’s surface. Only one obstruction in the middle—overcome by jack and sweat—spoiled an otherwise perfect crossing. A steep hill faced us on the other side. Again we unloaded, pushed and heaved, carried the gear up, repacked and continued our journey.

`From here’, Pepi assured us ‘we can all come aboard.’ We followed a dried-out river bed with comparative ease and soon arrived in style in the main street of Zaragosa, our taciturn friend Pepi in the passenger seat, grinning broadly and evidently pleased with his role as man of the hour. The population watched this triumphant entry with interest and suspicion. But when Pepi alighted the scene took on a semblance of reality for them. We returned the gas-can, bought provisions and parted from Pepi.

Though delighted to have no further need of his services, we were sorry to lose his silent, helpful companionship. We drove off along the route of the local bus, accompanied by a guide-cum-hitch-hiker as far as the next village. `This is driving in real comfort’, John said, recalling the past few days which seemed to have lasted an eternity.

Yet it had been only four days since we drove up the volcano on the other side to see a crater, and then spent four days of unforgettable adventure trying to return home. Another guide, another dirt road, another village. Then we saw cars speed by in the distance. Soon we had asphalt under our wheels; a moment we had not dared to imagine in the wet forests 5000 feet above us.

With stubble on our faces, grime on our hands and relief in our hearts we arrived in Mexico City. The M.G. was purring as if nothing had happened and only one slightly dented fender gave evidence of the hardships it had encountered. Only then did I notice that besides an axe, sunglasses and a knife, all my papers were missing. Weeks of bureaucratic tangles were before me.

Without a passport, tourist card or car permit, I was doomed to remain in Mexico for ever—perhaps in hiding in the forests of Nevada de Toluca. G.L.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club