Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

National Treasure

Part 1 – The development and history of the MG 6R4

By Martyn Morgan Jones

In 1982, FISA (Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile) restructured the rules for international rallying. And this wasn’t some simple rethink: it was a sea change. Crucially, from 1983, Group 4, previously home to the fastest cars, would make way for Group B: a fire-breathing, no-holds-barred category that would come to epitomise the hedonistic excesses of the 1980s.

In penning the new regulations, FISA had been uncharacteristically charitable. Only 200 identical, road-going, examples had to be built within a 12-month period. As long as these were produced, FISA would sanction the building of a further 20 ‘evolution’ cars: cutting-edge creations, built purely for rallying, with few restrictions in terms of technical development and materials. International rallying was about to enter a period punctuated by bouts of technological frenzy and innovation.

This new breed of artisan-built cars, some benefitting from Croesus-like resources, bore a passing resemblance to their road-going counterparts. But, beneath the skin, they had almost nothing in common.

Four-thought

The new rules were not the only sea change. So, too, was the arrival of the Quattro. Although a rallying newcomer, through its adoption of permanent four-wheel drive, Audi was pointing the way forward. And, it must be remembered, this was some two years prior to Group B’s inception.

Finnish rally ace Hannu Mikkola, after just 30 minutes behind the wheel of a Quattro, stated: “I have just experienced a convincing view of the future. Quattro will change the rally scene once and for all.”

Even so, some manufacturers still considered four-wheel drive to be too heavy, and too complex to be viable. Seemingly, at this stage, thanks to the efforts of its Director of Motorsports, Jean Todt, only Peugeot Talbot had truly grasped the significance of four-wheel drive. Todt, astonished by the Quattro’s devastating ability, especially on the 1981 RAC Rally, persuaded Peugeot Talbot that their next rally car had to be four-wheel drive. As it transpired, Austin Rover would soon be similarly moved.

John Davenport, Director of Motorsport at Austin Rover, planned to replace the recently retired TR7V8/TR8 with something akin to Ford’s RS1700T. However, following discussions with Patrick Head, Williams’ Technical Director, and the arrival of the Quattro, the design underwent an about turn. Literally.

“The whole 6R4 thing actually stemmed from a number of conversations I had, particularly with Patrick,” recalls Davenport. “In December 1980 we were at Paul Ricard Circuit, testing differential settings on the Rover Vitesse race car. The only reason we were able to test there was because Williams Grand Prix Engineering had hired the circuit. British Leyland was one of Williams’ sponsors at the time. I mentioned to Patrick that we were planning to do something with the new Metro, making it our next rally car, and asked if he’d have a look at it. I went on to say that we were considering rear-wheel drive, with a rear-mounted transaxle. We also touched upon the Quattro, which had just been released on the European market.”

The Quattro proved to be a rallying revelation and Mikkola’s prediction for the sport’s future was soon being borne out on the world stage. In 198 on its first outing, the Jänner Rallye, the Quattro triumphed. It went on to win a couple of World Rally Championship rallies. Audi garnered additional, and eye-catching, exposure when the delectable Michèle Mouton won the 1981 Rallye Sanremo. The significance and efficacy of the Quattro’s drivetrain was not lost on an increasing number of motorsport’s movers and shakers, including Patrick Head.

“Until April/May 1981, we were still progressing along the lines of a front-engined, rear-wheel drive design,” explains Davenport. “Of course, 1981 was the year the Quattro really started to perform. Patrick suggested we go along the four-wheel drive route. This had been in my mind, too.

“The change of direction started mid-1981, and from there on it was all hard graft. But, I was patently aware of the fact that it would have been impossible to undertake such a specialised VHPD (Very High Performance Derivative) project at Austin Rover. Thankfully, Williams agreed to collaborate. Williams not only had the engineering capacity, it also had the flexibility…and the expertise, of course. The key man at this stage, and who remained pivotal throughout, was George Koopman: Williams’ Finance Director. Somehow, George and I managed to accrue enough money to get the project underway.”

If started a year or so later, it would have been possible to base the project around the Maestro, a much easier car to package for rallying…and to convert to four-wheel drive. But the Maestro was still some time away from entering production. Anyway, marketing and in-house politics dictated that the new rally car be based on, and be reminiscent of, the diminutive and volume-selling Metro. Davenport, albeit appreciative of the Metro’s size constraints, put a positive spin on things when he later declared that “a small car makes a small track look bigger!”

It was certainly on the small side, but the rally project, even with collaboration from companies such as Williams, was most definitely a large ask for the newly formed Austin Rover, a company that was in its unwieldy corporate infancy.

“It was a slow job in many, many ways,” admits Davenport. “Money was always in short supply. In the early days, no-one in the company would readily open their chequebooks. We had to make do with what we could squeeze out of the motorsport budget. And, when we moved from Abingdon, in 1982, we had an enormous sale and sold off all of the Special Tuning bits. Then Harold Musgrove took over from Michael Edwardes. Under Musgrove, we were given more importance, budgets became a little healthier. We went from being the poor relation, to being relatively well funded. Not that we had the kind of sums Todt had at Peugeot Talbot, of course! But we were certainly in a much better position.”

In a better position…and with much of its focus being engine-related. “During the project’s very early days, we’d briefly contemplated fitting a Rover V8,” mentions Davenport. “Of course, it was far too large, too heavy and would have affected weight distribution and packaging.

“Thoughts then turned to the soon-to-be-introduced Honda Legend/Rover 800 V6 engine. However, we discovered that it was a SOHC design with long rockers and very much a road engine. It was never going to produce the power needed. We then asked Honda for information on their 2-litre Formula 2 engine. They sent us all of the parameters. Unfortunately, it was so over-square, and had a very narrow power band. To make it competitive for rallying would have necessitated a huge amount of re-engineering.”

Motivation

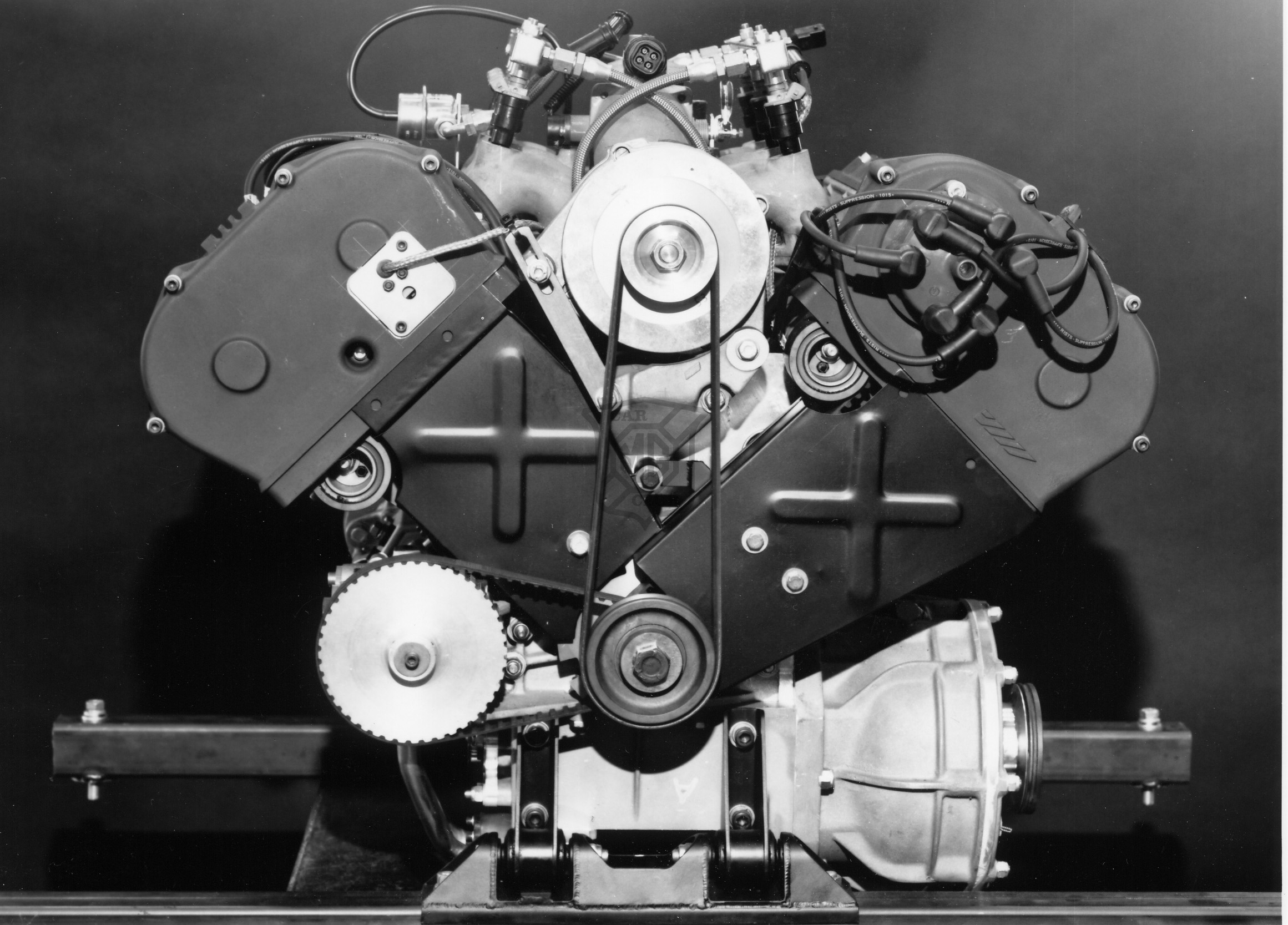

The only solution was to design a bespoke unit; a task that was entrusted to David Wood, Austin Rover Motorsport’s Chief Engineer, and his newly appointed team. The decision was also taken to make it a normally-aspirated engine, thereby avoiding the turbo lag and heat issues that were then typical of turbocharged engines. Turbocharging had been discussed, but it was felt that in such a small car a normally- aspirated engine would do the job admirably. Plus, neither Austin Rover nor Honda had any engine that was vaguely suitable for turbocharging.

“David started work on designing the engine immediately,” cites Davenport. “Nevertheless, we were in urgent need of a slave engine to enable us to test the prototypes Williams was building. To facilitate this, David lopped two cylinders off a Rover V8, creating a 2.5 litre V6, dubbed the V62V. The target was 200bhp, but it actually produced 250bhp.

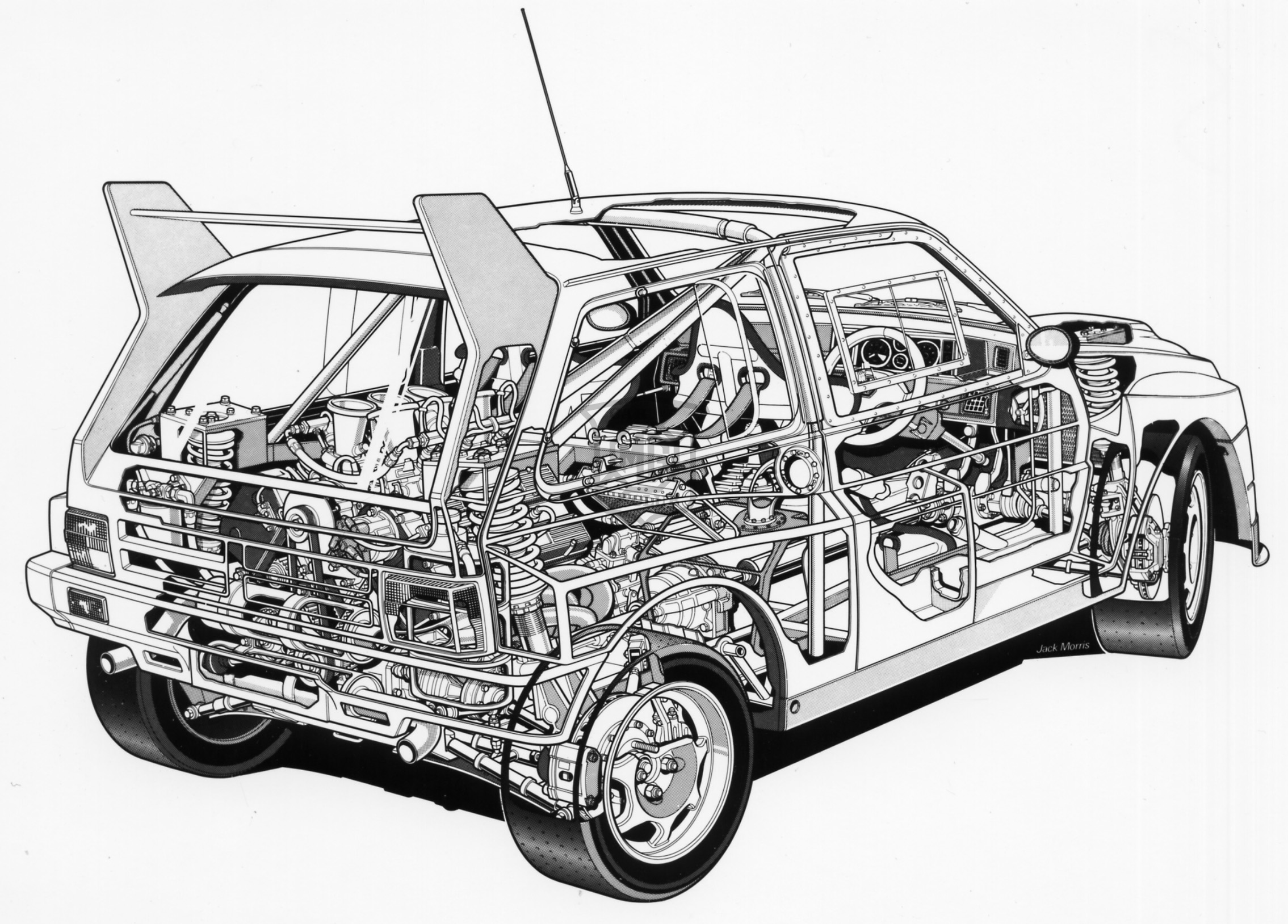

“Williams had been very busy too, and three prototype/development cars had been produced, two in kit form and one, effectively the concept car, being fully built and operational, complete with a V62V engine. They were delivered in February 1983. Brian O’Rourke had done a terrific job of designing the monocoque, which had been built by Johnny West, Ian Anderson and Derek Jones. The floorpan had been cleverly fashioned into what was effectively a seam-welded tubular chassis and the roll cage was built-in. A fourth shell was later made and this was handed over to us in September 1983.”

The first 6R4 (six cylinder, four-wheel drive), chassis, 001, was tested at Chalgrove Airfield, Oxfordshire, in February 1983. John Piper, Design Engineer at Williams, instructed by Patrick Head, drove the car for the first 200 miles before it was handed to Tony Pond for further testing (although Steve Soper drove it once when Tony was ill).

This testing, and subsequent development, ate into the schedule, which explains why Austin Rover Motorsport didn’t unveil its most-gifted rally progeny until February 1984. Only then, confident that it had a potential winner, did the team go public. The ‘reveal’ of the MG Metro 6R4 took place at the Excelsior Hotel, London, where the paparazzi and guests witnessed Tony Pond drive through a pseudo film screen. Painted classic red with white roof, it was redolent of the works Mini Coopers and Austin Healeys.

This testing, and subsequent development, ate into the schedule, which explains why Austin Rover Motorsport didn’t unveil its most-gifted rally progeny until February 1984. Only then, confident that it had a potential winner, did the team go public. The ‘reveal’ of the MG Metro 6R4 took place at the Excelsior Hotel, London, where the paparazzi and guests witnessed Tony Pond drive through a pseudo film screen. Painted classic red with white roof, it was redolent of the works Mini Coopers and Austin Healeys.

Aero Pack

Much of 1983 would be spent testing at Chalgrove, Cadwell Park, and MIRA. Gradually, the 6R4’s specification and performance were honed. Most obvious was the way in which its appearance changed. Even allowing for the wider wheelarches, the first iteration was not too far removed stylistically from a production Metro. The soon-to-be-adopted aerodynamic package changed all of this. More importantly, the difference the wings made to the car’s stability, and handling, was significant.

“The initial aerodynamic improvements came about during 1984, at the suggestion of Patrick,” recalls Davenport. “Williams had huge experience with aerodynamics, of course. We weren’t convinced at first though.”

What convinced Davenport and his team was the feedback received from Tony Pond after testing a ‘be-winged’ 6R4 at Oulton Park. John Piper picks up the story. “Aerodynamics was everything to Williams. Patrick had suggested we fit wings to the 6R4, but Austin Rover wasn’t convinced. So, Brian O’Rourke had a rummage around in one of Williams’ old storerooms and found a rear counterflap, the part that’s attached to the trailing edge of the main wing. It was from a FW06 F1 car and approximately the same width as the Metro’s rear hatch. Brian sketched out some crude wing endplates and made them in 10-gauge aluminium sheet to fix it to that rear hatch. Patrick thought the wing would do fine.

“When Tony brought the car in from its first testing session we showed him the wing. He fell about laughing! However, we persuaded him to give it a go…and he was immediately lapping a few seconds faster. But he complained that the car had terminal understeer due to the extra rear grip. So, we dived into our van and pulled out a front splitter which we’d cobbled up from a sheet of aluminium. This was attached to the 6R4, Tony did more laps, and was a few seconds faster still. He raved about it…and subsequently convinced Austin Rover to add an aerodynamic package to the 6R4. Which, thanks to Bernie Marcus, Austin Rover’s excellent aerodynamicist, they did. The car ultimately became much more stable…and much quicker.”

Changes

In what was a rather bold move, Austin Rover Motorsport announced plans to test the car under competition conditions, ie national rallies. True to its word, the team entered a 6R4 on the 1984 York National Rally (but without the aero package – this first appeared in public on the 1984 Mewla Rally). Having posted fastest times on eight of the 11 stages, and leading by almost three minutes, the alternator cremated itself, bringing the 6R4 to an untimely halt. The team planned to withdraw Pond at the end of the event, as he was needed at Silverstone to qualify his Rover Vitesse in the British Saloon Car Championship.

Alternator woes aside, there was no doubting that the 6R4 had the makings of a world-class rally car and further competition outings would accelerate its development considerably.

As development gathered speed, and boundaries approached, the umbilical tie between production Metro and rally sibling was stretched to its limit…then severed. In the end, the only familial commonalities were the front grille, windscreen, headlamps, and part of the doors. In total, only 16 panels/parts were carried over. It’s been said that the remaining 347 are unique to the 6R4.

The car had grown in stature too…and not just in terms of its rallying prowess; it was much better endowed physically. The front and rear suspension, John Piper’s handiwork (he was responsible for the steering rack’s design too) had been relocated, stretching the wheelbase by 5 1/2 inches in the process; the track was wider and the struts were four inches taller. The reason behind the changes? Tyre availability.

“At this stage, we were still using 13in wheels,” recalls Davenport. “Pierre Dupasquier, Head of Michelin’s Competition Department, mentioned that if we turned up for the Monte Carlo Rally on 13in wheels, he could only supply road tyres. If we wanted Michelin’s competition tyres, the ones developed for Audi and Peugeot, this would require 390mm (a smidge bigger than 15in) wheels. We had no option other than to re-engineer the 6R4.

“Bernie Marcus also had to redo all of the aerodynamics. Interestingly, we’d fitted NACA ducts to the rear side windows, to draw hot air from the engine compartment. But, when Bernie did his assessments, he found that they were actually pushing air in! At this stage we were still using the V62V engine. This worked remarkably well. But to be competitive in Group B, we needed an engine that produced in the region of 400bhp. David Wood and his team certainly delivered on this.”

Bespoke

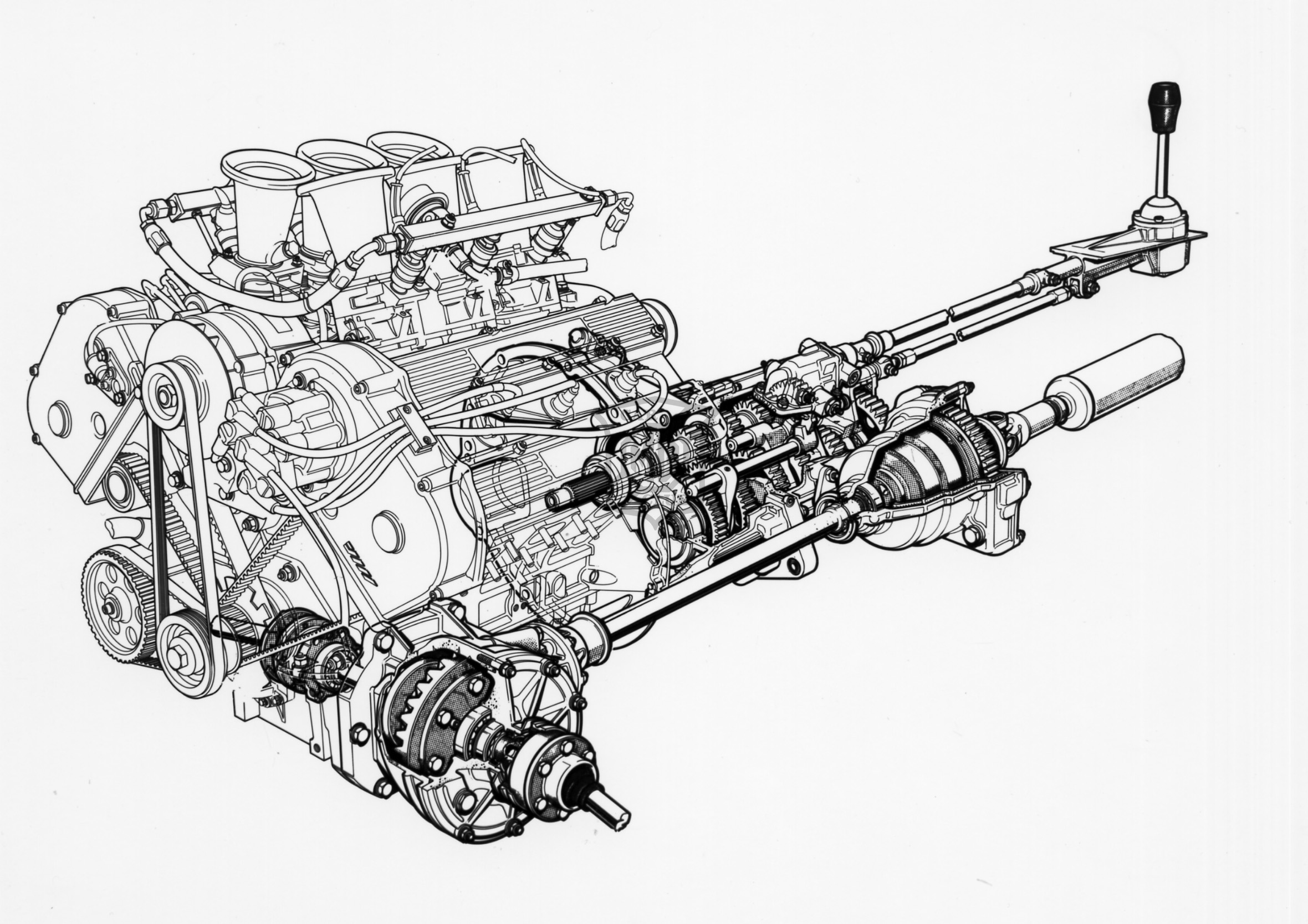

“The V62V had enough power, and was designed to mate perfectly to the 6R4’s transmission,” explains Wood. “This meant that the motorsport team was able to test the car, its transmission, and packaging, in an effective manner. But, to compete at WRC level, at least 400bhp was needed. The management board analysed the plans I submitted for a new V6, quad camshaft, 90-degree, four-valve-per-cylinder ‘V64V’ engine and approved it. We had a lot of support from Harold Musgrove.

“However, time was of the essence, and there were budget constraints too, so the basic dimensions of the Rover V8 engine were utilised, with the patterning being altered to make them suitable for a V6. Mahle produced the pistons, G&S the valves and Gordon Allen made the crankshaft and rods to our design. The heads, designed in-house by Bob Farley and his small team at Canley, were cast and machined by Cosworth. The valve and throat angles were similar to a Cosworth DFV.

“The engine was produced in two guises. International engines had double valve springs, very high-lift camshafts, six throttle bodies and ultimately produced around 410bhp. Clubman engines, which were rev-limited to 7,000rpm and delivered 250bhp, had Rover V8 conrods (but produced in stronger EN24 steel), single valve springs and a simpler inlet manifold and plenum complete with a single 52mm butterfly from the Rover Vitesse.”

Drive

If the engine was a crucial element in the 6R4’s WRC/Group B and national rally makeup, then so too was the transmission system. John Piper elaborates. “There was a main gearbox, more or less central in the car, ahead of which was a step-off unit that also housed a Ferguson Formula viscous-coupling centre differential. Running forward to a front diff, designed by Bob Farley, was a jointed propshaft from the step-off unit. The rear drive was carried through a quill shaft along the right-hand side of the sump and into a rear differential unit cast integral with the engine sump, under No. two main bearing cap, but with its own oil supply. The rear diff and sump were also Bob’s handiwork.

“I designed the gearbox casing and the step-off unit integration, with help from Mike Endean on the gearbox internals. Mike worked for Hewland at the time and was contracted in. Although complex, the transmission system was robust and relatively easy to work on. Plus, depending on the nature of the event, the torque-split could be altered.”

Part two on the success and frustrations of the MG 6R4 will be available to read soon.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club