Reproduction in whole or in part of any article published on this website is prohibited without written permission of The MG Car Club.

“That’s standard, sir!”

By Mike Allison

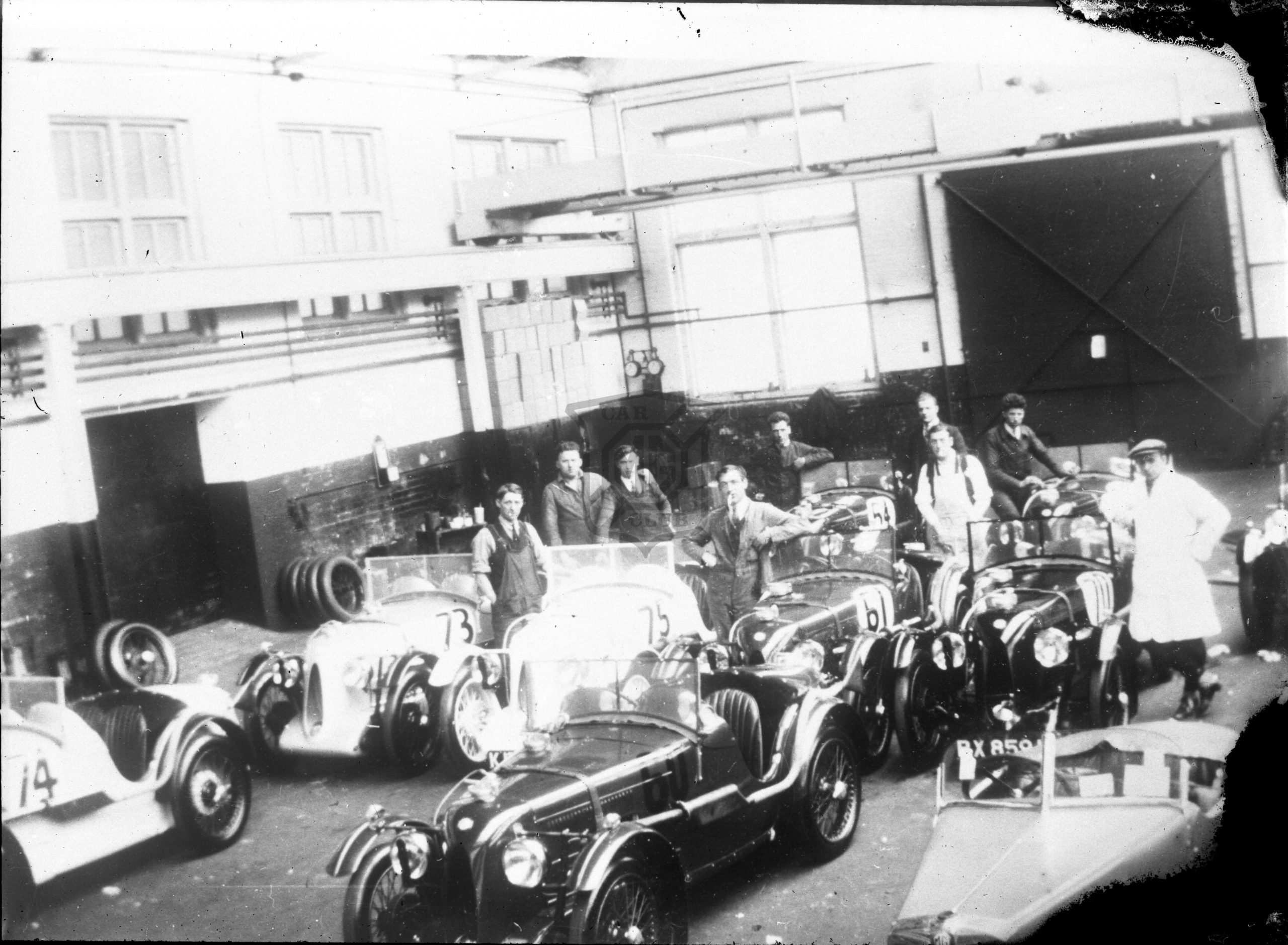

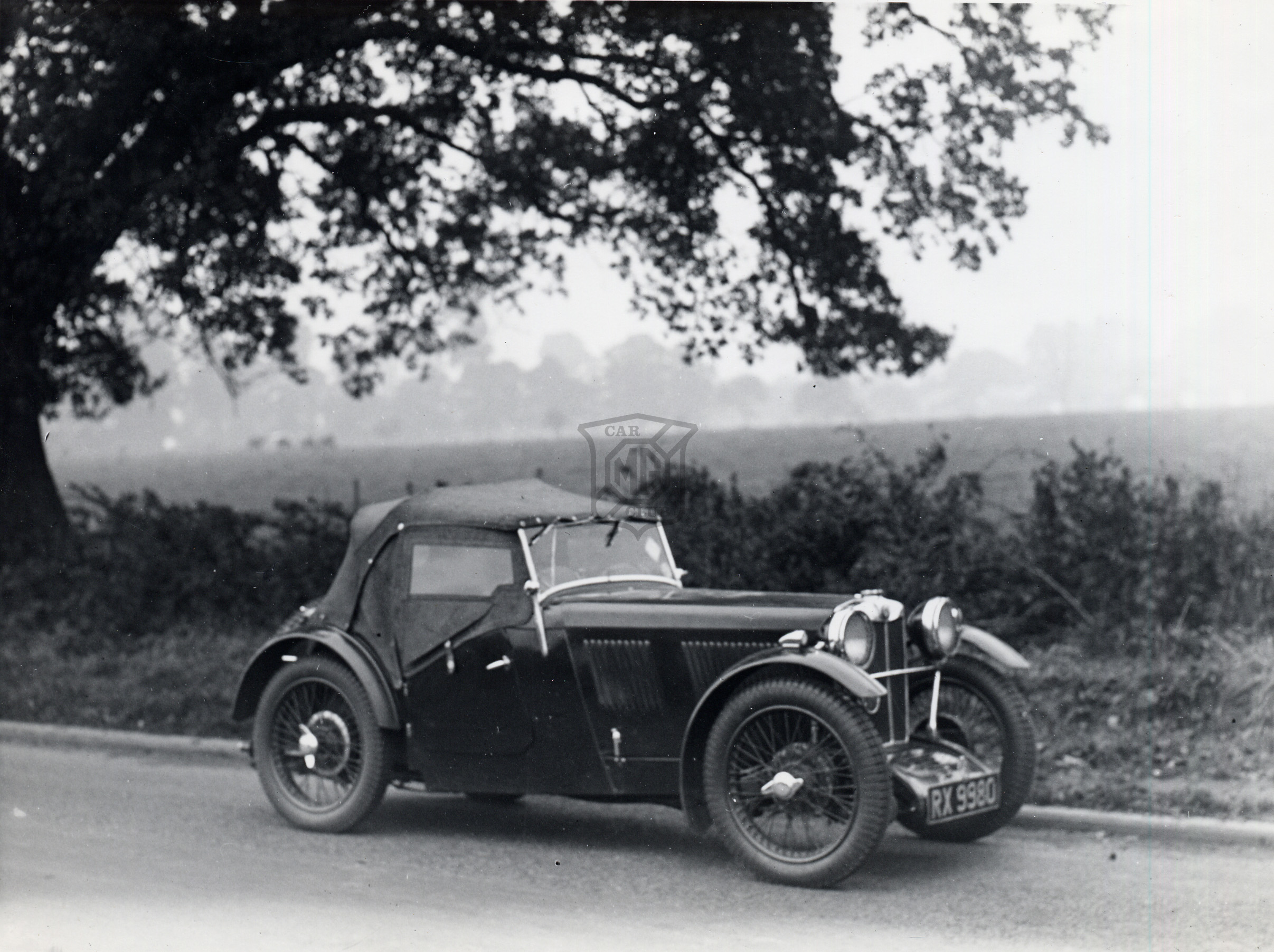

When buying a new car now, and there is a minor niggle, one automatically thinks that the car manufacturer should fix the problem on a free of charge basis. The first response you will get from the dealer is “Oh, yes! That’s standard for this model!” We all tend to think of our old MG cars as wonderful, and, don’t get me wrong, they are! However, have you ever wondered what it was like when, in 1930-something, you took delivery of a brand new shiny M, D, F, J, K, L, P or N, which we now so revere?

Received information, with which we have lived for many years, is that the cars were noisy, leaked oil, and were generally mechanically troublesome from new: as a driver you were constantly in fear of being at the mercy of a garage mechanic, and the fact that he probably would cause more harm than good. This view was compounded by the older factory people who believed that each year’s products were better than the previous models. By the time I worked at the Factory, even the MGA was considered a troublesome car, and not nearly as good as the MGB! I had not really considered the subject analytically, until I started my project to record the Service Department reports of all Triple-M cars.

Not all these details for every car exist some because some of the cars were exported, never to be heard of again, and a small number because the cars were fitted with special bodies and these were not subject to service at the MG Car Co Ltd. Some of the records have just got lost over the years. In general the dealers were expected to deal with the customer, but there was always a lively exchange of correspondence when the Factory was expected to underwrite work carried out on their behalf. Those cars that were serviced came with a variety of complaints, which owners expected to be put right by the Factory, and one cannot argue with this view. However, some of the reports are not those I personally would have expected, from what I had been led to believe!

So, we have become conditioned to believe that MGs of the early to mid-30s were inherently unreliable; however we cannot really judge with hindsight what the original owners thought of their cars. We have to accept that the motor car as a vehicle was still barely 50 years old in 1930, and the cheaper cars were attracting customers who were not necessarily familiar with what to expect. In short, overall standards were lower than those we have come to accept in the 21st century.

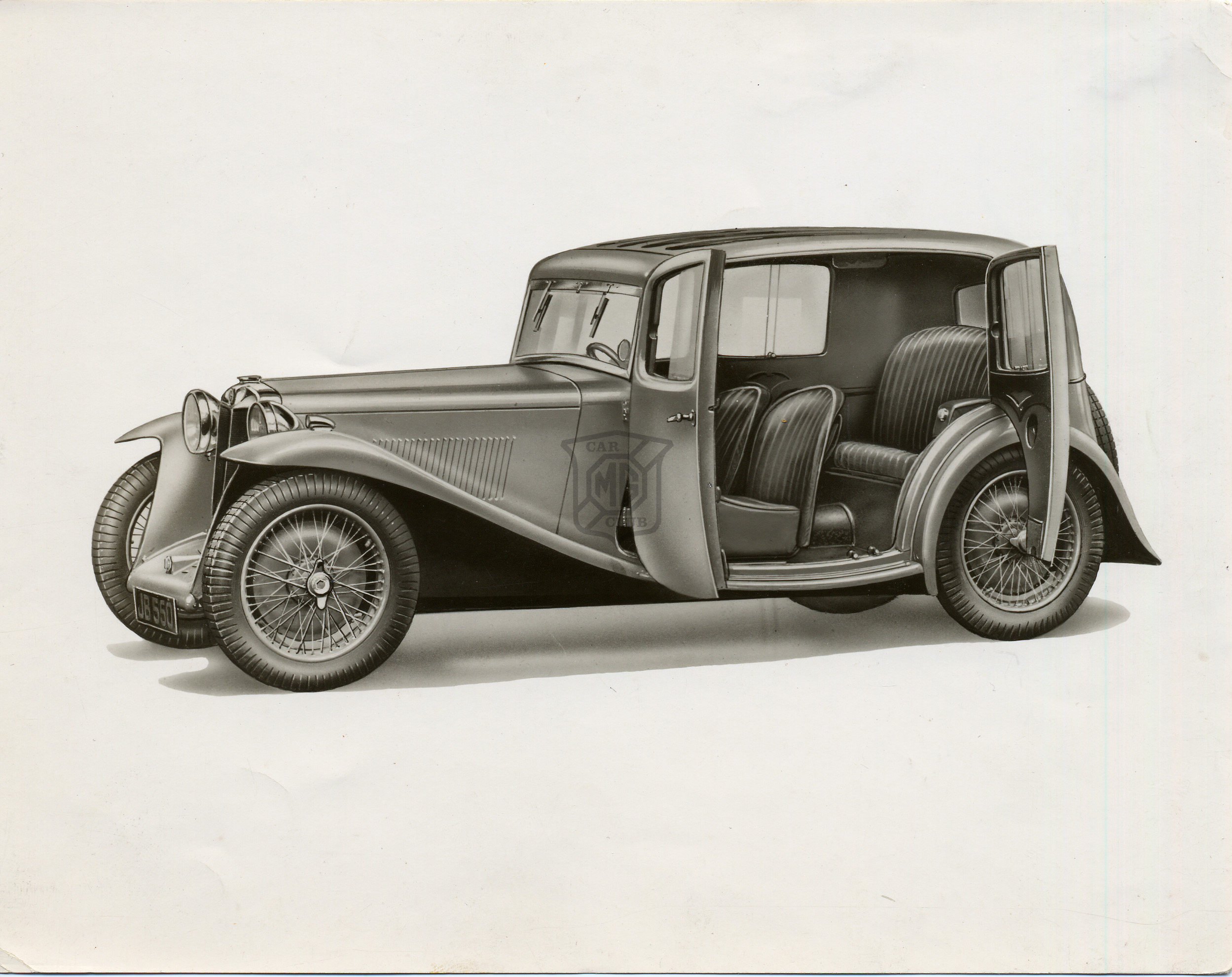

It came as a surprise to me that in fact the cars were not judged to be unreliable. By far and away the largest number of complaints were not of the mechanical defects, but body-related. There were problems with doors flying open, body parts breaking or even falling off, windscreen breakages, paint defects, and complaints related to poor plating of bright parts. The saloon models had many complaints, but lack of internal water-proofing was common, and seldom were such complaints treated kindly. This I found genuinely surprising: the cars were said, when I was young in the late 50s, to have been unreliable, leaking oil, noisy in the transmission and poor on engine oil consumption… no mention of body defects at all, and this may have contributed to Alec Hounslow saying to me once that “… the bodywork only covers the important bits, and generally makes them inaccessible!”

There were very few reports of oil-filled dynamos, although several of non-charging units, usually rectified by the supplier. About the only fault that has come through in unbridled truth is the high number of broken crankshafts on J2s (around a 20% incidence) and rear axles of all models (about 4%). All other faults can hardly be called ‘common’ or of high incidence, as we reported in my days of Quality Control in the 60s and 70s. In fact, warranty claims were not common. I would estimate the overall incidence at less than 5%, so for the vast majority of owners the cars must have represented good value, as well as being reliable in service. However, then as now, those who had trouble made a loud noise about it. I remember saying in a meeting more than once that even a 0.05% incidence is important, because for the owner, it represents a 100% incidence! Some people became anti-MG as a results of their experiences, but this probably only amounts to 10, out of a sales record of 11,000!

One has to remember, however, that service routines were fairly far reaching, requiring the chassis to be oiled before each journey, a weekly service of greasing and oiling, coupled with a recommendation for decarbonising every 3,000 miles, or once every other engine oil change!

So, what problems did owners complain about, and how were they dealt with? I will not be covering the problems blow by blow, but will attempt to give a broad overall picture of what the cars were like in the eyes of the first buyers. Although we would now be tempted to think of cars as ‘cheap’, in reality they were not particularly so, costing around 50% more than a similar sized everyman’s transport car. It was a case of the small sports car (Midget) costing around £220, the same as a medium sized saloon, such as a Morris Twelve, or the Magnette costing roughly £300, as much as large one, such as a Morris Isis. In the early 30s, £25 was a substantial sum of money, with most working people earning perhaps £50 a year, and a bank manager perhaps £200 a year. Regarding the cost of the car, you could buy five MG Magnettes for the cost of a Type 43 Bugatti chassis, or seven for the cost of a Bentley saloon! Amongst closer competitors, the MG Magna was cheaper than any Riley, while the only straight price for price competitor was the Singer Nine Sports.

So who bought them? As sports cars the cars were bought first and foremost by those who wanted to drive for fun. However, the cars were attractive to look at, and so also appealed to those who wanted to ‘cut a dash’, as the contemporary saying had it, or would impress the ‘Jones’s’ as we might now say. Quite a few young ladies bought MGs in the newly liberated society of the first third of the century. Quite a few were bought as second cars ‘for the wife’, or more likely the illicit lady-friend! Then a large number of doctors, servicemen and clergymen bought them. Titled gentry bought a few MGs, and so did those now referred to as ‘celebrities’, actors and the like. Many rich young men bought MGs, and not a few of these were third year students at Oxford and Cambridge. Not surprisingly, quite a few of the cars were used for motor sports events, mainly trials, although quite a few cars were rallied seriously, and even raced in low-key Brooklands ARC meetings and similar events.

What specific warranty problems were reported, and claimed? As intimated above, body issues were the commonest problems, starting with the M-type. The tendency for doors to fly open was common, and was usually dealt with by the agents selling the cars. Claims for a few pence were settled without question, but the larger the claim, the more the argument with the dealer! With the D and F types, particularly tourers, started the claims for broken windscreens, which the Company refused to accept, saying that “… all glass was expressly excluded from the terms of the guarantee.” Poor paintwork was another persistent claim refused by the Company except in a small number of cases where customers got extremely annoyed!

Probably the most common mechanical complaint was that the car lacked power. Tactful letters to owners were sent, explaining that “free use of the gears was to be expected with a car of modest power”. The saloon Magnettes were the source of relatively large numbers of complaints, one customer retorting that if he was expected to drive the car in such a manner, he would expect it to be quieter! Noise levels were not often complained about, although gearboxes got their fair share of complaints. Replies to dealers were along the lines of the gearboxes are inherently noisy, but should be silent in top gear!

Customers complained that they could not reach press speeds in their cars, but often a road test negated these claims, and the customer was sent away apparently satisfied. I believe that quite a few customers were treated to a demonstration drive by one of the testers, and Fred Kindell was mentioned in this connection to me by more than one of his pre-war colleagues. The standard for each model was 60+ for M and D-types, and 70+ for F-types. With the J, 70+ was set as a standard, which was repeated throughout the P-type range. K-types had an expected road test standard of 70+, with L-types 75+ and N-types fastest of all, and expected to reach a minimum 80mph. These figures are all quoted from actual Factory testers’ runs. Cars not reaching the standard were sent for an ‘outside tune’, after which they almost invariably reached the required standard. All of this can be put in context when it is remembered that the Morris Twelve or Morris Isis, mentioned above, had a top speed of 60/65!

Excessive oil consumption was most definitely a problem complained of, and when the car was not too old (less than nine months) these were listened to sympathetically. The engine might receive a new set of pistons, and in some cases a complete replacement engine. With the J-type cars, the problem was often compounded by crankshaft failure. Nearly all claims were met with a replacement crank free, although the customer had to pay for stripping and rebuilding the engine, often at “a special price of £15”. By the time the cars were two or three years old, crankshafts were supplied at 50% of list price (which was less than £5!). Interestingly, the quoted ‘acceptable’ oil consumption was reckoned to be 1,200 miles per gallon, or 150 miles to the pint! A ‘reasonable life of the engine before a rebore is necessary’ is quoted in one letter to a P-type customer as being 30,000 miles, which is probably a criticism more of the quality of oil than then engine, so again we see a change in standards.

Fuel consumption was not much of a bone of contention, and the quoted figures by Service Department of 30–32mpg for the Midgets, and 22–25 for the six cylinder cars… much what we expect nowadays! However, with modern technology we would expect at least twice the economies of a car with engines of 850–1286cc, but not many cars are now made with such small engines!

Braking performance was seldom criticised, we may now be surprised to hear. Users of the cars now nearly all complain about poor brakes, but like the car performance it is a reflection of driving style rather than of the car itself. The reason for this was that drivers did not rely on their brakes except for emergencies; one was taught to use the gearbox and engine compression to slow the car on the road… even when I learned to drive in the 50s, this was the way driving schools taught. It was considered an art to drive from place to place without using the brakes. Testers regularly commented on poor brakes when driving the cars, even though customers had made no complaint! Brake adjustment was carried out for five shillings (25p).

Charges to our eyes were pretty small. An engine change was priced at £14, plus parts of course. The list price for an engine for a Midget was £30, and a Magnette £45 as an exchange part. A full service was carried out for 1/6d, plus oils and parts used, 7.5p in today’s money. Labour was charged out at 1/6d per hour in the Service Department. They paid 3d per hour to the mechanics, with overtime at 4d if required, plus 6d per hour to his supervisor, whose pay was based on a 48 hour week, with no overtime payments, a flat £2.14.6d. There were usually four or five mechanics in Service, and it was considered one of the ‘plum’ jobs in the Factory. All the men were expected to work a 48-hour week as a norm, with overtime as determined by the foreman. I was never cheeky enough to ask what John Thornley earned pre-war as Service Manager.

All of this is not saying the cars were trouble-free, merely that the problems were solved, and sometimes led to improvements in the cars by the Factory during production, and recommended service ‘fix-it’ information which was distributed to all recognised dealers. Every MG really was better than its predecessor! Warranty did cost the Company a significant sum of money, but some of the stories did get blown out of proportion to the number of actual complaints, but then, most customers buy a car and run it, and their experiences colour their view of the car, while the way in which they are handled by the dealers and manufacturer can result in no further sales to that customer. In the case of MG, many of the customers were obviously happy because they often bought a later model to replace their previous car, so not everyone was unhappy.

MG Car Club

MG Car Club