MG’s 4th Racing Year

Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

A dramatic twelve months that made MG history — including a team win in the Mille Miglia and outright victory in the Ulster T.T.

This week’s feature about the amazing feats of MG racing in 1933 was featured in Safety Fast! from April 1961, and was written by William Boddy.

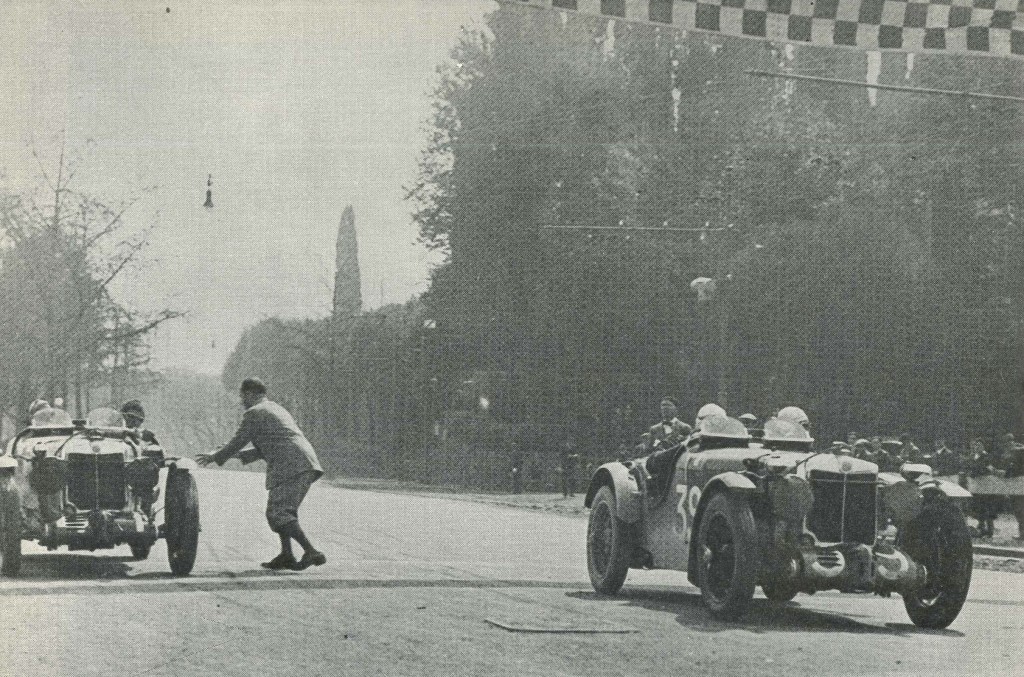

Our heading picture shows a dramatic control stop at Bologna during the 1933 Mille Miglia. An official leaps forward to stamp the Howe/Hamilton control disc as their car screams to a halt. Just a few seconds ahead, the Eyston/ Lurani ‘K3’ is already on its way to-wards Brescia; the two cars finished first and second in their class and won the team prize.

Our heading picture shows a dramatic control stop at Bologna during the 1933 Mille Miglia. An official leaps forward to stamp the Howe/Hamilton control disc as their car screams to a halt. Just a few seconds ahead, the Eyston/ Lurani ‘K3’ is already on its way to-wards Brescia; the two cars finished first and second in their class and won the team prize.

By the close of 1932, the third season in which MG had competed in motor races, the cars from Abingdon were long past mere struggling for recognition—they were the accepted leaders of their class. Not only had they won many important racing victories during 1931 and 1932, but every International Class (1-1′ – up to 750 c.c.) record was in their possession.

Moreover, just before Christmas 1932, George Eyston had given MG the distinction of producing the first 750 c.c. car to exceed a timed speed of two miles a minute. All this was exceedingly satisfactory. It served not only to sell MG sports cars in large numbers to discerning enthusiasts who craved a race-bred model, but also drew useful attention to the Morris Minor, a popular baby car of the day, from the original design of which had stemmed the first MG Midget.

The year 1933 marked the opening of what might be described as the second phase of MG racing history, for now the supercharged MG Magnette made its debut. At this time Earl Howe, President of the British Racing Drivers’ Club, was prominent in the motor-racing firmament at the wheel of Bugatti, Mercedes-Benz and Alfa Romeo cars but, like his contemporary, Sir Henry Birkin, Bt., and Stirling Moss many years later, he drove foreign racing cars only because there was no suitable British product.

Now Howe looked closely at Cecil Kimber’s MG Magnette—the unblown model of late 1932—and decided that he was justified in a change of policy. In making this decision there is no doubt that Howe had been influenced by the splendid racing and record-breaking achievements of the MG Midgets in former years.

He had set his heart on seeing a team of British sports cars competing in the 1933 Mille Miglia, a race akin to the great town-to-town contests of a past age which died with the ill-fated Paris-Madrid race of 1903. This great Italian open-road race was beginning to attract attention in England, and Howe had watched the 1932 event, in which Lord de Clifford had started with an MG Midget but, after a fast run, had been obliged to withdraw at three-quarters distance when the drive to the overhead camshaft sheared.

The race was won that year by Alfa Romeo at an average speed of 68 mph, and the 1100 c.c. category was dominated by potent little Maseratis. In the new MG Magnette, Earl Howe saw a suitable means of proving the supremacy of British small sports cars in 1933. He put his proposition to Cecil Kimber, the support of Lord Nuffield, Governing Director of the MG Car Company, was secured, and Howe was free to discuss the proposition. Kimber was rightly cautious.

He argued that no Magnette had so far been raced, that the car in supercharged form was still experimental (only one had been built) and that to put up a team of three completely untried cars against the well-established Maseratis might well end in fiasco.

E. R. Hall, in his long-tailed ‘1(3’ Magnette, wins the gruelling B.R.D.C. 500 Miles Race at Brooklands at an average speed of 106.53 mph.

E. R. Hall, in his long-tailed ‘1(3’ Magnette, wins the gruelling B.R.D.C. 500 Miles Race at Brooklands at an average speed of 106.53 mph.

HOWE MAKES AN OFFER It was then that Howe proved he was not just a wealthy patron of the sport, seeking an easy means of securing an entry in the Mille Miglia. Kimber’s justifiable doubts he countered with a practical plan of action. Howe asked that one blown Magnette be built as a practice car, in whichhe could go out early in 1933 and drive over as much of the 1000-mile course as winter conditions would allow.

If the result proved promising a team of three cars would be prepared for the race and lent to him, on the understanding that he met the considerable expense of entering the cars and transporting them to Italy and back to England. This plan proving acceptable, work went ahead on the Mille Miglia practice car. The six-cylinder, four-bearing 57 X 71 mm. engine was supercharged with a No. 9 Powerplus compressor mounted in front of the engine, which had pump cooling, magneto ignition and Ki-gass as an aid to starting.

On the test bench this power unit gave over 100 bhp on a hasty run-up. It was installed in a chassis having a pre-selector gearbox controlled by a normal-looking MG gear-lever, this form of quick-change box having been used by Sir Malcolm Campbell in his rebuilt 4-litre V.12 Sunbeams, as it was later to be adopted for the first of the successful E.R.A. racing cars.

Speed was the watchword in building this Magnette, because Earl Howe wanted his team to assemble in Milan on 19 January, conscious that this left very little time before he hoped to have three Magnettes on the starting line for the race in April, a bare twelve weeks later. A further test of the new design was arranged by entering the earlier ‘K3’ prototype, a short-chassis model, in the Monte Carlo Rally starting on 21 January.

Earl Howe’s team must have been greatly encouraged when the news filtered through to them in Italy that this first prototype had not only finished the ‘Monte’ route without trouble, but had put up the fastest time of the day in the Mont des Mules hill-climb after the event. Howe had picked his drivers with care and they represented the elite of the British gentlemen ‘speed kings’. Indeed, they were all experienced in road as well as track racing.

Sir Henry Birkin was to be partnered by Bernard Rubin, George Eyston was to share a car with Count Lurani, who was experienced over the Mille Miglia route, and as his own co-driver Earl Howe nominated Hugh Hamilton. His Lordship spared no expense over the practice period; he took out not only the Magnette but an Alfa Romeo and a big Mercedes Benz. The latter car was to carry spares and supplies and it was an ingenious move to enter it for the actual race, so that this travelling ‘spares department’ could follow the MG team round the course!

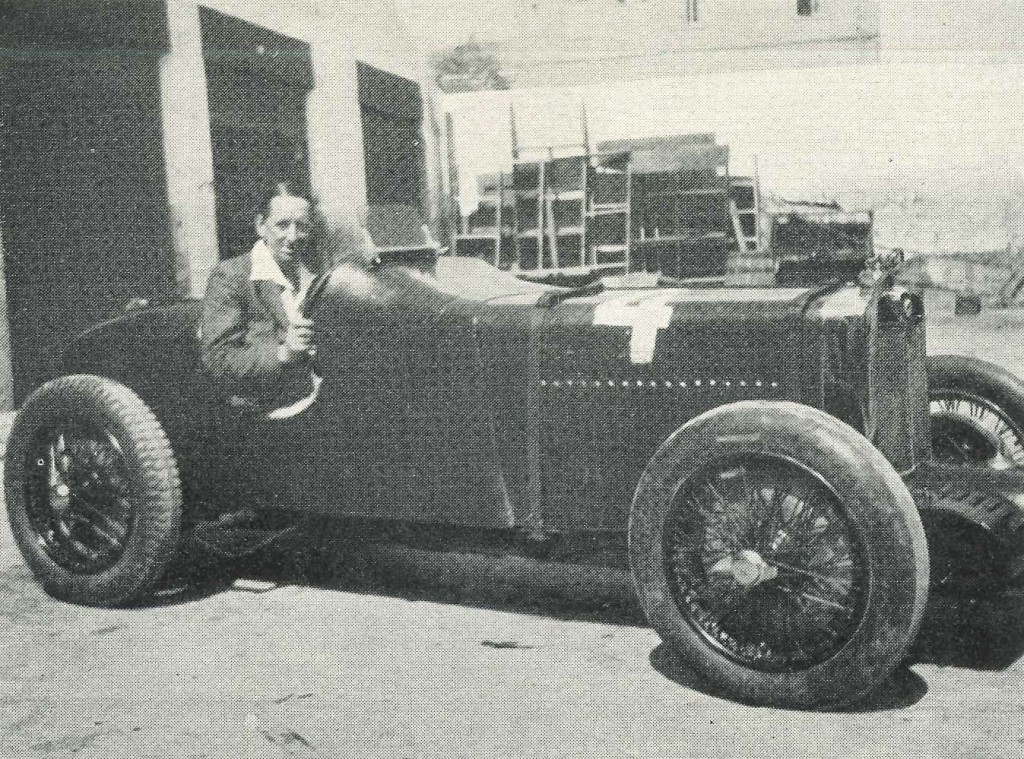

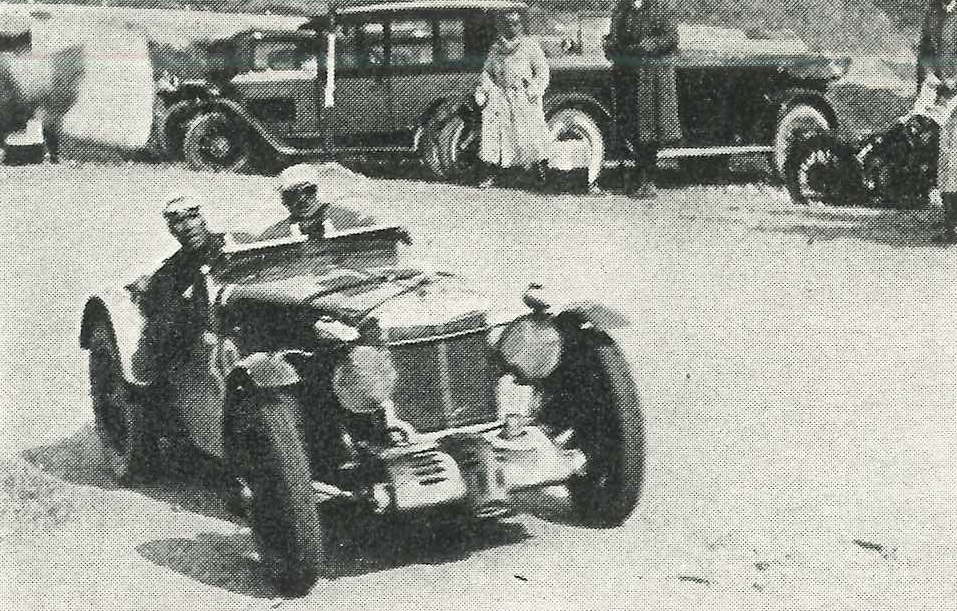

Whitney Straight took this 2-seater ‘K3’ Magnette (his mechanic is in the cockpit) to Pescara and won the Coppa Acerbo Junior against all the local monoposto Maseratis.

Whitney Straight took this 2-seater ‘K3’ Magnette (his mechanic is in the cockpit) to Pescara and won the Coppa Acerbo Junior against all the local monoposto Maseratis.

PRACTICE BEGINS A week before the Milan rendezvous, R. C. (`Jacko’) Jackson drove the green Magnette to Newhaven an exciting-looking car with blower hidden under the front dumb-iron cowl, from which the S.U. carburetter protruded, simple two-seater body with slab tank behind (the shapely racing bodies did not appear until. 1934), fixed cycle-type wings and external exhaust system along the near-side.

The main windscreen folded flat, twin aero screens then being used, and the huge brake drums behind centre-lock wire wheels stamped these MGs as business-like racing machines. At Newhaven `Jacko’ joined up with Earl Howe and Thomas, his mechanic, in the blue Alfa Romeo and the Mercedes Benz.

For the run to Nancy the Magnette was loosened up by running at 60-65 mph, when it returned 18 m.p.g. The next day Howe called at the Bugatti factory, and when the great Ettore looked at the Magnette he remarked on the frailty of its front axle.

So much weight did Bugatti’s opinion carry that this was later re-designed. On the final day’s journey the cars were entrained through the St. Gott-hard tunnel and the weather… was so cold that restarting was difficult, even after hot water had been used to refill the radiators. Greatly hampered by such conditions, the Magnette was nevertheless subjected to enough testing for many points requiring rectification to show up and eventually it was brought home to Abingdon.

With a space of only twenty days before the cars were due to leave for Italy, the erection of them commenced and proceeded with unfrenzied haste. There were bearing and gasket troubles to be overcome after engine bench tests, which were the more worrying because the first engine tested gave only 72 bhp at 4,500 r.p.m. or four horsepower less than the prototype at that speed.

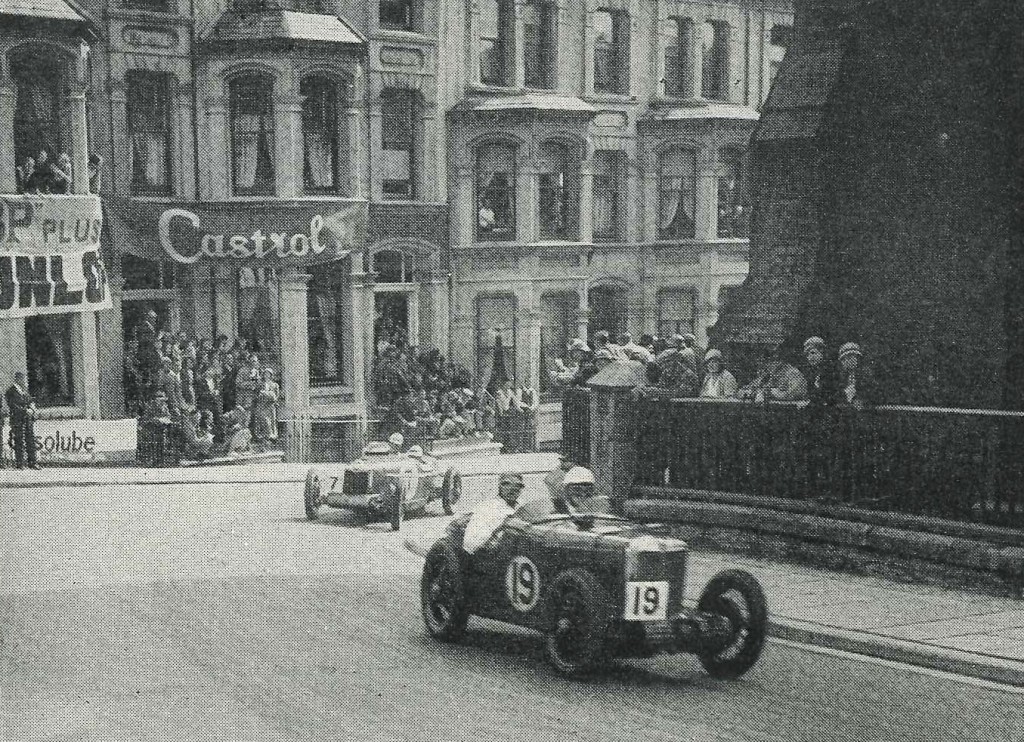

Real road racing! Round the houses on the Isle of Man during the Mannin Beg race. S. A. Crabtree leads Freddy Dixon’s Riley into Church Road; this was not a successful event for M4., Dixort eventually winning, with Mansell’s MG Midget the only other finisher!

Real road racing! Round the houses on the Isle of Man during the Mannin Beg race. S. A. Crabtree leads Freddy Dixon’s Riley into Church Road; this was not a successful event for M4., Dixort eventually winning, with Mansell’s MG Midget the only other finisher!

Eventually, however, the cars were completed, given a brief run round the factory roads, then put on a train for Fowey in Cornwall, whence they were crudely shipped in a cargo vessel to Genoa. Howe had taken the practice Magnette by road, accompanied by Mercedes, Alfa Romeo and a lorry.

Back at the MG factory, those left behind could relax; `Nobby’ Marney, for one, had worked 73 hours without sleep to see the Mille Miglia Magnettes on their adventurous way. No-one could have been under any delusion as to the formidable task faced by these green MGs. The 1933 Mille Miglia had attracted an entry of 98 cars, of which only Howe’s and Brauchitsch’s Mercedes were other than Italian; moreover, the Magnettes faced the fast 1100 c.c. Maseratis,

Whitney Straight took this 2-seater ‘K3’ Magnette (his mechanic is in the cockpit) to Pescara and won the Coppa Acerbo Junior against all the local monoposto Maseratis.

which had been tested repeatedly over the actual course. However, there was no turning back now, and, under the team manager, Hugh McConnell, famous Brooklands scrutineer, practice commenced, drivers and mechanics determined to learn everything possible about the job that lay ahead.

There were fuel consumption tests to make, the refuelling depots to lay out and, at the last minute, McConnell discovered that the regulations called for silencers, which had to be made on the spot with Italian labour, because up to then straight-through pipes had been bellowing their war-cry. After Hamilton had run out of road at night he is said to have put a 75-watt bulb in one headlamp, a 50-watt bulb in the other, after which he was able to see half-a-mile ahead!

One of MG’s greatest wins was the 1933 International Tourist Trophy, which the renowned Tazio Nuvolari won out-right with a ,K3. Magnette, illustrated here by this F. Gordon Crosby drawing (below). Nuvolari is seen (right) at the pits before the race, with his wife.

One of MG’s greatest wins was the 1933 International Tourist Trophy, which the renowned Tazio Nuvolari won out-right with a ,K3. Magnette, illustrated here by this F. Gordon Crosby drawing (below). Nuvolari is seen (right) at the pits before the race, with his wife.

SUCCESS IN ITALY So race day dawned, and now it was up to the drivers to repay the work of the faithful mechanics and the technical staff back at home at Abingdon. As had often been the case when he was driving Bentleys, Birkin was set to make the pace, in the hope of breaking up the Maserati opposition. In this he was successful, for his MG set up new class records for the first 235 miles to Siena, his average speed being 61.7 mph.

The engine had lost its tune, a valve having burnt out, but although this Magnette had to retire it had achieved its object. Tufanelli’s Maserati was also out, with gearbox failure, and the other Maseratiwas running 40 minutes behind Howe. Eyston and Lurani were thus leading their class and Howe’s MG was going satisfactorily. Lurani averaged 58.2 mph to Rome, a distance of 365 miles.

At Terni, Eyston was behind the wheel, the average was up to 58.7 mph and Howe was catching up. As they reached Bologna he was a mere two minutes behind the other car, having touched over 100 mph where possible during the night, and having driven continuously for some twelve hours. So the two British cars raced on. They had to stop frequently for fresh plugs (Eyston and Lurani are reputed to have changed 157) but they had out-run all opposition.

The Eyston/Lurani MG won the class at 56.89 mph and the Howe/Hamilton car was second, 90 seconds behind, a performance which won MG the Team Prize. Never before had this trophy, the Gran Premio Brescia, gone to a non-Italian team. I have dealt with the 1933 Mille Miglia at some length because I rate it as one of the finest British achievements in pre-war racing.

For the `K3′ Magnettes to do so well on their initial appearance, far from home, showed the worth of these very genuinely race-worthy cars. Capable of exceeding 110 mph in road-trim, these Magnettes were phenomenal for cars built nearly 30 years ago and have caused no less an authority than John Thornley to remark that perhaps the science of automobilism has not progressed so very far in the intervening years.

THE MAGNETTES AT BROOKLANDS Back in England, attention was turned to the ingenious J.C.C. International Trophy Race at Brooklands, handicapped by artificial corners of varying severity instead of by mathematics. Two of the Mille Miglia MGs were entered, to be driven by Howe and Mrs. Wisdom, and production `1(3′ Magnettes were handled by E. R. Hall and G. F. Manby-Colegrave. Apart from these four 1100 c.c. MGs there were eight MG Midgets running, including Eyston’s famous 120 mph ‘Magic Midget’ and Ron Horton’s red single-seater which had won the 1932 500-Mile Race.

Yallop actually entered a 1930 ‘Double Twelve’ Midget. Hamilton had hoped to run his blown T.T. Midget, but a very nasty experience befell him in practice when the prop-shaft broke to high speed. He managed to hold the car and escape serious injury but the MG could not be repaired in time to start. It proved a devastating race in which only eight cars finished.

The Hon. Brian Lewis won in an Alfa Romeo, but the MG Magnettes finished second, third and fourth, in the order Hall, Mrs. Wisdom, Howe. Manby-Colegrave hit a sand-filled marker tub and damaged a front wheel. All the Midgets had to retire, Yallop’s old car being left on the starting line with selector trouble, Eyston losing a wheel, Elwes crashing, Horton experiencing clutch failure and the remainder having engine trouble, mainly big-end failure.

However, Horton off-set his defeat in the International Trophy by winning his class in the Midget at Avus, and Hamilton did likewise at the Niirburgring. Back at Brooklands, Manby-Colegrave finished third in the B.R.D.C. Empire Trophy Race, averaging 106.88 mph Horton, who had also taken delivery of a `1(3′ Magnette, track-bodied like his very fast Midget, set a new class Outer Circuit lap record of 115.55 mph to finish fourth.

Drawing by courtesy of ‘The Autocar’.

Drawing by courtesy of ‘The Autocar’.

FAILURE .. . Some really exciting racing was expected when the R.A.C. agreed to hold the Mannin Beg and Mannin Moar races over a road circuit in the Isle of Man. The 4.6 miles of public roads closed for the occasion provided a tough course, very attractive to motor-racing folk, but not popular with holiday-makers when they found the promenade at Douglas closed to them while racing was in progress.

In the ‘Beg’ or small-car race, Midgets and Magnettes were on an equal footing. Eyston, Hall, Yallop, Mere, Rubin and Hamilton entered Magnettes, Rubin nominating Kaye Don as his driver. MG Midgets were to be driven by Ford and Baumer, who had brought their little car home in sixth place at Le Mans, Mansell, E. L. Gardner and Crabtree.

Don’s car developed back axle trouble in practice, although making fastest lap at 60 mph, and this was the foretaste of similar trouble that eliminated three of the Magnettes from the event. The blown engines and pre-selector gearboxes had proved too powerful for the two-star differentials on the tortuous Isle of Man circuit, although satisfactory under the rather different conditions of Brooklands or the Mille Miglia.

The Magnettes of Mere, Yallop and Hamilton had succumbed to axle failure and the other three had also retired, Eyston’s with a broken drive-shaft to the camshaft, Don’s with valve trouble, while Hall’s crashed too badly to continue.

Indeed, the Manin Beg had proved a punishing event, for only two cars did complete the course, Dixon’s Riley winning at a crawl because all its oil pressure had vanished on the last lap and Mansell’s MG Midget taking second place before the time-limit expired. Baumer’s Midget, also flat out, was flagged off. Dixon had averaged 54.4 mph, which proves that it is not necessarily the fastest races that cause the most retirements.

ANOTHER ITALIAN SUCCESS After Hamilton had enjoyed some hill-climbing successes in Germany with his Midget, Whitney Straight took a ‘1(3’ MG Magnette he had bought as a chassis, having a conventional two-seater racing body fitted to it at Brooklands by Thomson and Taylor, put it on a trailer, and got his chauffeur to tow it to Pescara. Here he surprised the natives by winning the Coppa Acerbo Junior race at 75.4 mph from the local Maseratis.

Barbieri was so soundly beaten that a protest was lodged, and Straight was not awarded the race until the engine of his Magnette had been measured and found to be of 1087 c.c. Straight had proved a two-seater single overhead-camshaft MG to be faster than single-seater twin-cam Maseratis on their own ground.

SUCCESS IN IRELAND The next race of importance in which the Magnettes were entered was the Ulster T.T. in Ireland. By now a four-star differential had been incorporated and Hall and Yallop were down to drive their Mannin Beg cars, Manby-Colegrave his International Trophy car and Straight his successful Coppa Acerbo machine. In addition, eight MG Midgets were in the list, including Hamilton’s. Doctor’s orders eventually rued out Straight but this enabled Kimber to nominate a works car for none other than Tazio Nuvolari, the greatest racing driver of all time, to drive.

The story has been told so often, by myself as well as others, that it suffices to say that Nuvolari, after he had discovered what a pre-selector gearbox was all about and had adjusted the shock-absorbers to his fancy, won the T.T. It was an extremely close finish; because the handicap worked in favour of Hamilton and only by driving at his brilliant best did the little Italian get the Magnette home 40 seconds ahead of the MG Midget.

On their way up the Futa pass during the Mille Miglia, Count Lurani (at the wheel) and George Eyston make sure of their class win in this gruelling Italian road-race.

On their way up the Futa pass during the Mille Miglia, Count Lurani (at the wheel) and George Eyston make sure of their class win in this gruelling Italian road-race.

Nuvolari averaged 78.65 mph and covered his last lap at 80.35 mph, while Hamilton had averaged 73.46 mph Hall’s Magnette was fourth, Manby-Colegrave’s seventh. Nuvolari’s drive is one of motor racing’s epics. Even had there been no handicap operating for this Ulster race, he would have come within 0.06 mph of winning, for this was the margin under that of the fastest car in the 1933 T.T., Rose-Richards’ supercharged 2.3-litre Alfa Romeo, which finished in third place.

Hounslow, the MG mechanic who had the privilege of riding with Nuvolari, has recounted how the Italian ace worked methodically at pit-stops and of how he flung the cart-sprung MG into corners, scarcely using the brakes. Nuvolari had broken the class lap record for the Ards circuit no fewer than seven times.

Obviously he appreciated the need to hurry, yet he never drove the Magnette above its limit, was even able to nurse it in the early stages of the race, and he found time during the pit-stop to check personally the tightness of the hub nuts that Hounslow had just replaced. True, if Hamilton had not needed more fuel at the very end Nuvolari would have been second, but ‘ifs’ are of academic interest only, in motor racing…

VICTORY AGAIN! The 1933 season ended with an MG victory of another kind, when the methodical E. R. Hall had his T.T. Magnette fitted with a higher axle ratio and a long-tailed single-seater body and, purposely holding its lap speed to 110 mph, marched through that B.R.D.C. track marathon, the 500-Mile Race at Brooklands, until all the opposition had faded away, even Dixon’s Riley, and his MG could tour round at 102 mph to win what was then the most punishing race in the world, at 106.53 mph.

Not only had the MG’s engine proved able to withstand hours of wide throttle work but its chassis had stood up to the fearful pounding imparted by Brooklands’ battle-scarred surface. That this was no fluke was shown when Charlie Martin’s MG Magna came over the line in second place, Yallop’s Magnette in fifth position and Wright’s Magna still running when the course was closed. Eyston had set the pace to start with, the Magic Midget averaging 112 mph but a trifling fault in the ignition distributor had caused its retirement.

MORE RECORD-BREAKING Eyston’s disappointment was off-set by the knowledge that in the course of practice, while fuel consumption was being checked, he had been able to re-take three Class ‘H’ records that Driscoll’s Austin had wrested from MG. These were the 50-kilometre, 50-mile and 100-kilometre records, which on this nonchalant run Eyston retrieved at speeds of 105.76, 106.67 and 106.72 mph respectively.

This again gave MG every record in Class ‘H’, but Austin hoped to snatch back at least some of them. Seeing this, Eyston wound up the 1933 season by taking the Magic Midget to Montlhery with an even narrower body than had been used previously, so that only little Albert Denly could squeeze into the cockpit. In this low-drag MG, Denly put the flying-start kilometre and mile Class records to the astonishing figure, for a 746 c.c. car, of 128.62 mph.

He also set the 5-kilometre and 5-mile records to over 128 mph, the 10-kilometre record to 127.45 mph and the 10-mile record to 125.56 mph This was too fast for the Austin, but it set about trying for the hour record. It failed to gain this because the fuel tank came adrift, but the 50-kilometre record was broken.

So Denly squeezed into the MG once more and lifted that record and a few others out of temptation, a splendid run ending with the 750 c.c. hour record at 110.85 mph And, remember, all this happened, my children, over a quarter of a century ago . . . I have the greatest admiration for these MGs of 1933.

If Napier and Sunbeam effectively ‘wore the green’ in the early days of motor racing, and Bentley put our cars on the map of Europe with their Le Mans victories in vintage times, the convincing successes achieved by drivers of the calibre of Howe, Birkin, Hamilton, Straight and, not least, Nuvolari, demonstrated to the world the supremacy of Britain’s small sports cars, the fame of which has never since waned. W.B.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club